Indian kāma same as Western sexuality?

The Indian liberal dispensation presents a contrived and wrong equivalence between Western sexuality and Indian kāma

Shashi Tharoor’s article ‘PDA is in Our Culture. Hindutva Brigade, Take That’ represents a typical liberal response to the Hindutva protest against Valentine’s Day (VD) in particular and public display of affection (PDA) in general. While eschewing the threat and violence associated with Hindutva rhetoric and without wholly subscribing to their fantastical narratives of the Indian past, it is necessary to find some sensible common ground between the extreme positions on both sides of the debate. Since the extremism of the Hindutva point of view is well-known and enjoys a marginal position in mainstream media, it is the liberal argument that is in need of a forensic analysis, especially since it projects itself as pluralistic, tolerant, moderate and so on.

The first thing to note about the liberal argument is that over the past century it has undergone a radical change with regards to Hindu culture. In the heydays of Nehruvian secularism, when the Indian liberals were beholden to the techonological and humanistic progress in the West, there was hardly any discrimination between Hindu culture and Hindutva, and both were seen as equally retrogressive and marked as obsolete. But with the advent of post-modernity and cultural relativism, de-Westernization and valorization of the native culture became a mantra in the West itself and its ardent followers had no choice but to alter course. Today, Western scholars of Hinduism as well as Indian liberals both project themselves as the true champions of Hindu culture and the Hindutva brigade as its enemy. It is not just a coincidence that Tharoor refers in his essay to ‘the notorious “pulping” of Wendy Doniger’s erudite studies of Hinduism.’ Her by-line ‘the Hindutva-vadis are the ones who are attacking Hinduism; I am defending it against them’ is now the mūla-mantra of Indian liberalism, strongly evident in Tharoor’s essay.

It is not necessary to disagree with Tharoor’s echo of that sentiment when he says that the Hindutva forces have no ‘real idea of Hindu tradition,’ that ‘their idea of Indian values is not just primitive and narrow-minded, it is also profoundly anti-historical,’ and that they act ‘in the name of a notion of Indian culture whose assertion is based on a denial of our real past.’ Rather the question is how do we know that the liberal construction of the ‘real’ Hindu past is not just as imaginary as the alleged Hindutva delusion? After all the evidence provided by the liberal is hardly persuasive.

What the Indian liberal offers as argument are merely exhibits of some books on sex and expressions of erotic art in sculpture and poetry but what we do not know is their Wirkungsgeschichte (reception history) i.e. how were these texts and images received by audiences down the centuries, what role did they play in their lives and how did they collaborate with the other dimensions of their life?

Today ancient Hindu erotica means nothing more than an indigeneous argument for sexual freedom – to be invoked as an excuse for engaging in lewdness whether in art or in reality. Once you declare yeh kamasutra ka desh hai ‘this is the land of the Kāmasūtra’ then you have pretty much insured yourself against accusations of violating bhāratīya saṃskṛti. Yet the Kāmasūtra in its very first chapter locates itself within the trivarga (triad) of dharma, artha and kāma, enjoining its readers to practice all three at the appropriate stages of their life with brahmacaryam eva tv āvidyāgrahaṇāt i.e. celibacy until education is completed. And of the trivarga, the Kāmasūtra declares that dharma is superior to artha and artha is superior to kāma. I would like to see one advocate of the Kāmasūtra uphold these principles.

Likewise, when we come across sexual references in Sanskrit literature we need not hastily read them as indicators of a permissive culture. So, for example, even if Duṣyanta and Śakuntalā may have married the gandharva way, the kṣatriya hero initially hopes for her to be a daughter born of a kṣatriya wife, then consoles himself that she must be eligible somehow to wed a kṣatriya since his ārya mind had desired her, and finally inquires with her friends not only about her birth but even whether, as a girl brought up in a hermitage, she was eligible for marriage. Thus, even if it had been love at first sight, it was not blind and it is only after having confirmed that he was not violating any social norms in wooing Śakuntalā that Kālidāsa makes his Duṣyanta proceed with the affair. There is no Romeo and Juliet in Sanskrit literature.

