The other battle for Odisha

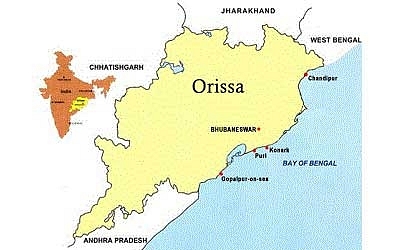

In the past one week, Odisha has been mentioned much more than it ever had been, in the entire of 2013. News channels spoke of ‘Jagatpuri’ and ‘Khudra’ districts being ravaged by the cyclone. Ofcourse it is another thing that no Odia might have heard these names in their lifetimes. People in the social media expressed solidarity with their Odia brethren on Day 1, praised the government and the administration on Day 2 and called Phailin an epic failure on Day 3. The chatterati, the intelligentsia and the common man knew about Odisha, talked about the fate of its people for one whole week. And, we can thank Phailin for that.

Now that the winds have subsided and only 23 people have lost their lives, it no longer makes any sense to talk about 3 lakh hectares of bumper crops destroyed. It also is not quite important to focus on 2 lakh people losing all their capital, their houses, their poultry, their boats, their nets in 6 hours. Failed crops, broken houses, interrupted power supply and washed away roads can wait. It is also not critical to talk about the herculean task in the hands of the government to go about bringing normalcy back to these ravaged districts. For, the rest of the country, the worst is over, the battle is won and Odisha will be talked about another day. During another cyclone or a flood, maybe.

But, for people living in Odisha and for the government ruling it for 13 years, coming out of the devastation left behind by Phailin is not the only battle at hand. It is not just a battle to bring the state back to normalcy, to allocate funds, to provide relief and rehabilitation. There is also the larger battle to make the Centre take a look at the state, its historical marginalization and ponder about the existence of the 4 crore Odias. The first demand to grant Odisha, special category status, entitling it to special assistance from the Centre came forward in the year 1979 through a legislation passed in the state assembly.

It has been 34 years since then and the demand keeps falling on deaf ears in the Centre. Successive governments at the Centre have come and gone but the marginalization of Odisha continues. There have been many unanimous resolutions passed in the state assembly to get special category status for Odisha, the latest one being on April 2013. Post the resolution, MPs from the BJD have repeatedly staged dharnas in the parliament premises, organized a ‘Swabhimaan Samabesh’ rally in Delhi and even the otherwise soft spoken Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik has attacked the Centre for its apathy towards the state.

The government has repeatedly pointed out the problems of a state which suffers from poor health, education and income indices, has a sizeable portion of tribal communities and faces the brunt of a natural calamity atleast once every year. Tribal communities comprise 22.8% of Odisha’s population and Scheduled Castes constitute 17.1% of the population. These figures are much higher than states like Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh who enjoy special category status. Even in terms of connectivity and infrastructural growth, Odisha lags behind in the average highway length and percentage share of railways. A dismal manufacturing sector, low royalty on minerals and a geographical terrain stalling infrastructural growth have festered this backwardness since decades. On one hand it is difficult for a state housing millions of poor and marginalized to generate revenue and on the other hand, it has to share upto 35% of the expenses in critical schemes.

This has created a cycle of impoverishment in the state which needs urgent central assistance. In such situations, a special category status for Odisha would mean that funds are allocated to the state on a 90-10 basis and taxes will be exempted for new investments. But, 34 years and the battle for getting Odisha its due continues.

While some call the long sustained demand as going to the Centre with a begging bowl, peddling one’s victimhood, others just choose to keep quiet and let the politics chart its own course. Sadly, no one cares to look at the reasons as to why Odisha demands a special category status and what it would mean for the people living in some of the most backward districts in the country.

So while the entire nation has taken out some time for Odisha, it is important that we take this time to talk about where the demand for special category status emanates from. Demanding Federal economic inclusion is not the result of institutional failure of the state amounting to false victimhood but a legitimate right to correct structural inequalities.

While every state needs to work on generating revenue and create a sustainable growth environment, it does not in any way negate the rightful claim of Odisha over funds which are earmarked for backward states. It is certainly not with pride that the demand has been voiced out. Nobody wants to revel in impoverishment or wear a badge of their underdevelopment. But, getting stuck in the value judgments about being backward will in no way help espouse the cause of the people living in abject poverty in the state.

