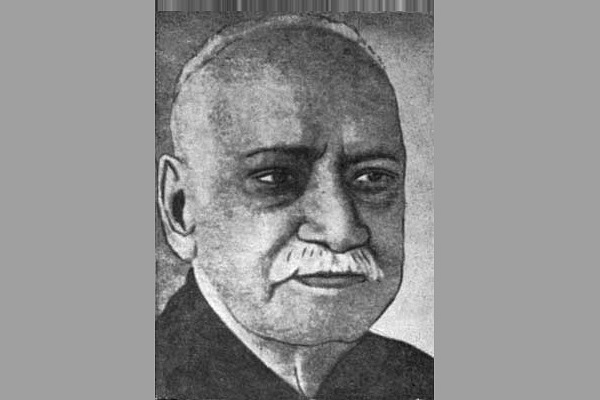

What Influenced Jadunath Sarkar's Idea Of India?

Sir Jadunath Sarkar was considered one of the greatest Indian historians of his generation. Dipesh Chakrabarty delves into Sarkar’s contribution in the shaping of history as an academic discipline in India, and why he grounded Mughal history the way he did.

It is true, as some modern historians have complained, that (Jadunath) Sarkar’s patriotic voice—the voice of “the true son of India”—is sometimes hard to distinguish from other kinds of patriotism that may have been actually present in the eighteenth century. Thus, when Mirza Muhammad Shafi, a mir bakshi (army minister) to the emperor and “the last fighting army chief of the empire”, was slain through “the blackest treachery” by Muhammad Beg Hamadani, a Mughalia sardar (chief), on 23 September 1783, Sarkar has the Maratha envoy “aptly describing” the situation: “Muhammad Shafi is dead. All Hindustan is lying bare. No sword for fighting is left in India.”

But Sarkar is also being a ventriloquist here. The deliberate mixing of his authorial voice with that of the Maratha envoy produces a cultivated ambiguity, but the two types of patriotism can be analytically separated. The Maratha envoy’s anguish would not have been tied in any way to a modern sense of, or a desire for, the nation. But then again, we would also be aware of the ambiguity of the word nation that allowed Sarkar to thus mix up sentiments belonging to very different historical periods. He would say of the “Jat state” during the “prudent reigns of Badan Singh and Suraj Mal” that its prospects of enjoying “a period of peaceful recuperation and progress” were destroyed by factors internal to the community: “A nation’s greatest enemy is within, not without.” Similarly, “internal quarrels and lack of statesmanship and even of intelligent self-interest among their leaders …so often ruined the national cause of the Marathas.”

It is such ambiguous use of the word nation that leaves Sarkar vulnerable to the charge of anachronism: did the Marathas themselves think of a “national cause”, or was it national only in the eyes of the beholder? But that ambiguity should not blind us to the fact that much of Sarkar’s lifelong absorption in Mughal, Maratha and Rajput histories was devoted to a quest for a measure of the potential India had for creating from within pre-British history a united and modern nationhood…The fall of the Mughal empire was a tragedy for Sarkar because, in his view—and here Sarkar sounds a little like our contemporary ‘early modernists’—the Mughals laid the initial groundwork needed to make India into a modern nation-state and yet failed to push the process to its logical conclusion.

The 1932 foreword to the first edition of the first volume of Fall of the Mughal Empire described that empire as having “broke[n] down the isolation of the provinces and the barrier between India and the outer world, and [having] thus [taken]…the first step necessary for the modernisation of India and the growth of an Indian nationality in some distant future”. “It must be admitted,” he wrote as he brought his multi-volume Fall to a conclusion, “that the Mughal emperors united many provinces of India into one political unit, with uniformity of official language, administrative machinery, coinage and public service, and indeed a common type of civilisation for the higher classes. They also recognised it as a duty to preserve peace and the reign of law throughout their dominions.”