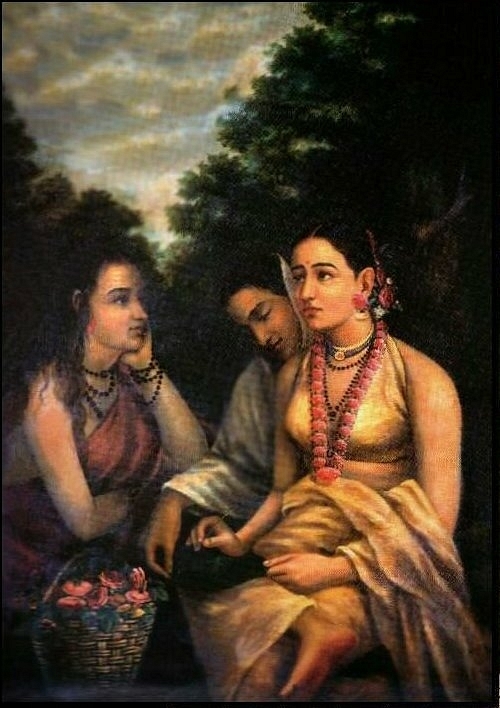

In fact, albeit explicit, kāma hardly occurs in isolation but always in harmony and balance with other aspects of human life. Thus, Bhartṛhari wrote the śṛṅgāraśataka (hundred erotic verses) along with the hundred verses on nīti (polity) and vairāgya (renunciation). In the same way, Jagannath Pandit’s Bhāminivilāsa gives space to karuṇa (compassion) and śānta (peace) rasas along with śṛṅgāra. In fact, most of the composers of amorous works were brāhmaṇas affliated with Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava or Vedānta sampradāyas, unlike today where erotic art is no longer produced by practitioners of dharma or as a limb of an overarching dharmic configuration but mainly by the opponents of dharma, as a political weapon to challenge it.

This is the critical issue of our times and we have hardly addressed it. Tharoor himself refers in his article to the anthology written by the 11th century Buddhist monk Vidyākāra which supposedly includes several highly erotic verses but he does not pose the obvious question which has long baffled modern scholars of that work: why was a Buddhist monk writing erotic poetry? How did it fit within his overall idea of Buddhist dharma? Unless we can answer these questions, we cannot infer, merely from the fact that he wrote erotic poetry, that he would have also approved of other sexual practices such as VD or PDA.

Likewise, Tharoor’s argument that “as late as the 11th century, Hindu sexual freedoms were commented upon by shocked travellers from the Muslim world” is also not satisfactory. Not only the Muslims, but as S. N. Balagangadhara notes in The Heathen In His Blindness, as late as the 16th century, European travellers to India were describing no less lascivious accounts of the super-casual sexual practices of the Hindus. Only, Balagangadhara further explains that in the eyes of the Christians, descriptions of Hindu “immorality” were inseparable from their “devil-worship” and “idolatry.” Sexual licentiousness was regarded as the best indicator of an immoral culture and Christian and Muslim travellers to India already knew that the Hindus had to be an immoral people because they were lacking in the true religion. This was the lens through which they saw and wrote about the Hindus but such accounts only inform us about the prejudices of the travellers themselves and nothing about the prevalent cultural practices of the Hindus.

Tharoor maintains a false sense of dichotomy when he suggests that “the central battle in contemporary Indian civilization” is between essentializing a supposedly true Indianness and respecting our cultural manifoldness. He makes a virtue of a necessity when he suggests that “India’s culture has always been a capacious one, expanding to include new and varied influences, from the Greek invasions to the British.” The problem with this view is that we are not able to distinguish this kind of malleability from the conduct of a spineless people who, like soft and tender grasses, will bend every which way even in the face of a mild wind because they have not the first clue about who they are and what they stand for. The Pañcatantra refers to this archetype as laghu-prakṛti (weak-natured) and describes them in this way:

laghor vikāras tanunāpi hetuna

calanti darbhāḥ śithile’pi mārute.

