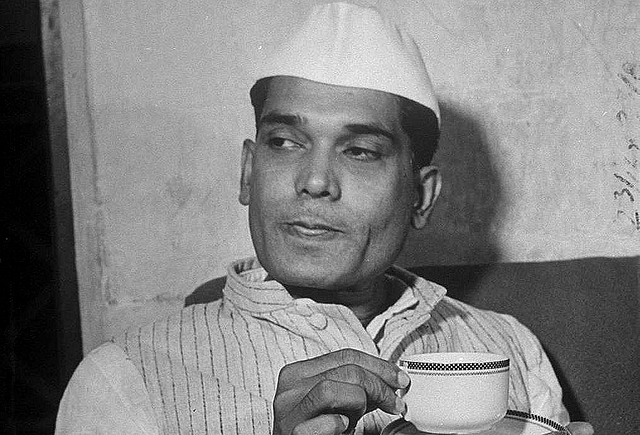

When Indira Gandhi Was More Scared Of Jayaprakash Narayan Dying Than Him Being Alive

An excerpt from the book ‘The Emergency: A Personal History’ by Coomi Kapoor looks at the deteriorating relationship between Indira Gandhi and Jayaprakash Narayan before and during the Emergency years.

The failure of Jayaprakash Narayan and Indira Gandhi to reach any understanding, despite the old and close association between JP and Mrs Gandhi’s family, was because of their widely differing perceptions.

To JP, his campaign was a mass movement against growing corruption in public life, and increasingly authoritarian tendencies in government at both the Centre and state levels, with frequent suppression of civil liberties.

JP believed that, far from creating an atmosphere of anarchy and violence, his movement provided a peaceful outlet for the anger and frustration of the youth, in particular of students. But instead of being responsive to their unrest, the government set about crushing the movement with a heavy, repressive hand. This was because Mrs Gandhi viewed JP’s movement as aimed personally at her.

She insisted that JP was encouraging anarchy, preventing the government from functioning, and trying, through a minority opposition, to submerge the voice of the majority. ‘Does he want to be a saint or a martyr? Why does he refuse to accept that he has never ceased to be a politician and desires to be the prime minister?’ she once complained to Pupul Jayakar. Historian Bipan Chandra described JP’s call for Total Revolution as ‘hazy, naïve and unrealistic thinking’ and his demands too general to amount to concrete politics.

Indira Gandhi’s dismissive opinion notwithstanding, JP was a formidable opponent, with a moral authority that Indira Gandhi lacked. He was an icon of the freedom struggle, a hero of the 1942 Quit India movement who had daringly escaped from Hazaribagh jail. When he was finally rearrested by the British he was released a full year after the other political prisoners.

Before he joined the freedom movement, JP had been a student in the USA for seven years and had impressed his teachers with his scholarship and keen mind. On his return to India, he was encouraged to join the Congress by Pandit Nehru. JP used to call Panditji ‘bhai’. The friendship extended to the two wives, Prabhavati and Kamala, who corresponded with each other regularly. It was a remarkably intimate exchange of letters between the two women.

After Independence, JP’s moral stature grew since he was one of the rare senior Congress leaders who had declined to accept political office. His revolutionary fervour had first taken him to Marxism and then, through the national freedom movement, to democratic socialism. When the socialists separated from the Congress in 1948 to form a separate party, he joined them. During that period, when JP was in the Praja Socialist Party, he was attracted to Vinoba Bhave’s Bhoodan movement, where donated land was collected for distributing to the landless.

By 1957, JP had resigned from party politics to devote all his time to the Sarvodaya movement, which practised social work based on the principles and values preached by Mahatma Gandhi. But, as JP noted in the Sarvodaya Sammelan of 1961, not being in any political party did not mean ‘we are not concerned about what is happening in the country in the political field’. He subsequently directed his energies towards trying to settle conflicts in Nagaland and Kashmir, and later in Bangladesh.

JP had a soft spot for Indira Gandhi as she was Nehru and Kamala’s daughter. He congratulated her warmly when she was elected PM in 1966. From time to time he supported some of the government’s programmes. In 1969, however, he was unhappy with her conduct in the presidential election. And he said so frankly in a letter to Mrs Gandhi in 1971, when he congratulated her on her sweeping electoral victory: ‘I did not like your conduct at the time of the presidential election though I am aware that at that time it was politically a question of life and death for you. Now that you have been given uncontested power my prayer to God is that he may keep your thinking pure.’

Cut to the quick, Mrs Gandhi wrote back haughtily, ‘How little do you know or understand me. I have never bothered about political or any other identity for myself. At that time, the question was not of my future but that of the Congress party and therefore of the country.’

During the Bangladesh crisis, relations between Mrs Gandhi and JP improved after he praised her role in the creation of Bangladesh. There were also cordial talks between the two on the surrender of dacoits in Madhya Pradesh and on the issue of capital punishment. However, things began to sour after JP expressed increasing disenchantment with the government’s style of functioning and the concentration of power in the hands of a single individual.

