How The UPA Government Got Away With Rs 1,200 Crore Pulses Import Scam

Seven years on since the CAG found fault with the UPA government’s decision to import pulses during 2006-11, nothing has been done to find out those responsible for the huge losses.

In December 2011, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) came out with a “Performance audit on sale and distribution of imported pulses”. It found that the then United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government’s decision to import pulses and distribute them was flawed, and it resulted in only favouring large private traders.

Soon after the CAG report was published, the media reported that the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) would probe the import of pulses during 2006-11 as a follow up to the CAG audit. Seven years on, nothing has been heard about this yet.

While scams concerning 2G and coal during the UPA hogged the limelight, the scam in import of pulses did not get the attention it deserved.

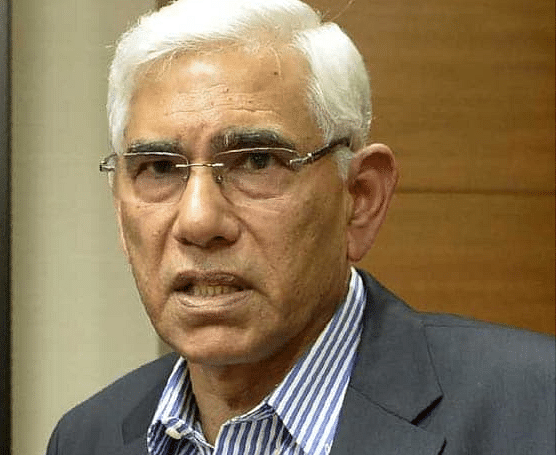

The then CAG Vinod Rai pegged the losses to the government due to the import irregularities at over Rs 1,200 crore. Interestingly, 75 per cent of the losses were incurred on importing yellow peas, promoted as an alternative to pigeon pea (tur).

The other interesting aspect was that within a few months of the pulses import starting in 2006, the CBI had looked into a complaint on irregularities in tenders floated by STC (State Trading Corporation) to import black matpe (urad).

The complaint against STC and its officials was that they did not follow the norms for floating the tender. The tender was kept open for a shorter period than normal and they did not go for a retender.

Be that as it may, what is this pulses import scam all about? In an effort to keep domestic prices of pulses on leash and to bridge the demand-supply gap, the UPA government came up with two schemes in 2006 and 2008 to import and distribute pulses in the country.

The first scheme, launched in May 2006, was to allow the National Agricultural Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) to import pulses on government account and reimburse losses if any. The reimbursement could be up to 15 per cent of the landed cost of the consignments. The scheme was extended until 2011.

The UPA government later nominated MMTC, PEC and STC — all government agencies and arms of the Commerce Ministry — as designated agencies to import pulses. Initially, NAFED was allowed to import 60,000 tonnes of black matpe (urad), mung bean (moong) and gram (chana) in 2006-07.

From 2007-08 to 2009-10, these agencies were allowed to import 1.5 million tonnes of pulses, while in 2010-11 they were asked to ship in 750,000 tonnes.

Up to 50 per cent of the quantity of pulses targeted for imports was to be yellow peas from 2007-08. All the four agencies were jointly asked to meet the import targets by the government.

Pulses imported by NAFED were to be distributed through Kendriya Bhandars, State Civil Supplies Corporations/Departments and other channels identified by the Food and Public Distribution Department at the Centre.

A committee of secretaries (CoS) decided that claims of the importing agencies for losses would be reimbursed by the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA), subject to the scrutiny of the audited accounts for the relevant period by the Cost Accounts Branch, Department of Expenditure, and Ministry of Finance.

A decision was also taken to rope in the Ministry of Commerce for coordination of import arrangements. In March 2011, the empowered group of ministers decided to discontinue the scheme as the government found that private traders were importing more than these agencies without any support.

The other scheme was introduced on 20 November 2008 with the UPA government deciding to import pulses for distribution among below poverty line (BPL) families through ration shops.

The National Cooperative Consumers Federation of India Limited (NCCF) was added to the list of nominated importing agencies.

Imports were to be made based on communication received from state governments on the requirement for each type of pulse. About 400,000 tonnes of pulses were to be imported with BPL families getting a subsidy of Rs 10/kg including administrative costs, margins and interest payable to importing agencies. A total outlay of Rs 400 crore was made for this pulses distribution scheme.

The agencies were given a deadline of 31 March 2009 to distribute the pulses to BPL families. The scheme got periodic extensions until 31 March 2012. A feature of this scheme was that the importing agencies were to be reimbursed the cost within 30 days.

The CAG audit looked at various aspects of the domestic pulses scenario, including imports by private trade that increased during 2009-2011. It found out that retail prices of pulses increased at a much faster rate than the corresponding wholesale prices during the period.

Though the designated agencies imported pulses on government account, retail prices kept on increasing during 2006-11. This pointed towards increasing control of the market by private traders that led to an overall increase in the prices of all major pulses during this period.

The audit found out that there was considerable shortfall in actual import and domestic disposal of pulses vis‐a‐vis the targeted quantities by the importing agencies. In 2009-10, the shortfall in imports was 76 per cent, while the shortfall in disposal of imported pulses was 50 per cent in 2008-09 — defeating the very objective of the scheme.

STC, in response to questions raised on shortfall by CAG, said that it had asked importers to minimise their losses and imports were lower primarily to cut losses. On the other hand, MMTC said imports were lower as global prices were higher.

The audit said that this was a contradiction in the implementation of the schemes where a target had been fixed for imports but the importing agencies were asked to cut losses.

The CAG audit also found undue delay extending upto 40 days, especially at the Kolkata port, in clearing the imported consignments and thus causing avoidable losses to the tune of Rs 42.71 crore.

