Bhaavna Arora’s Insight Into Kashmir Through Its Warrior Martyr Lt Ummer Fayaz

Lt Ummer Fayaz lived a short but eventful life. It is important to convince the Kashmiris that there could be many more like him who would want to see a positive change.

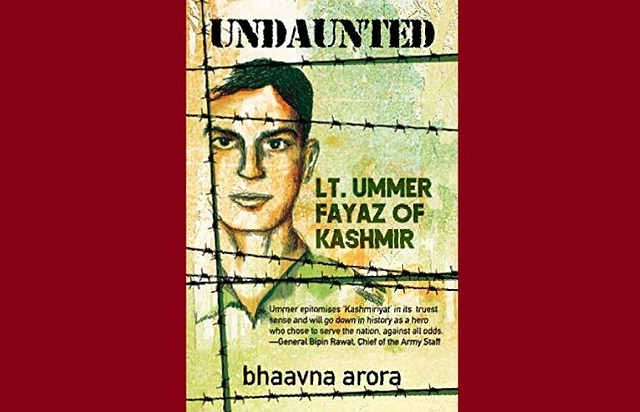

Bhaavna Arora. Undaunted: Lt. Ummer Fayaz of Kashmir. Westland Books. 2019. Rs 196. PP 232.

Just a little under two years ago, author Bhaavna Arora came calling on me and spoke of her intent to write a book on late Lieutenant Ummer Fayaz, the young army officer from Kulgam in Kashmir, who was killed on 10 May 2017 by terrorists while on leave. Arora was all fired up but had little knowledge of the ground swell in Kashmir’s dangerous war zone. In March 2019, I had the honour and pleasure to be a part of the panel which discussed Arora’s promised book, and released it at a very appropriate ceremony at the Rajputana Rifles Regimental Centre in Delhi.

In less than two years, Arora had managed to get the permission of the army, conducted field visits to Kashmir and to the location of Lt Fayaz’s unit near Akhnur, spoken to umpteen relatives and friends of the young officer in different military institutions at Mhow, Deolali and Pune, and written a highly factual and emotional book.

Much credit must go to her for that. Many may perceive it to be just a biographical sketch of the martyred officer. However, I may strongly recommend, right at the outset, that this is a book which actually explains many unexplained aspects of the social environment of Kashmir. Books on the strategic and political aspects are numerous but a book with a humane look at the social environment is a rarity.

Lt Fayaz, a young Kashmiri lad, the brave heart who had the courage to join the Indian Army through the National Defence Academy (NDA) despite the prevailing anti-national sentiment and alienation in Kashmir, was commissioned into 2nd Battalion the Rajputana Rifles, one of the finest, courageous and well known units of the Indian Army, in December 2016. This regiment is known for its iconic operations leading to the capture of Tololing during the Kargil War 1999. It served under my command in 2011 at the challenging location of Lachchipura, near Uri.

Having served in the Akhnur sector for just four months with his unit, Lt Fayaz returned home for a brief spell of leave for a family wedding. During the event, his presence was noticed by terrorists, who isolated and kidnapped him before brutally killing him. As Arora explains later threats were probably in existence even when he was a cadet at NDA and had to avoid home visits during various term breaks. The entire nation was shocked by the brutality of the act and pointed targeting of someone who had clearly rejected the idea of picking up weapons against the state in favour of joining the army to look at ways by which he could promote peace.

Arora took it upon herself to investigate not only Lt Fayaz's life but also the prevailing social, political and security environment in Kashmir which conspired to take the officer’s life. She took some advice from me and other experienced hands to undertake the risky journey of venturing into Kashmir's conflict zone. But the kind of energy she displayed in reaching out to members of the extended family, classmates, sweetheart, policemen and very importantly the Commanding Officers (COs) of the Rashtriya Rifles (RR) units in the area where he studied and his hometown in Kulgam, was indeed remarkable.

I always maintain that if the ground swell is known to anyone in Kashmir it is the COs and police officials such as Ashiq Tak, who is often mentioned in the book. She travelled mostly under army arrangements with local Kashmiri soldiers accompanying her in civilian vehicles, something that is always risky on Kashmir’s unpredictable roads; single man protection hardly being a guarantee. She has recorded many of those conversations with taxi drivers and Kashmiri soldiers in different segments of the book, all remarkable revelations of the ground situation and perception.

The narrative is quick and fast flowing with a little bit of back and forth but just the right amount, enabling the reader to keep the connect. The most relevant question on anyone’s mind should be why Lt Fayaz chose to become an army officer. Arora struggles with attempting to get the answers out of people she met and the uninformed reader may never be able to gauge why it happened at all. The classmates and all others are adamant that he was wrong in choosing to join the army but those who knew him intimately spoke of his anger at the treatment meted out to Kashmiris but yet cautioning those who wished to pick up the gun.

