Verses Which Produce Magic When Re-Read

भवित्री रम्भोरु त्रिदश-वदन-ग्लानिरधुना

स ते रामः स्थाता न युधि पुरतो लक्ष्मण-सखः ।

इयं यास्यत्युच्चैः विपदम् अधुना वानरचमूः

लघिष्ठेदं षष्ठाक्षर-पर-विलोपात् पठ पुनः ||

“Beautiful, the gods will lose face today.

You will see your Rama fall in battle

And that monkey army will go to ruin.”

“Loser! Remove the seventh syllable and repeat.”

And so, Sīta snaps at Rāvaṇa who’s tooting his horn. Let’s follow her instruction and remove the seventh syllable and see what happens—

भवित्री रम्भोरु (त्रि)दश-वदन-ग्लानिरधुना

Beautiful, the ten-faced-one will lose face today.

स ते रामः स्थाता न युधि (पु)रतो लक्ष्मण-सखः ।

You will see your Rama engaging in battle

इयं यास्यत्युच्चैः (वि)पदम् अधुना वानरचमूः

And the monkey army will advance a step.

How delightfully clever! Rāvaṇa’s boast has been turned on its head! This verse is found in the Hanuman-nāṭaka, which retells the Rāmayaṇa by cleverly quilting together verses from a diverse range of works, spanning several centuries. There is also a pretty story involving Kalidāsa and (who else?) Rājā Bhoja, in which the author is revealed to be none other than Hanumān. Hanuman or not, we must agree that the author must have been clever indeed to come up with this verse!

We now fast forward a thousand years and come to the prosperous kingdom of Mahīśūra (Mysore), which is flourishing under the rule of the benevolent Wodeyars, who were patrons of the arts (and often artists themselves). Among the āsthāna-kavis (court poets) of Krishna Raja Wodeyar IV, is Rāma Śāstrī who takes upon himself an extraordinary task— he wants to write an entire kāvya themed on Sīta turning the tables on Rāvaṇa’s boasts! The result of the next thirty years of work is the sītā-rāvaṇa-samvāda-jharī (Sīta and Rāvaṇa’s Conversation Cascade), on which rests today’s spotlight. The naive reader will run through the work noticing nothing special; but to those who know that there’s more than meets the eye, out pops the magic, leaving them wonderstruck at the gems hidden in the work. Here’s a first sample—

स्मृत्वा मां हृदि जायतेऽति-विनयः क्रव्यादमात्रेऽपि ते

भर्ता भूमि-सुते! सदानृत-गुणः तेऽतोपि सौख्यं कुतः? |

जाते मय्यसु-नायके तव सुखं स्यादेव किं दूयसे ?

किं रे! जल्पसि दुर्वचः खलमते! भूयोऽपि नेदं वद ||

“Your husband’s virtues are all deceit, Sīta.

How can you be happy with him?

But me— every Rākṣasa treats me with deference.

Now, if I were to be your husband

your happiness is guaranteed. Why do you wilt?”

“What’s this blabber, scoundrel? Don’t utter it again.”

Nothing odd right? Fluid versification, neat word order, simple words— it is everything a decent verse aspires to be. But I’ve already told you there’s a gem hiding there. So where is it? I’ll tell you. The last bit “bhūyopi nedam vada” “Don’t utter it again”, can also be read as “Read it with da in na’s place” by splitting “nedam” as “ne dam”. Now let’s replace all the na s with da s—

स्मृत्वा मां हृदि जायतेऽति-विदयः क्रव्यादमात्रेऽपि ते

भर्ता भूमि-सुते! सदादृत-गुणः तेऽतोपि सौख्यं कुतः? |

जाते मय्यसु-दायके तव सुखं स्यादेव किं दूयसे ?

“Your husband is firm in his virtues, Sita, could you be happier?

Even the Rākṣasas don’t look upon me kindly.

Once I’m dead, your happiness is guaranteed, why do you wilt?”

What a twist! Ravana’s boast has been turned turtle in one stroke!

Here is another verse; this time you need to delete a letter to effect the transformation (cyutākṣarī)—

परिक्षीणालस्यः समरभुवि रक्षःकुलपतिः

सलज्जः स्वस्तुत्याम् अमलहितमार्गैकपथिकः |

प्रणम्यस्त्रीलभ्यः सुमुखि विलसत्कीर्तिरिति च

श्रुतो नाहं? किं रेऽधम! मुहुरलं त्वां श्रुतवती ||

“I’m the King of Rākṣasas, dynamic in battle

modest about myself, traveller on a noble path,

Women flock to me and my fame is acclaimed

You know all this, don’t you, pretty one?”

“You’ve started again, you wretch? Enough. I’ve already heard you.”

