The HDFC Bank Dilemma: How To Keep Its Iconic CEO And Its Best Top Managers

Companies cannot let go easily of established leaders, for they bring stability and experience; but they cannot allow them to block the supply chain of future leaders from seeking career growth.

Each company needs to find its own golden mean.

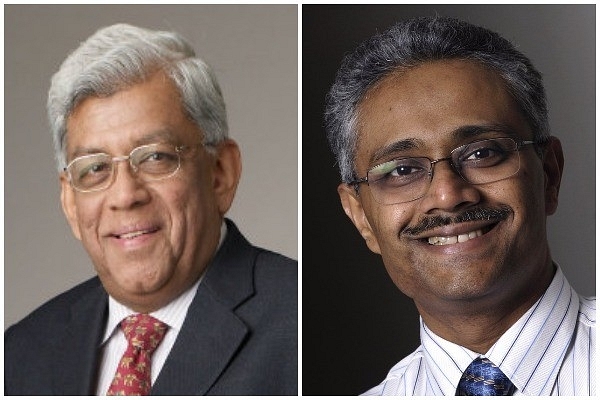

The sudden resignation of Paresh Sukthankar as deputy managing director of HDFC Bank and the earlier report that 25 per cent of shareholders were seeking the removal of Deepak Parekh from the board of HDFC are one of a piece: they bring into sharp focus the issue of how long iconic chief executive officers (CEOs) or founders should stay on at the helm and finding the right successors to them at the right time.

This is always going to be a dilemma: when should a larger-than-life founder/CEO leave (or withdraw from executive or operational roles), making way for an orderly succession? What is the loss to the company from the loss of experience and reassurance that iconic leaders bring when they are forced by age or other considerations to leave? Equally important, what is the loss to a company when its brightest managers find the C-suite blocked for decades when other career opportunities beckon?

This is an issue not just for successful institutions like HDFC and HDFC Bank, but all companies that have not passed cleanly into regular succession plans over time, where no CEO is considered indispensable.

In recent years, we have seen companies going through a rough patch when promoter-CEOs leave the scene prematurely (as in the case of Narayana Murthy at Infosys or Ratan Tata at Tata Sons), and we could see more concerns surface when promoters like Shiv Nadar at HCL Tech and Azim Premji at Wipro also walk off into the sunset.

The dilemma is this: great leaders bring great stability and reassurance to great companies, especially for investors; but great leaders also make it difficult for their successors to emerge seamlessly, as the second-in-line wait endlessly for their chance, and additionally face the prospect of being constantly compared to the icon in terms of their everyday performance.

In Sukthankar’s case, he was just 55, and widely expected to step into CEO Aditya Puri’s shoes when the latter turned 70 in October 2020. So, his exit is a big loss to the company. While one does not know the exact reasons for his exit, one can suspect that he might see better opportunities elsewhere, where he might land the top job two years before he probably could at HDFC Bank. In the process, he gets out of the shadow of an icon, a pressure that would have been unbearable at his old bank, where his every move would have been perennially compared to Puri’s record.

Many large investors seek the safety of the icon they know when the companies they were involved with flounder early during the tenures of their successors, often due to a change in business conditions or new challenges. This is one reason why Infosys investors loudly demanded the return of Narayana Murthy in 2014 after the CEO, S D Shibulal, was unable to reverse a structural slowdown in growth. Murthy quickly inducted a successor in Vishal Sikka, but found that his values were not that of the old Infosys he built. Sikka had to make way for a new CEO, this time inducted by a new chairman – the old reliable, and Murthy’s preferred successor at Infosys, Nandan Nilekani.

In the US, Procter & Gamble brought back CEO A G Lafley in 2013 when his successor failed to reverse a continued slide. Starbucks brought back its old CEO Howard Shultz eight years after he left the company in 2008, and it is only this year that Shultz said his final goodbye, probably because he wants to run for president in 2020. Apple brought back Steve Jobs when the company was going nowhere in the 1990s, some years after his board ousted him from his own company. Luckily, his cancer was known, and investors started looking towards Tim Cook even while Jobs was around.

There is no one answer to the problem of iconic founders/CEOs staying on too long or leaving too early. But broadly one has to find a golden mean where they move out of the operating roles at the right age, but remain as key steadying factors on the board either in a non-executive capacity as chairmen or emeritus, stepping in (but behind the scenes) only when the new incumbent needs help and stepping back when he doesn’t.

The short answer is this: companies cannot let go easily of established leaders, for they bring stability and experience; but they cannot allow them to block the supply chain of future leaders from seeking career growth. Each company needs to find its own golden mean.

In the case of Infosys and Tata Sons, both Murthy and Ratan Tata probably left too early, when their successors needed their backing and vigilant eye. It’s not about the age they left their executive roles; it’s about leaving when their successors were not ready or good enough to take their place.

This ought to be the guiding principle. You should stay as long as your successor isn’t ready. Once he or she is, you can walk into the sunset. In Deepak Parekh’s case, those seeking his ouster were certainly wrong, for the operating boss at HDFC is Keki Mistry, not Parekh. In HDFC Bank’s case, probably the lack of clarity on succession after Aditya Puri has been a problem. Time to rectify it. Sukthankar’s exit is a signal.