Arora does reveal twice that Lt Fayaz was influenced by my presence at Srinagar, in 2010-12 and wanted to adopt my style of convincing people about the wrong they did. It is touching to see how he was influenced by the Kashmir Premier League cricket tournament instituted by the army during my command tenure. He is known to have stated that he preferred to see more youth to be in possession of cricket bats in their hands rather than firearms.

He chose to keep secret his intent of joining the NDA and later through this time (three years at NDA and one at Indian Military Academy, Dehradun) his cadet years did not draw too much negative attention within Kashmir, although he had to desist from travelling home during term breaks. The book obviously being all about Lt Fayaz and his passion to do something different to overcome the humiliation of the Kashmiri people that he perceived focuses much on his character.

Importantly, he is not painted a hero except the fact that in his student days he stood out distinctively as someone who was capable and different. Arora’s emphasis on his family is appropriate because without this insight the sheer courage of some Kashmiri families gets neglected. The family did not stop him from filling his forms for NDA which they could easily have done through emotional blackmailing. This is the tragedy of Kashmir.

The army is one of the few institutions which understood the predicament of the Kashmiris very early. Its commanders went beyond the call of duty to do a lot for the populace but that yet proves to be insufficient in the absence of a national effort to do the same. Each of the COs Arora met during her journey through Kashmir had sufficient pearls of wisdom to share with her.

Among the reasons for alienation which get identified in the narrative are behaviour by policemen at checkpoints and the treatment meted out during cordon and searches. Much of it is actually hearsay and the negative word has a way of spreading far and wide. The positives are rarely discussed by the populace. The frequent free medical camps, which are otherwise so popular, the daily clinics run by so many RR units and the great work done by the army in contributing towards education through the Goodwill Schools all remain unappreciated by those who receive the benefit from them.

In addition, hundreds of computer centres set up to impart computer training never get mentioned. The media covers all this perfunctorily with news stories; it never finds mention in commentaries. The relationship enjoyed by the army with the border population remains completely positive; this too rarely finds mention in any discourse in Kashmir. The fact that in winter when everything closes down and services meant to be provided by the civil administration remain paralysed it’s only the army to the rescue, even evacuating women in the family way from hamlets in high altitude terrain.

To casual visitors none will ever acknowledge or would even be aware enough that the entire Kashmir education system was callous enough never to have catered for toilets for the girl child. None but the army came forward to take the lead in the construction of these. The role that the army has played and continues to play in the social environment of Kashmir remains insufficiently appreciated.

Lt Fayaz’s targeting by terrorists was something inevitable. He symbolised the rationalist among the youth; he would not take literally anything in the radical talk by disaffected youth and clerics. The terrorists too realise that they walk a thin line. The thousands of young Kashmiris who throng recruitment centres of various security organisations may be doing so for the sake of a job but the fortunate few who get selected invariably have a change in thinking once they are in contact with people from other faiths and regions of India.

It is for this reason that terrorists commenced the targeting of local servicemen and police personnel, finding them easy targets for a campaign they hoped would discourage the youth to look towards the security forces as institutions to pursue a career with.

Undoubtedly, one of the highlights of the book is the description of Lt Fayaz’s years at training at the NDA. This reveals just how secular and pluralistic are institutions in India, unaffected by any attempts to change this from our national character. The way in which NDA caters to the requirements of Muslim cadets for fasting during Ramzan should itself project sufficiently to Kashmiris the degree of sensitivity which the armed forces exercise in dealing with them.

To her credit, Arora chooses to highlight many of these snippets of life at the academy including the knowledge of squadron commanders about the necessity of Muslims to undertake all normal activity even while fasting. The fact that that Fayaz could spend a few days with the family of his squadron commander when he was unable to go home due to the prevailing threat, reveals even higher level of understanding among officers of the services; kudos to them.

The comparison of Lt Fayaz with Burhan Wani; Arora again does this creditably giving Lt Fayaz all his due for his broad vision and ability to discern the necessity of understanding and continuing engagement. But she reserves the best for the near end and the finale of the book. Including in the book the oath of the Indian Army officer, taken by all officers commissioned from IMA, Dehradun gives the opportunity to the reader to appreciate how a single segment of India gives up everything for the sake of the nation, including subordinating one’s life for the national cause. Most people have little idea that no other organisation in the nation does this; the armed forces officer is the only one who willingly gives up his fundamental rights, including right to life for the sake of his nation.

The last chapter covering Lt Fayaz’s death and the response is really the grand finale of the book. Just the right words, the appropriate description and the most sensible sentiments find their way into this chapter, which is kept at just the right length to leave a lasting impact on the mind of the reader. Lt Ummer Fayaz lived a short but eventful life. It is for us to convince the Kashmiris that there could be many more like him who could rise and deliver them to the positive destination they need to look forward to.

In my speech at the book launch I summed it up by stating — “Kashmir ki jeet tab hogi, jab har ghar se ek Ummer Fayaz nikalega” (Kashmir’s victory will be complete when from every house will emerge an Ummer Fayaz).