PSU Bank Recap: Government Practices Need More Reforms Than Just The Banks

Reforms in public sector banking have more to do with how the government deals with banks than with what bankers have to do to lift themselves up by the bootstraps.

The announcement of a Rs 88,000 crore recapitalisation plan for public sector (PSU) banks is – from an immediate perspective – just what the doctor ordered. Without this life support, they are simply not in a position to lend fast enough to revive growth, burdened as they are with loads of non-performing assets (NPAs). At last count, PSU banks had over Rs 734,000 crore of bad loans on their books.

However, there is a difference between treating a patient’s short-term medical complaints and creating a long-term wellness programme that will make the need for regular medical attention unnecessary.

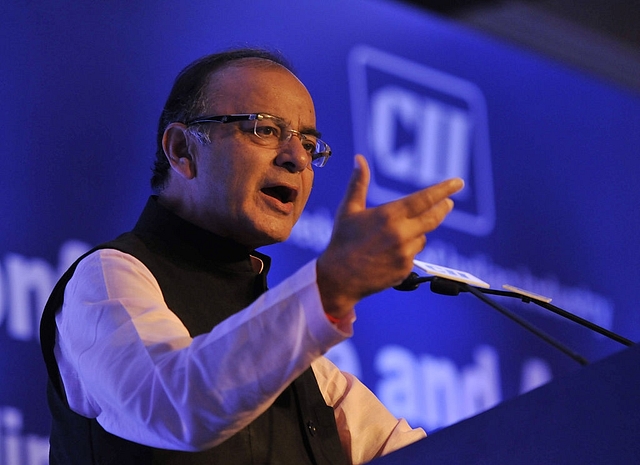

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, while announcing the package yesterday (24 January), said that an “institutional mechanism” was being set up to “ensure that what happened in the past is not repeated…”. But there is no way he can avoid a repeat after the next bout of irrational lending by public sector banks, even assuming the “reforms” are implemented in toto.

But the government should ask itself: is the problem with banks, or the institutional structures that restrict public sector bankers from giving their best?

Broadly speaking, the “reforms”, according to a Mint report, include the following: revamp of lending practices, better stressed asset management, digitisation and financial inclusion, easier financing of micro, small and medium enterprises, monetisation of non-core assets, differentiated banking strategies based on core strengths, ease of banking for customers, and better rewards for bank employee performance, among other things.

Before we take up many of these “reforms” for closer analysis, the very fact that almost all banks but one – Indian Bank – have got recap funds suggests that the worst performers will get the most money. This can hardly be a spur to better performance. Of the 20 banks that will get government money this year, 11 are currently under “prompt corrective action” by the Reserve Bank of India (a kind of short-term ICU ward for banks seriously in trouble), and they have got Rs 52,300 crore. The rest got Rs 35,800 crore. Three out of every five rupees is going to the prodigals.

The banks in the ICU include Bank of India, IDBI Bank, Uco Bank, United Bank, Central Bank, Allahabad Bank, Oriental Bank of Commerce, Corporation Bank, Indian Overseas Bank, Bank of Maharashtra and Dena Bank. IDBI Bank, which had gross NPAs of over 25 per cent as at the end of the September 2017 quarter, got Rs 10,610 crore. So, one of the worst performing banks got the biggest booty.

Now, let’s look at some of the reforms, which will involve banks signing on to improve these parameters in order to be eligible for the recapitalisation.

The first item on the agenda is revamp of lending practices to the corporate sector. While banks are anyway supposed to adhere to sectoral, group and company exposure limits, the reality is that most bad loans relate to lending to infrastructure and heavy industry projects, including power and steel. The problems in the power sector were sorted out – at least temporarily – by asking states to raise loans and write off the losses of their distribution companies, but the fundamental question is this: should banks at all be lending to infrastructure and capital-intensive projects with long gestation periods? When bank liabilities (deposits) are short-term, they should not be lending long-term beyond a certain limit that is backed by adequate capital. While this is the big issue that needs tackling, will this change even after the reforms are implemented when big ticket lending is almost always the result of government nudges and policies?

Then there is the question: why will banks reform their lending practices when they are almost in a direct reporting relationship to ministry bureaucrats and politicians? The reform that is needed is formal insulation of bank management from government, but this has not been addressed institutionally so far.

Second, there is stressed asset management. While this is obviously a no-brainer, given that gross bank NPAs (public plus private) are heading towards the Rs 10 lakh crore mark, one has to ask whether public sector bankers are in a position to make the right decisions on which assets to write off, which promoters and projects are worthy of a loan recast, and which assets should be sold at throwaway prices under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code. The last-named option is intended to force banks to find resolution for bad loans, but not all bad loans are worth putting into a garage sale.

Making these choices involves risk to the top management, since they can be accused of favouring one promoter or giving a long rope to another. If a bank chief executive officer has one or two years to retire, why would he risk having his decisions questioned after retirement by setting the Central Bureau of Investigation or the anti-corruption bureau after him? It is best to kick the can down the road and let his successor handle these choices. Unless the government insulates bankers from excess scrutiny by the vigilance commission and from harassment, where every bad loan is treated as evidence of corruption, you can’t get improved stressed assets management. Quite simply, the reform that is needed is legislative and procedural at the government level, and not necessarily at the level of banks. It is also worth giving top management a minimum tenure of five years, so that they have time to deliver.

Third, there is digitisation of banking and financial inclusion. Once again, reform needs policy backing. The main implication of digitisation is fewer branches, fewer employees and fewer ATMs, and a shift to non-physical modes of banking (wallets, mobile and internet banking, and other methods of e-payment). When confronted with a digital challenge, an HDFC Bank or a Yes Bank can easily cut down on employees by 11,000 or 2,500 without batting an eyelid, but can any public sector bank do so? Even a voluntary retirement scheme needs ministry sanctions, and may end up riling the unions. Moreover, a shift to digital banking means attracting higher skilled workers in areas like cyber security, product development and marketing, and fewer lower-skilled workers in other areas. What private bankers can choose to do easily (pay top dollar for top talent) is almost impossible in a union-dominated public sector banking space. Again, the areas that need action are in the government’s hands more than with bankers.

Fourth, there is the question of rewarding high-performance employees. In a seniority-driven public sector, and where pay differentials between officers and non-officers are small, it is tough to create reward structures that are meaningful, unless the latter category is eliminated in stages, and all employees are considered officers who can then earn differential pay based not on over-time, but measurable performance. This is not a problem individual public sector banks can handle, and needs to be sorted out at the policy level and with a total agreement with the unions on how this will work.

Fifth, the ease of financing for micro, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is obviously important, for the big companies anyway don’t need banks to raise money. The latter can use commercial paper, deposits and capital markets for funds. For most banks, small and medium enterprises hold the keys to lending margins, but most of India’s SMEs are in the “informal” sector, where a big chunk of their transactions are in cash, and not captured in the books.

Banks can lend only when they see cash flows captured in the books. Demonetisation and the goods and services tax are measures that will seek to formalise more enterprises, but this is a work-in-progress. And resistance to formalisation by those used to avoiding taxes and compliance with regulations means progress will be slow. Lending more to these sectors means that the government will have to work on two fronts: make compliance for the informal sector easier so that it joins the formal sector, and, two, stop mandating banks to lend by executive fiat. Again, while banks have to develop the necessary skills in identifying good credit prospects from millions of small companies, it is the government that has to ensure that they formalise themselves steadily, making it easier for banks to lend to them.

In one line, here’s the takeout: reforms in public sector banking have more to do with how the government deals with banks than with what bankers have to do to lift themselves up by the bootstraps.