The meanest, pettiest causes

make shallow minds change and veer;

the pliant grass is set a-trembling

by lightest, gentlest breezes. (trans. Chandra Rajan)

What Tharoor regards as Indian “capaciousness” is a valorization of our failure to develop a criteria of independent judgement of what is right or wrong for us and merely to keep shaping ourselves in accordance with the latest intellectual fashion in the West. Thus, in the 19th century, instead of mounting a critique of monotheism, Hindu thinkers imagined their dharma in the image of Protestant Christianity, as a monotheistic religion gone awry. And at that time too, the protests by traditional Hindus of the denigration of their customs was pooh-poohed by the avant-garde camp as the defense of a false idea of culture. We are in the same mess today in which our liberal thinkers believe that in endorsing the sexual freedoms upheld in the West they are resurrecting an ancient Indian practice while those objecting to it in the name of tradition are ignorant of the very tradition they are defending. Ironically, it is the liberal scholarly establishment itself which traces the roots of Hindutva to the colonial construction of a Vedanta-based unified Hindu religion – or should it now be read as an instance of Indian “capaciousness”?

Tharoor’s notion of a “tolerance for difference” as the character of modern Hinduism is equally problematic as it is based entirely on the relationship between religion and sexuality as determined by Christianity. The premise is that sexuality has no place in religion and the only difference between Christianity and Hinduism is that the former suppressed it while the latter tolerated it. And so, the argument goes, if the Hindus are suppressing it now, they are emulating a medieval form of Christianity. But this argument is fallacious because kāma was never an extraneous graft ‘tolerated’ by Hindus, it was always an integral part of the Hindu religious discourse as a member of the trivarga consisting of dharma, artha and kāma.

By mindlessly equating Indian kāma with Western sexuality the rational Hindu is cornered into either accepting or rejecting both. Thus, Tharoor gives examples ad nauseum of kāma representations in Hindu tradition, asking rhetorically whether there is any place for them in bhāratīya saṃskṛti. But the point itself is basically invalid for on what grounds is it declared that Hindu kāma and Western sexuality are equivalent? This issue is not even addressed, let alone explained, but simply presumed to be true, just as 19th century Hindus believed that Indian dharma and Western religion belonged to the same category, and therein lies the proton pseudos, the root fallacy, of the whole argument.

It is not only the discourse on kāma that has become moribund in contemporary India, the whole triadic configuration in which kāma co-existed in balance and harmony with dharma and artha, has come undone. And the importation of Western sexual mores, far from resurrecting it, will only distort it further. Furthermore, it is obvious that Hindu erotic art has no place in contemporary Indian culture because, when it comes to professing their love to the world or romancing in public, our impassioned lovers never draw inspiration from it and make the initial move but merely copy the sexual behaviors observed in the West – and then invoke Hindu erotic art only as an afterthought to justify the indigeneous basis of their actions.

Neither Indian kāma nor Western sexuality persist in a vaccuum but always in relation with other facets of the culture. Repressed for centuries as a matter of shame and guilt, when sexuality finally expressed itself openly in the West it did so as a political statement, as the individual rebelling against religion, society and family. Even today, PDA, especially shown by inter-racial or same-sex couples, can be viewed as corollaries of the heterosexual acts of defiance a few generations ago. And when they are imported into India, they play the same role of pointing the proverbial finger at a society abiding by dharma.

Contrast this with Indian kāma which is intricately linked with spirituality and becomes the metaphor through which the human relation with God is both expressed and experienced. Can we even begin to imagine the sexual behaviors imported from the West as fulfilling a similar role? It does not matter if the Hindutvavadis do not get this but those who are drawing equivalence between Hindu and Western sexual behaviors should at least know better. It has taken us about two centuries to fully realize that there is a disjunction between Western religion and Indian dharma. How long is it going to take us to realize that there is a disjunction between Western sexuality and Indian kāma as well?