In early 1973 JP wrote to Mrs Gandhi, expressing concern about the elevation of Justice A.N. Ray as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court sidestepping three senior judges. He wondered whether the idea was to make the head of the Supreme Court ‘a creature of the government of the day’.

Later that year JP wrote to MPs, warning against the erosion of civil liberties and democratic institutions. He also raised the issue of corruption, and of electoral and educational reform. The PM did not take kindly to being lectured by JP. She started complaining that JP was confused and frustrated and wanted to grab power.

The relationship took a turn for the worse in March 1974 when agitating students in Bihar asked JP to lead their movement against corruption in the state. The Bihar Chhatra Sangharsh Samiti had drawn its inspiration from the youth of Gujarat, whose Navnirman movement with state-wide demonstrations, rallies and agitations had forced the corrupt Congress chief minister, Chimanbhai Patel, to step down in February 1974.

JP agreed to take up the students’ cause on the understanding that it would be non-violent and the movement would not be restricted to Bihar but would cover the whole country. He led a series of protests demanding the dissolution of the Bihar assembly.

In May 1974, Mrs Gandhi wrote to JP inquiring about his health. She added that in view of the long friendship between the two families, their political disagreements should not create personal bitterness or questioning of each other’s motives. Mrs Gandhi’s offer of peace would have seemed more genuine if she had not, just a short while earlier, at a speech in Bhubaneswar, made disparaging remarks about Sarvodaya leaders keeping the company of the rich and living in posh guest houses.

JP replied that the remark had deeply wounded him and he regretted that Mrs Gandhi failed to perceive the disillusionment of the country’s youth and the upsurge of support for his call for Total Revolution.

The PM, while claiming disingenuously that her remarks on Sarvodaya leaders did not refer to him in particular, refused to apologize. She asked him to consider carefully the company he was keeping in his movement, referring to the RSS and the Jana Sangh’s participation in his crusade. Both Nanaji Deshmukh of the Jana Sangh and Indian Express owner Ramnath Goenka were close friends of JP’s and the Sarvodaya leader had stayed at the Express guest houses on occasion.

Mrs Gandhi questioned the widespread notion that JP was the nation’s conscience keeper. Others, she pointed out tartly, were equally concerned about people’s welfare and the need to cleanse public life of weakness and corruption. The misunderstanding between the two leaders, far from clearing up, now increased, JP noting sadly that he was ‘only a private citizen, but I have my self-respect’.

Wherever he toured, JP received a rapturous response. Apart from the increase of corruption in public life, there was also much discontentment because of rising prices, thanks to two failed monsoons and a rise in international oil prices.

Buoyed by the public support for his crusade, JP called for a conference of all opposition parties to help channelize the enthusiasm of the people into a nationwide movement. The opposition parties were naturally delighted to have an icon like JP championing an anti-Indira Gandhi front.

On 1 November 1974 Mrs Gandhi and JP had a long meeting in Delhi. The PM offered a compromise formula. She was willing to dismiss the Bihar government provided JP ended his campaign and there were no further agitations for the dissolution of other state assemblies.

JP declined and the meeting ended in bitterness. JP handed over to Mrs Gandhi the letters written by her mother, Kamala Nehru, to his wife, Prabhavati. (Prabhavati had passed away in 1973.)

Kamala’s letters to Prabhavati, to whom she had become very close, revealed her innermost thoughts. She wrote of her deep sense of loneliness because of her husband’s frequent absences, and her feeling of isolation in her in-laws’ home. In her later letters she confessed—something she was hesitant even to tell her husband—that she was increasingly turning towards God and away from a temporal life. ‘I made a big mistake by spending 35 years of my life as a housewife. If I had searched for God during that period I would have found him,’ she confided.

Just a few days after the talks between JP and Mrs Gandhi broke down, he became the target of a policeman’s baton while on his way to address a meeting in Patna. Photographs of Jana Sangh leader Nanaji Deshmukh trying to fend off the blow to JP’s forehead, and of JP stumbling and falling during the lathi charge, were splashed in all the newspapers the next day.

The battle lines between the two sides were getting clearly drawn. In the opinion of Mrs Gandhi’s disillusioned joint secretary B.N. Tandon, ‘The PM’s own ego, pride and corruption did not have the ability to stand up to JP’s moral roar.’

As JP’s movement spread, Mrs Gandhi attacked it with increasing stridency. She accused the movement of encouraging violence and held it responsible for Lalit Narayan Mishra’s murder. Her government’s attitude was that force was the best way to stamp out the movement.

When JP was alighting from the train at Ludhiana, someone came from behind and tried to grab him, fracturing his neck bone. In Calcutta, a few armed Congressmen surrounded his car and attacked it with lathis.