Yet the Mughals missed their chances through Aurangzeb’s orthodoxy, which was followed by a series of inept rulers in the eighteenth century. Sarkar’s idea of the fall of the Mughals as a national tragedy makes no sense until we see him as a votary of some kind of “modernity”—an economically and politically united nation-state that advances education, welfare, and science for all. What was remarkable for Sarkar about the Mughals was that it was their rule that initially prepared the country for a movement in this direction:

Administrative and cultural uniformity was given to nearly the whole of this continent of a country; the artery roads were made safe for the trader and the traveler; the economic resources of the land were developed; and a profitable intercourse was opened with the outer world. With peace, wealth and enlightened Court patronage, came a new cultivation of the Indian mind and advance of Indian literature, painting, architecture and handicrafts, which raised this land once again to the front rank of the civilised world. Even the formation of an Indian nation did not seem an impossible dream.

Yet, Sarkar wrote at the end of his study of Aurangzeb-

Aurangzeb did not attempt such an ideal [of nation-making], even though his subjects formed a very composite population…and he had no European rivals hungrily watching to destroy his kingdom. On the contrary, he deliberately undid the beginnings of…a national and rational policy which Akbar had set on foot.” Akbar had successfully converted “a military monarchy into a national state”—not constitutionally but in effect—by remaining open both to talents of the Hindu Rajputs and to the “right type of recruits” from among the fortune seekers who came from Bukhara and Khurasan, Iran and Arabia.

Aurangzeb in particular failed precisely on this score. Whereas the “liberal Akbar, the self-indulgent Jahangir, and the cultured Shah Jahan had welcomed Shias in their camps and courts and given them the highest offices, especially in the secretariat and revenue administration”, the “orthodox Aurangzeb…barely tolerated them as a necessary evil”. The latter’s conflict with the Rajputs and “the hated poll-tax (jaziya) lent Shivaji the aura of a Hindu “national” leader in the eyes of his contemporaries. Sarkar wrote:

To the Rajputs and Bundelas, who had so long been the staunchest supports of the Mughal cause, the Mahratta hero [Shivaji] appeared as their heaven-born deliverer, — a Rama slaying Ravana or a Krishna slaying Kansa. This feeling breathes in every line of the Hindu poet Bhushan’s numberless odes on Shivaji.

Sarkar then makes “Bhushan kavi” (as he was known) speak for all Hindus-

He really voices in smooth and vigorous numbers the unspoken thoughts of the millions of Hindus all over India. At the end of the 17th century they had come to regard the Mughal Government as Satanic and refused to co-operate.

Thus, to revert once again to the prose of the Fall, a “natural progress” toward nationhood “was arrested”, and “after a quarter century of heroic struggle by that monarch”, decline “had unmistakably set in”. Sarkar restated his disappointment in the Mughals in what he added to William Irvine’s Later Mughals when he edited the book for publication in the 1920s:

The profuse bounty of Nature to this country, its temperate climate which reduces human want, and the abstemious habits of its people, all combined to increase the national income of India in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries…The wealth of Ind[ia] was the wonder and envy of other nations. But the Mughal court and Mughal aristocracy had not the sense to insure this wealth by spending a sufficient portion of it on efficient national defence and the improvement of people’s intellect and character by a wise system of public education.

So what was the ideal state the Mughals might have created? Sarkar’s ideals were all derived from the professed ideals of the British Empire. These ideals, it has to be remembered, were valued by many members of the intelligentsia—not all of them Western-educated—in the India of the nineteenth century in which Sarkar grew up. They came to be questioned in the twentieth century as a new and vigorous anti-imperial nationalism gained ground in India. Thus, securing unity and peace, that is, order for the population was in Sarkar’s eyes the sine qua non of good government.

The years 1754-1772, covered in the second volume of his Fall, saw the Afghans and the Marathas vie for Delhi and the Jats “forming a kingdom within the space of a decade”. But this was also a period when emperors were in turn deposed, banished, blinded, and murdered. But as the narrative got close to the end of the period, “the worst [was] over,” commented Sarkar, “and we begin to emerge into light”. What was this “light”? It had to do with the securing of peace and order.

Excerpted from The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of Truth (Permanent Black, Rs 795)