The Backward Area Grants Fund (BRGF) was supposed to be a mechanism which will help create and sustain balanced regional growth and promote social inclusion. Why is it, that when Rs. 8750 crores was sanctioned by the central government for backward districts in West Bengal in 2011 while a meager Rs. 1700 crores was sanctioned for 19 backward districts in Odisha?

Again in the 12th 5 year plan period, Odisha was sanctioned a meager Rs. 1250 crore as opposed to Bihar which was sanctioned Rs. 12,000 crores for the plan period under BRGF. There are some states which have a higher per capita income than Odisha but are still enjoying the Special Category status. The ‘mixed results in infrastructure’ argument used by Montek Ahluwalia to justify the exclusion of Odisha from being granted special status, does not stand scrutiny when one takes a cursory look at the Human Development report 2013. The road length per million of population in Odisha is less than that of special category states like Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura and even Uttarakhand. Only 52.1% of households have access to electricity for domestic use which is less than the figures of all special category states. And this is after the spread of electricity to households has increased by 15% between 2002 and 2009.

The issue is not with granting the special status to other states. Nor is it about putting the burden of Odisha’s future on the Centre. The question is what is leading to the automatic exclusion of Odisha from being granted this status inspite of fulfilling all conditions (except that of sharing an international border). Can this tangible discrimination then be considered to be politically motivated?

Demographic diversity, natural calamities and a historical burden of impoverishment is continuously acting as a barrier to the development of Odisha. The fiscal structure of the state is getting stronger with the government working hard to create an investor friendly environment. But, that has not yet transformed the poor economic base of the state which still makes revenue mobilization difficult. But not all of the failed efforts at revenue generation can be blamed on the state government. Inspite of repeated demands to increase the state’s share in royalty for minerals mined in Odisha, there has been no change in the stand from the Centre. Therefore, inspite of being well endowed with mineral wealth, the state can hardly generate any revenue from it nor can it give the displaced population the desired rehabilitation and benefits of investment.

Even though the government has been able to bring down the infant mortality rate down from 95 in the year 2000 to 65 in the year 2009, it stands much more than the national average of 50. Maternal mortality rate has also gone down from 358 in the year 2001 to 258 in the year 2009 but is again above the national average of 212. Inspite of these staggering odds, the government has been able to gradually increase the value of health, education and income indices over the years taking the human development index in 2007-08 to 0.362 from 0.275 in the year 2000.

The most significant increase though has been in the literacy rate of the state. The rural literacy rate has increased from 54% in the year 2000 to 65.6% in 2008 and the urban literacy rate has increased from 76% in 2000 to 85.6% in 2008, which is higher than the national average of 84.3%. Tribal literacy rates though still continue to be dismal with 2007-08 showing literacy rates of just 46.8% which is much less than the other tribal dominated states of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. Though the gross enrollment ratio for primary and upper primary schools is higher than the national average, the same figures for schedule tribes tell a different story.

The Naveen Patnaik led BJD government has been one of the first parties to stand against the ordinance on Convicted Netas and has been a lone fighter against the amendment to keep political parties out of the ambit of the RTI. The media did not have much to say about both these issues until the former issue was hijacked by a crown prince and the latter was espoused by more parties like the TMC and the CPI. Now that the proactive measures by the states political and administrative establishment has delivered and have managed to contain the devastating effects of Phailin, the nation is looking towards the East and making this small coastal state stand out as an example.

There have been successive attempts at cleaning the political system in Odisha by weeding out corrupt elements from the party and the ministry since 2001. The fiscal structure of the state is improving. There have been relative advancements in health and education indices. The last 13 years have been a change from the corrupt regime of the Congress. But, the way ahead for Odisha is long and arduous. And it needs the help of the Centre. Not as charity, but as a right. A politically neutral BJD which has kept equal distance from the Congress and the BJP in the past 5 years is a voice which the Centre chooses to ignore. Probably the alluring idea of political dividends does not apply here and the conscientious voice of the Congress prefers to stay silent when it comes to Odisha.

But, if it takes a cyclone to make people sit up and take notice of Odisha, then this is the time to appeal again to reason and integrity. People in Odisha need much more than sympathy and prayers and the state government needs much more than selective adulation. Together, they need a chance to chart their destiny and for that they need the assistance that they rightfully deserve. Listen to Naveen Patnaik. He will tell you much more than the story of Phailin.

(All figures are taken from Census data 2011, India Human Development report 2011-Towards Social Inclusion and BRGF, Ministry of Finance)