Swami Vivekananda: Resistance Icon Against Colonialism And Theo-Colonialism

Was Swami Vivekananda’s ‘Vedantic universalism’ truly inclusivist? This book tries to deconstruct the man, the Swami, and his philosophy in the context of the much-abused ‘political Hindutva’.

Stephen E Gregg, ‘Swami Vivekananda and Non-Hindu Traditions: A Universal Advaita’, Routledge, 2019 $134 (Kindle $57.99) pages 260.

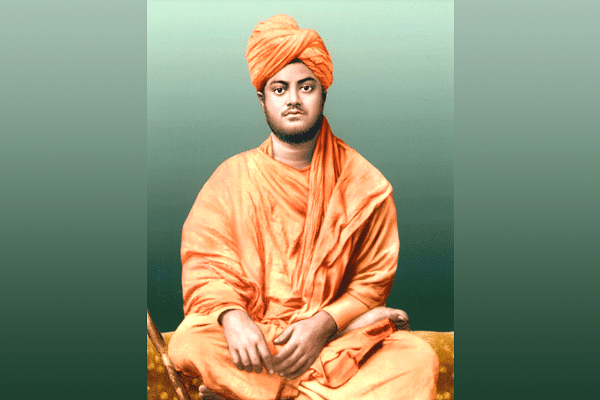

“Not this. Not in saffron. Can you please find a photo of Swami Vivekananda in white?”

I remember this question that became an inside joke in Kanyakumari Vivekananda Kendra circles in 1993. The Human Resource Ministry of the Government of India was organising an event at Kanyakumari to commemorate the centenary of the ‘Chicago Address’ of Swami Vivekananda at the World Parliament of Religions.

As then minister Arjun Singh was allergic to saffron, the officials were in a hurry to get a photo of Swami Vivekananda to adorn the dais but without getting blamed for any saffronization. Those days, Photoshop was not around in printing presses and hence the desperation.

From the days of direct colonialism of the British day to the indirect colonialism of the Nehruvian era, colonial forces of both the empire and the mind, have always found a formidable enemy in Swami Vivekananda.

British Intelligence followed him closely and he figured in their intelligence reports even before he became famous and even after he died.

Simultaneously, there was an attempt to differentiate ‘the spiritual’ Swami Vivekananda from the ‘political’ national liberation movement.

As early as 1892, Calcutta Commissioner of Police had observed about Swami Vivekananda: ‘His real name was not known’. The same year, yet another IB report from Bombay found him ‘to be very clever, and, though a Sannyasi, to take an interest in politics.’

It is of interest to note that these reports on Swami Vivekananda were filed in the ‘Thagi and Dakaiti Department’.

The 1896 report on Swami Vivekananda notes that one of his disciples, Leon Sandsbury (Swami Kripananda), was ‘a Russian Jew …owning a pair of eyes in which the fire of the true fanatic burns.’

In 1918, the Sedition Committee report went in detail about the influence of Swami Vivekananda among Hindus and noted that he had advocated that Indians ‘must seek freedom by the aid of the Mother of Strength (Shakti).’

It then accused Barindra, the brother of Sri Aurobindo, for ‘perverting’ the influence ‘in order to create an atmosphere suitable for the execution of their projects’.

A 101 years after the British colonial administration accused Indian National movement of ‘perverting’ Swami Vivekananda, Dr Stephen E. Gregg, a Senior Lecturer in Religious Studies at the University of Wolverhampton, and the Hon. Secretary of the British Association for the Study of Religions, in his latest book on Swami Vivekananda (Swami Vivekananda and Non-Hindu Traditions: a Universal Advaita', Routledge, 2019) is at his scholarly best to prove that Vivekananda has to be 'best understood’ within the context of ‘Advaitic primacy’ rather than ‘Hindu chauvinism’.