When Sīta says “alam” “enough”, she secretly means “a-lam” “without letter la”. So deleting all the लs gives—

परिक्षीणास्यः समरभुवि रक्षःकुपतिः

सज्जः स्वस्तुत्याम् अमहितमार्गैकपथिकः |

प्रणम्यस्त्रीभ्यः सुमुखि विसत्कीर्तिरिति च

श्रुतो नाहं? किं रेऽधम! मुहुरलं त्वां श्रुतवती ||

I’m the wretched king of Rākṣasas

I lose face in battle

I’m always ready for self-praise

I bow to women

And am shrouded in ignominy.

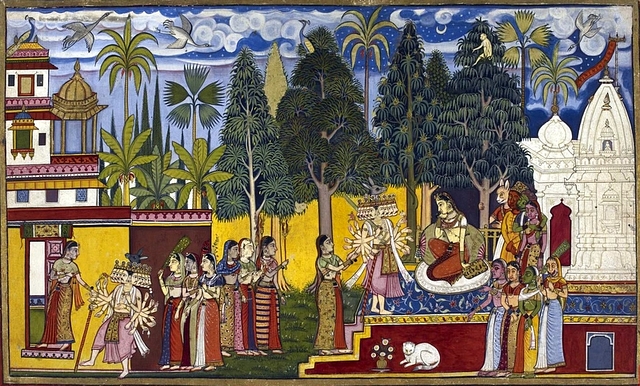

This kind of poetry, citrakāvya, is a kind of prestidigitation which derives its charm from the astonishment of the reader. The poet must give the verse a semblance of normality— as if there’s nothing strange going on at all. And then the bombshell is dropped, leading the reader wide eyed with surprise. Rāma Śāstrī shows consummate skill in this art. The concealment is done in various ways— by changing one letter, by changing two letters, by dropping a letter, by replacing a letter etc. There are even some verses written without concealment in honor of this inspiration, the hanumannāṭaka. Infact, Hanumān appears in this work too; he is surreptitiously perched on top of the Rosewood tree under which Sīta and Rāvana are having their exchange. He is delighted by Sīta’s defiance and soon heads back and reels out the whole conversation verbaṭim to Rāma.

It is in Hanumān’s voice that the entire work is written. Before ending the work, Rāma Ṣāstri express regret for not being able to write a full hundred verses, and says that he will offer a thousand salutations (sahasraṁ namaḥ) to anyone who can bring completion to the work. About fifty years later, Bacchu Subbarāyagupta accepted the challenge and wrote another fifty verses in the same vein— the abhinavā sītā-rāvana-samvāda-jharī. I quote one sample verse from the work—

क्षोणीनन्दिनि! राघवं कलयसे किं शत्रुभीतं सदा

चरित्राणि तव प्रियस्य नियतं भङ्गापवित्राणि हि |

मां मन्यस्व शुभावृतं पुरि जना जानन्ति यं सर्वदा

रे ! भङ्गावृतमेव ते तु वचनं जानामि चित्ते सदा ||

“Beautiful, why contemplate on the cowardly Rāma?

His conduct is disgraceful and inauspicious.

Know me, like the town folk do, as a virtuous man.”

“I know that your words are only out to insult”

The reversal of meaning is achieved by cleverly splitting the words as “re abhaṁ gāvṛtaṁ te tu vacanam” “Remove bha and put ga”. I’ll leave the flipped meaning for you to decipher.

The Rāmāyaṇa is atleast 2500 years old. The hanumannāṭaka came more than 1500 years after it. And more than a millennium later came Rāma Śāstrī. And half a century later came Bacchu Subbarāyagupta. This literary chain may not seem unusual at first glance, yet it is an extraordinary thing to happen in a language. Languages come with lifetimes of less than a millennium. Old English is as intelligible to me as Hebrew. Reading Geoffrey Chaucer is like wading through quicksand. Time will ensure libraries move Shakespeare from the literature section to history section. But frozen in time by the spell of Pāṇini, only Classical Sanskrit will remain untouched. A few hundred years from now, a young boy (or girl), having taught himself Sanskrit, may decide to write a work to top Rāma Śāstrī. The poet to top Kālidasa may well be born a thousand years from now. My own descendants may spend a sunday afternoon, sipping soylent, and laughing at their ancestor’s metrical misadventures. How absurd it is to label such a language dead! Immortal is more like it. I leave you with Kalhaṇa’s wonderful observation in Rājatarangiṇī—

वन्द्यः कोपि सुधास्यन्दास्कन्दी स सुकवेर्गुणः ।

येनायाति यशःकायः स्थैर्यं स्वस्य परस्य च ॥

Homage to good poetry.

Indeed, it beats even ambrosia.

For it renders immortal,

Not just the poet

But also his subject.