In Patna, JP’s procession was fired at from a flat belonging to a Congress MLA. The Congress’s ally, the CPI, accused JP of being anti-national. JP responded, ‘It might sound vain, but the day JP becomes a traitor to the country there would be no patriot left.’

JP did have a few supporters in the Congress who were bold enough to openly display their affection for him. In November 1974, Chandra Shekhar, a Congressman and former socialist who refused to toe the party line, held a reception for JP in Delhi. Apparently around fifty Congress persons attended the dinner.

Chandra Shekhar was unperturbed by his party’s disapproval. He felt JP’s campaign should be viewed in the correct perspective. In his magazine, Young Indian, Chandra Shekhar wrote that since JP’s movement was not a fight for power it would be difficult to defeat him with the help of power.

After the Allahabad judgment, when the High Court declared Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractices, JP demanded Mrs Gandhi’s resignation pending her appeal to the Supreme Court. It was decided to launch a campaign throughout the country from 29 June to 5 July 1975 to urge her to honour the Allahabad judgment in spirit. Mrs Gandhi felt cornered.

On 25 June 1975 Morarji Desai, in an interview to Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, declared, ‘We intend to overthrow her, to force her to resign. This lady won’t survive this movement of ours.’

Defending her imposition of the Emergency to Pupul Jayakar, Mrs Gandhi claimed, ‘You do not know the gravity of what was happening. You do not know the plots against me. Jayaprakash and Morarjibhai have always hated me. They were determined to see that I was destroyed and the government functioning paralysed. How could I permit this?’ Mrs Gandhi’s eyes grew moist with unshed tears as she talked about her relationship with JP. ‘Jayaprakash’s wife Prabha was very close to my mother but with her death relationships have altered. Jayaprakash has always resented my being Prime Minister.’

…JP was arrested from the Gandhi Peace Foundation at around 3 a.m. on 26 June, and kept in custody in a guest house in Sohna, together with Morarji Desai, although the two were not allowed to meet each other. During his three days at the guest house, JP was examined by doctors who claimed he had a heart ailment. This was the first time JP learnt that he was suffering from such a disease. He was now moved to AIIMS, Delhi, the premier government hospital in the country, for further medical examination. After two days at AIIMS, he was flown to Chandigarh in an IAF plane and admitted to the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research at Chandigarh.

JP’s ordeal during the Emergency was painful, solitary and, indeed, heartbreaking. His health slowly deteriorated. He wrote in his diary on 21 July 1975, ‘My world lies in shambles all around me. I am afraid I shall not see it put together again in my lifetime.’ But he did not buckle, continuing to write frequently to Mrs Gandhi, refuting her canards against his struggle. She never deigned to write back. The most disturbing aspect of JP’s incarceration was the suspicion, which JP himself did not rule out, that some people might have deliberately tried to damage his kidneys.

During his 130 days of detention, JP remained in solitary confinement. ‘The reason why a month in prison appears like a year is my loneliness,’ he reflected in his diary. ‘The company of other detents might have helped. . . . Of course doctors, nurses and police officers used to see me but they would only enquire after my health. . . . There was no one with whom I could converse freely. As soon as any doctor or nurse enters the room a policeman follows.’ His guards, in fact, occupied several rooms on the entire floor.

JP compared the callous attitude of the Indira government to the British authorities when he was prisoner, during the Quit India movement. In 1942, when he had complained of solitary confinement the British had acceded to his request and allowed Ram Manohar Lohia, his colleague, to meet him for an hour daily.

There was a long corridor leading to the room where JP was kept as a detainee in Chandigarh. Armed sentries were posted on either side of the room. He was only permitted to take a walk outside after sunset. A writ was filed in the high court protesting the ill-effects of such treatment on a seventy-three-year-old man. He was finally transferred to the hospital rest house located in the campus…

…In October 1975, JP began to suffer from acute and continuous pain in his lower abdomen. All kinds of investigations were done, but nothing was found. The medicines given by the doctors brought temporary relief, but the pain recurred and JP continued to suffer from acute discomfort. His hands and legs were swollen. His under-eye area was so swollen that it hung over his face, giving him a deathly appearance.

JP’s brother Rajeshwar Prasad had met him in the first week of November and was alarmed by his physical deterioration.

Without his brother’s knowledge Prasad wrote a letter to Indira Gandhi: ‘I have very serious apprehensions that if his [JP’s] condition continues like this he might not survive for more than two months. This is causing us great anguish. I have not discussed my anxiety with JP nor mentioned that I would be writing to you, but I feel I must apprise you about his condition so that you can make your own assessment. Apart from the great personal tragedy that his loss would mean to our family, it is for you to decide whether it would be in the best interests of the government, if JP dies in jail.’

On 12 November 1975 JP was released on parole. Clearly Mrs Gandhi agreed with Prasad that his death in jail would not be in the best interests of the government. L.K. Advani noted in his diary, ‘Neither generosity nor humanitarian considerations had prompted his release. The motivation was sheer political self-interest. The parole announcement betrayed it very clearly.