Approvingly citing another establishment scholar of Western Hindu-studies brigade, he writes:

Highlighting the RSS’s desire to promote what they understand to be the ‘revivalist’ message of Vivekananda’s teachings, Beckerlegge suggests that this is best understood by separating the desired goals of Golwalkar 21 and Vivekananda as, respectively, positions of ‘exclusivism’ and ‘inclusivism’ towards Islam and Christianity; indeed Beckerlegge notes that “RSS writers ignore the positive comments that Vivekananda frequently made about Islam, and specifically about its social cohesion” highlighting the “carefully tailored selectivity of the RSS’s borrowing from Vivekananda.p.5

Despite the agenda, one redeeming feature of the book is its scholarship. So, ultimately, when the prejudices against Hindutva are set aside, it actually ends up validating Hindutva as the continuation of the legacy of the inclusiveness of Swami Vivekananda along with his framework for religious pluralism — rather than Hindutva ‘appropriating’ Vivekananda.

An interesting part of the book is the chapter where he discusses the religious milieu of Bengal through its historical context.

In this through the authority Prof. Eaton, whom anti-Hindutva factions love quoting with respect to negation of temple destruction, Gregg considers the ‘religion of social liberation theory’ of Islamization. He says:

It is ‘perhaps the widest held theory of the Islamisation of India...based on the premise that the Islamic conception of the umma (‘brotherhood’) was an attractive alternative to the hierarchical Hindu caste system, offering instead a social and religious sense of equality to the downtrodden or oppressed.

He points out that 'many Pakistani and Bangladeshi nationals, and . . . countless journalists and historians of South Asia, especially Muslims have subscribed to this theory and even Vivekananda himself alluded to this. But this is problematic.

Eaton notes that “premodern Muslim intellectuals did not stress their religion’s ideal of social equality as opposed to Hindu inequality, but rather Islamic monotheism as opposed to Hindu polytheism.” Also, no evidence exists to suggest that Muslim converts benefited in social status — indeed, most simply carried into Muslim society the same birth-ascribed rank that they had formerly known in Hindu society.p.38

Further in his discussion of the immediate socio-religious situation in India, particularly with respect to Christian missionaries, Gregg points out that even a person initially sympathetic to Christian missionaries like Keshab Sen would later become a critic of missionary enterprise pointing out that 'the sum annually spent on mission is £250,000' which Gregg estimates would be 'equivalent today to £148 million'.

Sen lamented about the missionaries thus:

Alas! Instead of mutual good feeling and brotherly intercourse, we find the bitterest rancour and hatred, and a ceaseless exchange of reviling, vituperation, and slander...(p.61)

Dr. Gregg finds very similar continuation in the consistent opposition Swami Vivekananda shows in his lectures against missionary activities. He also explains why, quoting appropriate passages from Vivekananda:

Vivekananda is clearly at odds, throughout his works, with the Christian concept of missionary activity to bring about conversion. ... Vivekananda believed that practical support and help from adherents of any religion to the needy of another religion was the only role of a missionary; indeed, he praises such work on several occasions. Vivekananda’s distaste for conversion derives from his conviction that people should mature and grow within their own religion, rather than attempt to embrace another tradition.p.163

In his approach to missionary activities again, Swami Vivekananda looks at three spreading religions namely, Buddhism, Christianity and Islam, of which he dissociates Buddhism from the way Christianity and Islam spread. He is appreciative of Buddhist missionary activity while damning both Christianity and Islam.

Gregg quotes particularly some very critical words of Swami Vivekananda in analysing the reason for the violent fanaticism of Islamic expansionism:

Whenever a prophet got into a superconscious state . . . he brought away from it not only some truths, but some fanaticism also, some superstition which injured the world as much as the greatness of the teaching helped.

Then Gregg adds a mildly insulting sharp remark:

It is interesting to note that Vivekananda does not seem to apply this logic to his own prophet, Ramakrishna.(p.167)

That is a pathetically misplaced criticism. The passage itself is part of the chapter 'Dhyana and Samadhi' in the celebrated book 'Raja Yoga'.

Here, Vivekananda makes no distinction. A look at the passage as a whole one can clearly find that he also includes such experiences from the Indian context as well:

So this explains why an inspiration, or transcendental knowledge, may be the same in different countries, but in one country, it will seem to come through an angel, and in another through a Deva, and in a third through God. … So we see this danger by studying the lives of great teachers like Mohammed and others. Yet we find, at the same time, that they were all inspired. Whenever a prophet got into the superconscious state by heightening his emotional nature, he brought away from it not only some truths, but some fanaticism also, some superstition which injured the world as much as the greatness of the teaching helped. To get any reason out of the mass of incongruity we call human life, we have to transcend our reason, but we must do it scientifically, slowly, by regular practice, and we must cast off all superstition. We must take up the study of the superconscious state just as any other science.

