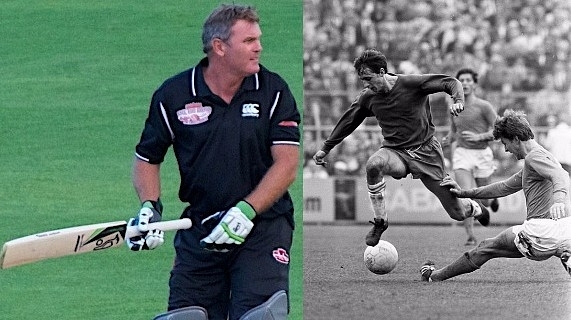

Crowe, Cruyff: The Game Changers

Dutch footballer Johan Cruyff and New Zealand cricketer Martin Crowe passed away in March. History will remember them as great players. They revolutionized sport with their vision and willpower.

Third of March had a sad reality to share. New Zealand’s former captain Martin Crowe lost his final battle with cancer.

On-field heroics of the former Dutch playmaker-skipper Johan Cruyff returned to our lives after the once-chain-smoking legend went away on 24 March 2016, also felled by cancer.

Crowe, while not being a Sunil Gavaskar or a Sachin Tendulkar, was an accomplished and stylish batsman, whose career was cut short because of susceptibility to injuries. As a footballer, Cruyff’s impact and influence exceed that of most in the modern-day game. Tutored by instinct, motivated by the twin forces of self-belief and confidence, he asserted his supremacy on the field during his playing days repeatedly.

In India, where cricket is sacrosanct for the majority of the population, Crowe, also because of his views as a commentator and columnist, will be spoken of very often. The heartening news is that awareness about international football is on the rise, with many more youngsters watching league titles than, say, one decade earlier. Hence, the emphasis on the iconic Cruyff, who taught innumerable lessons to his protégés and followers before he left us.

Cruyff as a player was a craftsman at work, whose near-impeccable control over the ball and understanding of what to do with it earned him numerous laurels. He masterminded the Cruyff turn, a dribbling manoeuvre in which he touched the ball with the instep of his crossing foot, pulled it back, made a 180-degree turn and sped past the hapless defender in an unexpected direction.

The Cruyff turn was famously seen in the Netherlands v/s Sweden tie in the 1974 World Cup when Cruyff fooled defender Ian Olsson and flew towards the goal. It was the first glimpse of an unforgettable moment, which revealed a new shade of a player par excellence. Four decades later, the Cruyff turn continues to be a vital dribbling technique.

Cruyff sharpened the craft of ‘Total Football’ in which fluidity of movement does away with the notion of playing in positions defined by the coaching manual. How to use space tactfully to dominate the opposition is the soul of ‘Total Football’. Fixed organizational structure becomes irrelevant, replaced by a keen observation of the goings-on on the field and the need for quicker responses to the need of the moment. Play anywhere, anytime, knowing why you are doing it: that, in brief, was the way Cruyff played his game.

Cruyff, who had honed the philosophy, masterminded the Netherlands’ journey to the finals. The Dutch had beaten Argentina (4-0), East Germany (2-0) and Brazil (2-0) on their way to the finals, while the Germans led by Franz Beckenbauer had to struggle in the initial stages.

Perhaps, that is why they had accumulated enough mental strength, which enabled them to counter Cruyff’s magic after he had been brought down in the German penalty area, resulting in a Dutch goal before the opposition had even touched the ball. The Germans recovered from the setback and beat the Dutch 2-1, but Cruyff may not have not been wrong when he remarked, “Maybe we were the real winners in 1974. The world remembers our team more.”

Like Cruyff but on a smaller scale in a game with limited reach, Martin Crowe impacted both as a batsman and a skipper, whose innovative approach while captaining his team in the 1992 World Cup will be remembered by every fan of the game.

His batting exploits receive more attention, and understandably so. Until today, he is a benchmark for evaluating the quality of batting that has emerged from New Zealand. A Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1985, Crowe was also named the Player of the Tournament at the 1992 World Cup co-hosted by New Zealand and Australia. As a batsman, he was in excellent form, but what made him stand apart from the other leaders was his captaincy.

He led a team like New Zealand, a squad that has traditionally suffered from its mysterious inability to capture the limelight as a unit for a long time. So what if the country has produced a legend like the all-rounder Richard Hadlee, a power killer such as Brendon McCullum, or the off spinner Daniel Vettori, among many others? New Zealand have not been the focus of international attention for a significant period, a reality that could have been redefined in the 1992 World Cup, which seemed to be theirs until something happened.