The most important finding of the CAG audit was that NAFED contacted states for off-take of the imported pulses but it did not receive any positive response from them. On the other hand, PEC and STC did not contact any state for distribution of the imported pulses.

In view of this, NAFED disposed of the entire stock of imported pulses by floating open tenders as well as through the National Spot Exchange. Finally, all agencies sold the imported pulses in the open market through the tendering process.

This, the CAG audit observed, defeated the entire objective of importing pulses as no accountability was fixed for such a major lapse. The CAG audit reviewed the process of sale through tender process and found more glaring irregularities.

One, the tenders stipulated that minimum bid quantities ranging from 200 tonnes to 1,000 tonnes with payment of earnest money deposit (EMD) for the bids between 5 and 30 per cent.

The successful bidders were given time from 15 days to 90 days to lift the consignments and paying the balance amount.

When questioned about the high minimum bid quantities, the agencies justified them on the grounds that they were looking for only serious bidders. But these conditions resulted in just four private parties — LMJ Overseas, R Piyarelall Imports and Exports Pvt Ltd/RP Foods Pvt Ltd, Prime Impex and SRS Pvt Ltd — lifting 73 per cent of the quantity test-checked during the audit.

Ironically, all these companies, except LMJ overseas, were among the top 10 importers of pulses during the period. This, the CAG audit said, prevented the participation of smaller players and proper distribution of imported pulses. It said that the process pointed towards the cartelisation in purchases of imported pulses leading to lower sales realisation by the agencies.

The CAG concluded that consequently, delayed and opportunistic release of pulses by big private parties in retail markets could not be ruled out. The audit report observed that even after sales of imported pulses, there were inordinate delays in lifting of the stocks by the successful bidders.

As a result, imported pulses (the bulk of which constituted yellow peas) were not made available in the market promptly to keep prices on leash. The time taken to lift the stocks ranged from 35 days to 670 days, with the government failing to ensure timely lifting of the stocks.

STC and MMTC conceded that some bidders took a longer time to lift the stocks. The CAG audit said it led to shortage of pulses in the market and pointed to hoarding that led to rise in domestic market prices.

Scrutiny of the entire exercise showed that R Piyarelall and Prime Impex Limited had dual business relationships with STC, MMTC and PEC. First, as associates of STC, MMTC and PEC, R Piyarelall and Prime Impex Limited imported pulses through these agencies on private account.

STC, MMTC and PEC essentially lent their names to such transactions and funded the purchase through letter of credits, by charging ‘trading margins’ on these private firms. Import quantities, specifications, prices, delivery schedules were all decided by these associates.

Then, STC, MMTC and PEC carried out ‘high seas sales’ with these associates which led to the latter taking possession of the imported consignments.

As ‘buyers’ of pulses imported by STC, MMTC and PEC on government account, R Piyarelall and Prime Impex Limited bought large quantities of pulses from the public sector undertakings. This, obviously, meant these companies got subsidies for their own purchases as they were the importers as well as buyers.

The role of STC, MMTC and PEC vis‐a‐vis R Piyarelall and Prime Impex Limited, pointed towards conflict of interest. The CAG audit said the nominated government agencies like STC, MMTC and PEC facilitated import of pulses on private account to large private buyers, who had substantial control over the pulses market.

At the same time, they sold pulses (imported on government account) to these very buyers at a huge loss compared with the imported prices. Thus, agencies like STC, MMTC and PEC were unable to dispose of imported pulses on time as the prices offered by bidders were substantially lower than the import prices and prevailing wholesale prices.

As a result, all the nominated agencies had to sell the imported pulses consignments at substantial losses totalling Rs 1,201.32 crore. Reasons attributed for the losses were increases in global prices of pulses, depreciation of the Indian rupee, exchange rate fluctuations, lower sales realisation than the landed cost, sharp fall in crude oil, ocean freight charges and global meltdown.

The CAG audit found the 75 per cent of the losses were incurred in importing yellow peas. The audit pointed out that on 4 November 2008 the government decided not to go in for further import of yellow peas; yet at a Cabinet meeting in March 2009 it decided to import 750,000 tonnes of yellow peas and dung peas.

The Ministry of Commerce justified the continuous import of yellow peas, despite poor consumption, to the profits earned during 2007-08. However, prices of yellow peas crashed in the second half of 2008-09 leaving the nominated agencies holding the stocks imported at higher prices.

The audit said the government failed to reassess the country’s requirements and found imports of yellow peas, despite holding huge stocks, incomprehensible. The CAG regretted that no independent agency was asked to evaluate the efficacy of the decision to import pulses.

The scheme to import pulses and its implementation lacked clear directions on the government’s part. On the one hand, the nominated agencies, all government firms, were expected to import pulses on commercial principles and risks, while, on the other hand, they were led into a situation where there was no escape from importing even if the losses were beyond the stipulated 15 per cent of the landed cost of the pulses.

The CAG audit reported that the Ministries of Consumer Affairs and the Food and Public Distribution did not monitor the imports closely to ensure that they reached the intended beneficiaries.

Thus, both schemes were found to have not met their objectives with fingers being pointed at some private traders benefitting.

There are two issues at stake in this whole import episode. One, imports were planned to rein in prices and ease consumers’ concern. This never happened, as the CAG audit observed a rise in prices throughout the period.

Two, Indian farmers didn’t benefit from the higher price and the imports only filled up the pockets of a few private traders.

Nothing more than noises of a CBI investigation was heard on the issue after the CAG report. Someone gained unduly from the Rs 1,200 crore loss incurred by the government agencies but no effort has yet been made to get to the bottom of the issue.