As any biography of Sri Ramakrishna shows, hagiography or not, shows Sri Ramakrishna went exactly through various spiritual disciplines, constantly testing himself and validating his spiritual experiences through different paths.

Clearly, Dr. Gregg is wrong when he projects Swami Vivekananda as having a blind-spot for his own Guru. In reality, this remarkable chapter in itself can be considered as a premonition of recent neurobiological researches into religious experiences.

In the end, Gregg considers ‘reformulation of Hinduism’ by Swami Vivekananda as having three aspects: hierarchical, inclusivistic and universalistic.

Hierarchial, because according Gregg, Vivekananda considers ‘Gauni Bhakti’ as ‘the lowest stage’ of spiritual development and ‘inclusivistic’ because he acknowledges 'the value of Gauni Bhakti as a preparatory, and indeed necessary, step towards higher spiritual truths' and sees this movement from Gauni Bhakti to non-dual realisation as a universal phenomenon. (p.226)

With such analysis, Gregg triumphantly announces the conclusion:

This work has, therefore, demonstrated that a close reading of Vivekananda’s comments upon non-Hindu traditions, in relation to his framework of Hinduism challenges the notion that Vivekananda’s teachings could be understood to underpin right-wing Hindutva ideologies … If Advaita is beyond sectarianism, Vivekananda’s mission could not be said to support right-wing politics of any sort, and those that appropriate him for such a cause are guilty of a misappropriation.

But what does the book really demonstrate?

We find the same discourse even further elaborated and practically taken up by manifest-Hindutva ideologues and organisations. Let us consider ‘Veer’ Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

In his very treatise on Hindutva, the discourse culminates in the above mentioned aspect of Advaita applied quite forcibly to a discourse on defining national character:

... A Hindu is most intensely so, when he ceases to be a Hindu; and with a Kabir claims the whole earth for a Benares ... or with a Tukaram exclaims: ‘My country? Oh brothers, the limits of the Universe — there the frontiers of my country lie.”(Note: In many editions in the place of Kabir one finds Sankara)

Veer Savarkar also resonates with Swami Vivekananda’s concept of Samadhi and its universal nature in designing the flag of Hindu Mahasabha takes what Gregg describes as the ‘hierarchical, inclusivisitic and universalistic’ framework:

Hindus have perfected a science based on experiment which can be termed as the highest blessing on human life. This Shastra is called the Yoga. ... The Symbol is that of the Kundalini. It is not the characteristic of any particular Jati or Varna. It exists in all human beings. ...To acquire this supreme joy or bliss is the highest ideal of man, be he a Hindu or a non-Hindu (Muslim, Christian or Jew), i.e., believer or non-believer, citizen or forester. This Yogashastra is a science of personal experience. Therefore, the Kundalini which is ...man’s highest progress and eternally blissful state of superconsciousness which can be personally experienced can alone be the symbol of the great ideal at which the Abhyudaya of the Hindu Nation aims.Vinayak Damodara Savarkar, ‘<i>Abhinava Hindu Dhwaja</i> (Hindu National Flag)‘

Here, we clearly see both inclusiveness and ‘universalism’ even while also emphasising the Hinduness.

Then, when one goes through the writings of ‘Guruji’ M S Golwalkar whom Dr. Gregg singles out as an example of Hindu chauvinism in his book through the above passage, one finds the same so-called ‘hierarchical inclusivist’ approach.

Even though Golwalkar, unlike Vivekananda and Sri Aurobindo, does not accept Jesus as Divine but he did not demean him as a false prophet or charlatan — something Christian missionaries indulge in ground-zero of the proselytizing battle that still happens in India.