Crowe had guided his team to the semi-finals before being handicapped by an injury that debarred him from captaining in the entire match against Pakistan in the semi-finals, resulting in a shocking exit from the tournament. Inzamam-ul-Haq bludgeoned 60 from 37 balls, turned the game’s script on its head, and Pakistan sped past New Zealand as Crowe watched from a distance, his dream shattered.

Reflecting on his team’s loss in the semis, Crowe would say later: “With what unfolded, I made a massive mistake in not taking the field despite a hamstring injury, because I was trying to be fit for the final as opposed to getting the team through to the final.” How he managed to steer his team to an unlikely situation in which winning seemed to be a strong possibility is testimony to his greatness.

Crowe would have known—better than anyone else—that New Zealand needed some unusual strategies desperately. After all, his squad was hardly the best on paper. So, he played two cards, which none could have imagined he would.

Mark Greatbatch, who didn’t play the first two games, was introduced as an attacking opening batsman in the third outing. He was the ‘pinch-hitter,’ a yet-to-be-born concept in limited overs games, who had been advised to follow a one-line brief: Go after the bowling. Off-spinner Dipak Patel, an ordinary act at best, was asked to open the bowling.

When Greatbatch got an opportunity against South Africa, he went after their dreaded quicks, which included one Alan Donald. He scored 68 off 60 balls, and along with Rod Latham, he put on 103 in the first 15 overs. Against the West Indies, he hit 63 off 77 balls. Against India, he was even faster, scored 73 off 77 balls. Dipak Patel finished the tournament with eight wickets at an average of 30.62 at a miserly economy rate of 3.10.

The approach of Crowe in a limited overs tournament being played with coloured clothing and under floodlights would have far-reaching implications. Using an attacking opener to take the opposition apart – and that too, someone who had never played in any position except in the middle order earlier – would be a lesson for those seeking to capitalise on the fielding restrictions in the initial part of a limited overs match.

One may not be off the mark if one says that Sanath Jayasuriya, Adam Gilchrist and their likes happened ‘because’ Greatbatch under the stewardship of Crowe showed the way in 1992. Patel’s introduction during the initial stages inspired many captains to try to follow the same formula. Of course, they didn’t have a consistently comparable economy rate in the big arena, but then those who followed Greatbatch had learnt to prioritise runs instead of putting a hefty price on their wicket: and their team in trouble.

Far away from the world of cricket, Cruyff’s coaching skills and philosophy as a manager has resulted in a legacy, whose footprint wouldn’t fade: if the world doesn’t stop playing football. When he took over as the manager of Barcelona in 1988, the squad had won only one league title in 14 years. But, the quote-a-minute man said, “I know the club, and I don’t want history to repeat itself. If we want things to change, we must change history.”

The team that Cruyff built had international stars like Brazil’s Romario, Denmark’s Michael Laudrup, and Spain’s Pep Guardiola, Andoni Zubizarreta and José Mari Bakero. Having gathered such a promising line-up of players, Cruyff guided his Dream Team to a series of conquests, including UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup in 1989 and four consecutive La Liga titles between 1991 and 1994.

Cruyff insisted on possession football, which continues to be the trademark of Barcelona. He believed in the fundamental concept that when a team dominates the ball, it moves well, which creates more chances of scoring. The opposition has to deal with the pressure, which works to the advantage of the person who has the ball and, therefore, is in a far better position to evaluate the options and use the best one available to him. As he said, “There is only one ball, so you need to have it.” He taught his students, the answer to that important question. How?

Studded with exciting players and fortunate to have him as the coach, Barcelona enjoyed as many as 11 trophy wins when Cruyff was there to help the players with his strategizing – and motivate them with a mindset, which refused to take a loss lying low. He ended up being the most successful manager of Barca ever until Guardiola, whom he had taught, broke his seemingly strong record a couple of decades later.

The Spanish national team, which won the 2010 FIFA World Cup, was influenced by Cruyff’s tactics. So were the Germans, who went on to win the tournament in 2014. Arsenal’s manager Arsene Wenger has been influenced by Cruyff’s coaching methods; and so have others like the iconic Dutch defender Frank Rijkaard, who coached the national side later, former Danish player and manager Laudrup, who played for Barca when Cruyff was the coach, and numerous players, including Lionel Messi, Andreas Iniesta and Xavi.

In fact, Graham Hunter may not have been far off the mark when he wrote, “There shouldn’t be any real argument about it. Johan Cruyff is, pound for pound, the most important man in the history of football.” Romario said after his death, “I had the privilege to have you as a coach when I played at Barcelona. He was, without doubt, the best trainer that I had, your teachings will live on forever in my life.”

Crowe and Cruyff must not be compared. They were two innovators, who acted as influencers in two different forms of sport. What they are assured of is life after death.