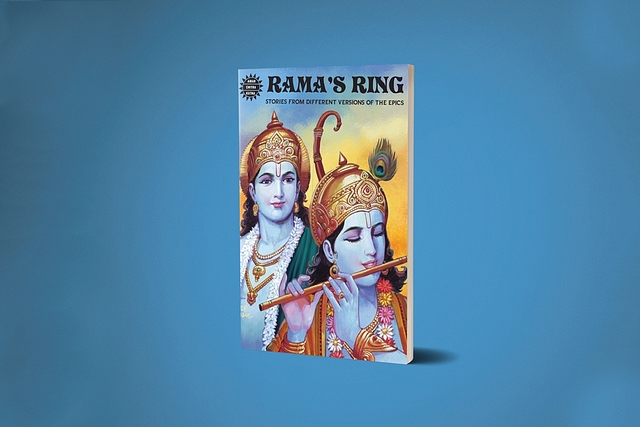

Amar Chitra Katha Continues Anant Pai’s Glorious Tradition With Its Latest Issue, ‘Rama’s Ring’

This issue introduces children to the diversity of epic traditions that exist in India and also to the multi-dimensional nature of every character.

Rama’s Ring: Stories From Different Versions Of The Epic. Amar Chitra Katha. Pages 72. Rs 199.

A few years back I attended a Hindutva conference. One of the speakers whom I will not name, was speaking against a particular book introduced in an undergraduate course.

As the speaker listed the ‘errors’ in the book, one of the ‘errors’ caught my attention. “Sita was the daughter of Ravana. So informs one of the stories of this book,” the speaker told the audience and the audience burst into laughter.

Unfortunately, I could not join that derisive laughter because I was familiar with this version and this was indeed popular in South India.

In this version, Sita was Ravana’s daughter but a divine voice proclaimed during her birth that she would be the cause of Lanka’s destruction.

So, with a heavy heart, Ravana arranged for Sita to be put in a golden basket, which would eventually reach the hand of Janaka.

Ravana was secretly monitoring Sita. Like all father-in-laws, he was also doubtful if Rama was really worthy of his daughter.

So he abducted Sita because he did not want his daughter to suffer in the forest and also to see if his son-in-law would cross all barriers and fight the battle. So the story goes.

It is a folk rendering where the Indian mind does not want to make anyone a villain and attributes a noble motive even to Ravana.

However, present the story as ‘Sita, daughter of Ravana’ and you have your shock value and an audience enthralled.

We need to tell the Hindu generation of the present day that there are indeed various versions and folk renderings of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and --- while not all have the same quality --- they all show the way India has absorbed the epics into its very being as a nation.

If we do not do that then forces with ulterior motives would do it --- not to praise the diversity but to injure the national spirit.

The Amar Chitra Katha (ACK) in its latest release has taken up this task of telling the young minds the way both Ramayana and Mahabharata have been enriched by each part of India in its own way.

Titled ‘Rama’s Ring’ and published this Deepavali, the book has 72 pages and nine stories derived from different versions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata from different parts and communities of India.

The first story, Rama’s Ring, is said to be from Central India. Actually it has its variants all over India. It also has a science-fiction touch to it.

Hanuman finds out that there are infinite number of Ramas and infinte number of Ramayanas happening. It is a very good starting point to introduce the concept of countless cycles of time to children.

While in the version given in the ACK, the moral of the story is to make Hanuman realise that the natural cycle of the present Rama should end, in the case of the Tamil variant, the goal is to remove even the slightest of pride from entering the mind of Hanuman.

The second story is said to be from the 15th century Odiya Ramayana by poet Sarala Das. Actually the work comes from Adbhuta Ramayana (attributed to Valmiki but a very later work with a clear Shakthic rendering of the epic --- particularly the aftermath of the slaying of Ravana).

Here, from the dead body of Ravana emerges a more demonic form with a thousand heads. In the comic, Sugriva and Hanuman say that Sita would know the secrets of Ravana and hence she should be summoned.

In the Adbhuta Ramayana, Sita is none other than Shivaa --- the Goddess inside all existence, including Shiva. So, she assumes the fierce form that kills the demon and then becomes the ferocious Kali and reveals herself to be so to Rama.

One could say that the comic creators missed an opportunity to present a great scene here.

The third story gives a Puranic background to Nagapasa --- the serpent-binders that Indrajit wields against Rama and Lakshmana with considerable success --- that immobilise the two heroes.

Garuda appears and releases them from the Nagapasa. The story is attributed to Kamban though in the main Kamban epic one cannot find this reference.

The fourth is about the killing of Indrajit, again taken from Kamban’s Ramayana.

The fifth story is from the Gond-Bhil communities. Here, the Ramayana and Mahabharata characters have a cross over. Bhima is called to rescue Lakshmana when Indra’s daughter Indrakamini abducts him by transforming him into a ram. The story is quite fascinating.

The one-sided love of Indrakamini ends in disaster with her being trapped in Lakshmana’s palace by Narada and the story ends enigmatically thus: ‘Some people of Bhil community believe that even today, on a dark night, they can hear Indrakamini screaming to be let out.’

Then there is the story of Sahadeva making Sri Krishna devotion-bound and immobile. The story is attributed to folk legends of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, and is fairly well known throughout India.

It shows the power a devotee has over the divine --- a unique Indian understanding of the relation between the devotee and his or her beloved Devata.

The seventh story has a different style of illustration and is from the Bhil Mahabharata.

Here the emphasis is on the real nature of Draupadi, who is worshiped as Shakti, as she reveals her true form.

The emphasis on the divine feminine actually adds a whole new dimension to the way we look at the epic.

These ‘folk versions’ actually aid in the understanding of the epics of Vyasa and Valmiki in a way that adds even more beauty and dimensions to them. All this, without being in any way contrary to the core spirit of the epics.

The eighth story is supposedly from a Tamil folk version of the disrobing and subsequent saving of Draupadi’s honour. Of all the stories assembled, this seems to be the weakest.

A rational explanation is given with a superficial feminist touch. Having lived all my life in Tamil Nadu and also having seen quite a few village theatre versions of the aforesaid episode, I should say I have never seen this version.

It reads more like a cooked-up story of a mediocre scriptwriter than a genuine folk traditional version.

The ninth story is quite interesting. Here the anxious and doubt-ridden Duryodana scripts his own doom by being over doubtful of Bhishma. However, the story also brings out an admirable quality in Duryodana: adherence to his words despite knowing well that such adherence would result in his defeat.

On the whole, the book is a treat. It introduces children to the diversity of epic traditions that exist in India and also to the multi-dimensional nature of every character.

This will lead children to understand their culture with depth and clarity and also to rise above simple categorisations of everyday life.

Brilliantly illustrated, this ACK issue continues the legacy of ‘Uncle Pai’.

The fact sheets on Ramayana and Mahabharata in between the stories add more beauty and value. A must-read not only for children but also for the adults who love Indian culture.