Golwalkar considers Jesus a ‘great seer’. In his lectures, he could even cite the example of Jesus to underline positive attitude to service. For example, in ‘Bunch of Thought’, a collection of his speeches we find this:

We deem the offering made with real devotion as the noblest and highest, just as Jesus considered the old woman’s small coin a nobler offering than the treasures donated to the Temple by persons rolling in wealth.‘Bunch of Thoughts’, p.358

We also find that he makes a clear distinction between the missionary activities and the teachings of Jesus himself, a position strikingly similar to that of Vivekananda and later Gandhi:

Jesus had called upon his followers to give their all to the poor, the ignorant and the downtrodden. But what have his followers done in practice? Wherever they have gone, they have proved to be not ‘blood-givers’ but ‘bloodsuckers’? What is the fate of all those lands colonised by these so-called disciples of Christ? Wherever they have stepped, they have drenched those lands with the blood and tears of the natives and liquidated whole races. Do we not know the heart-rending stories of how they annihilated the natives in America, Australia and Africa? Why go so far? Are we not aware of the atrocious history of Christian missionaries in our own country, of how they carried sword and fire in Goa and elsewhere?pp.185-6

Golwalkar also echoes Swami Vivekananda’s views on missionaries. He says:

... our Buddhist monks and missionaries too who crossed the borders and reached distant lands in the initial stages were revered and their examples and teachings were set up as standards in all those countries. A disciple of Buddha had gone to Tibet, China and Japan. His idol was actually worshipped as God in these countries. How did this miracle happen ? It was the intense spirit of self-sacrifice and service, the all-embracing love, and the sheer merit of noble character of such missionaries that made them the cultural preceptors of those people and earned the name of Vishwa Guru — World Teacher — for our Bharat.p.38

Finally, and more crucially, he recognises the freedom of the individual to choose his or her own religious path and only emphasises that it should not cut the person off from the national life:

… we should make it clear that the non-Hindu who lives here has a rashtra dharma (national responsibility), a samaja dharma (duty to society), a kula dharma (duty to ancestors), and only in his vyakti dharma (personal faith) he can choose any path which satisfies his spiritual urge. If, even after fulfilling all those various duties in social life, anybody says that he has studied Quran Sharif or the Bible and that way of worship strikes a sympathetic chord in his heart, that he can pray better through that path of devotion, we have absolutely no objection. Thus, he has his choice in a portion of his individual life. For the rest, he must be one with the national current.p.133

The views of Swami Vivekananda and ‘Guruji’ Golwalkar are amazingly similar with respect to religious pluralism and inclusiveness.

For both of them, Islamic and Christian proselytizing activities are problematic and not the spiritual worth of the religions themselves.

Dr. Gregg, through a thorough study of Swami Vivekananda, comes to the conclusion that Vivekananda in his essence and spirit is not chauvinistic. But the very same aspects with which he comes to this conclusion are also found in the essence and spirit of Hindutva discourse.

So, the only credible conclusion he can come to is that Hindutva is the continuation of Vivekananda’s vision and mission and is inclusive and non-chauvinistic.

In India, the preservation of a mechanistic secularism has become only a preparatory stage for establishing a theocratic state by competing monopolistic religions namely Christianity, Islam and Marxism.

India offers to all these three conquering-mode theo-politicians an opportunity to establish a theocratic State with a theological control on the population that could only rival their medieval hold in Europe, in Saudi Arabia and Stalinist Russia or Maoist China.

Hinduism, with its liberal and inclusive nature, naturally becomes a target because often, it fosters an environment that blunts the visceral hatred needed for aggressive proselytizing.

Nehruvian polity, with its colonial anti-Hindu bias and inherent pro-Marxist leaning, provides a war-field and harvesting field for souls, which unfortunately uses the very liberal, spiritual democratic nature of Hinduness to work for the annihilation of Hindu Dharma. Hindutva movements then represent a resistance movement against these anti-democratic theo-colonial aggressions.

In this battle, Swami Vivekananda has, for the last 12 decades, emerged as the symbol of the explicit colonial resistance movement then and has re-emerged as the symbol of the resistance movement now.

So, just as how British colonialism wanted to see in the National Movement ‘perversion’ of Swami Vivekananda, today, the pro theo-colonial forces strive their level best to dissociate the formidable figure of Swami from Hindutva movement.

The book, despite the failed agenda, is a welcome and positive addition to the ever expanding literature of Sri Ramakrishna-Vivekananda studies.

Stepehen E Gregg, 'Swami Vivekananda and Non-Hindu Traditions: A Universal Advaita', Routledge, 2019 $134 (Kindle $57.99) pages 260