How The Sports Film Genre In Hindi Cinema Has Finally Come of Age

Starting with the lesser known ‘All Rounder’ in 1984 and reaching ‘Dangal’ last year, here is the story of sports films in India

The real drama in films as eloquently described by Frank Capra is not when the actors cried. Rather the true success of drama in cinema is when the audience cries as it reveals the extent of a viewer’s investment. The one genre where this emotion could be experienced the most, unfortunately enough, also happens to be the one that up until recently had been largely ignored. Sports in Indian and especially popular Hindi films had been waved aside for a long time and moreover have not been treated with the same respect as other genres. Yet the influence of the genre cannot be undermined. It is a testimony of the impact that the popular film template wields as well as what it can achieve that the legendary athlete Milkha Singh reportedly charged one rupee as fee from Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra to tell the world his story in Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013).

One of the reasons for the sports film to not get the same prominence as other genres could be the manner in which they build their narrative. The genre predominantly has two kinds of format - one where the narrative pivots around sports (Chak De! India, Sultan) and the other where the narrative initially appears to cast a glance at sports but merges the activity with a bigger social, political or cultural phenomenon (Lagaan, Dangal). Unlike other genres, because the sports film addresses wider issues in an oblique fashion, the ramifications, too, then have a greater indirect impact.

This could possibly be the reason why the genre is not taken as seriously. The tax-free status awarded to Dangal, wrestler Mahavir Singh Phogat (Aamir Khan) trains his daughters Geeta and Babita to become world-class wrestlers is not its greatest success. Even the interest shown by the government of Haryana, a state that has perhaps produced the most successful wrestlers in India, to award equipment such as mats to the akharas and promoting the sport amongst girls is also not one. But the likelihood of girls being seen as a catalyst for change, however, symbolic it might truly be, is probably the biggest triumph of the film.

An Olympic medal saw Sakshi Malik become the brand ambassador for the Girl Child campaign in Haryana where sex ratio crossed 900 girls to 1000 boys for the first time in a decade. Similarly, post-Dangal a change on the ground can be seen with developments such as parents becoming aware of the sport and nurturing dreams of their daughters achieving what the Phogat sisters managed. In Jammu, 37-year-old Ritika Salathia, the first woman to represent Jammu & Kashmir in wrestling, has seen a surge in the interest in wrestling after Dangal among girls and has been working overtime in her coaching camp.

For a long time sports by itself was not treated with the same respect as other activities or vocations in India. It was only natural for films based on sports to also suffer a similar fate. It is telling that even with having witnessed the brilliance of a hockey wizard such as Major Dhyan Chand, considered to be one of the greatest players ever to grace the game, there was never a film made on him. At the 1936 Berlin Olympics Adolf Hitler even tried to lure the army man to migrate to Germany but Dhyan Chand refused. At the same Olympics, the achievements of a Jesse Owens, who was also offered a similar post by Hitler, and who, like Major Dhyan Chand passed on the offer, went on to inspire millions and his story was celebrated in popular literature. In the same way, sprinter Milkha Singh and boxer Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, achieved sporting glory at the same summer Olympics of 1960 that were held in Rome but again their presence in popular culture is far from same. Unlike Clay, who never competed in the Olympics again, Milkha set a world record in 400 metres when he clocked 45.8 seconds in one of the preliminaries in France and even though he came fourth in the finals at Rome his timing of 45.6 seconds remained a National Record in India till the 2004 Athens Olympics.

Some of the first sports films that were made in India focused on cricket that had become very popular following India’s surprise win at the 1983 Prudential World Cup. The underdogs thwarting the ruling champions of the world, the West Indies, was the stuff of dreams but the early films that tried to capture this essence of the game failed miserably. Mohan Kumar’s All Rounder (1984) with Kumar Gaurav playing an underprivileged but talented all-rounder who manages to sport the Indian cap did not click with the viewers. The same year also saw the release of Hip, Hip, Hurray (1984) that used sports namely football, both as a direct as well as an indirect metaphor for broader themes. The story of youthful rebellion and angst where a temporary sports coach (Raj Kiran) has to deal with a young student (Nikhil Bhagat) who is bursting with hormones and can tip over if not dealt with sensitivity as well as sensibility remains one of the best sports films in India. It was around the same time that Anil Kapoor’s Saheb (1985) where he played a promising football goalkeeper who gives up on his dream in order to support his family released and while the film did much better than All Rounder the element of sports was minimal.

Towards the end of the 1980s, there were many young sports persons on the anvil. This was also the time when a P.T. Usha had come to become the embodiment of achieving the impossible through sheer hard work. Yet she or the arrival of a V. Anand, a Leander Paes, and a Geet Sethi could not challenge cricket’s popularity. But that did not mean that the cricket films that followed became a resounding success. Films such as Awwal Number (1990) where the chairman of cricket selectors (Dev Anand), who is also a former police commissioner, has to stop his star cricketer brother (Aditya Pancholi) from teaming up with an LTTE like outfit in a fit of rage for losing his spot to an up and coming player (Aamir Khan) was a lot about cricket and at the same time fell short of capturing the essence of the game or the men who played. The failure of Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar (1992), where a cycle race becomes much more than a mere sporting event put Bollywood off the genre for a long time.

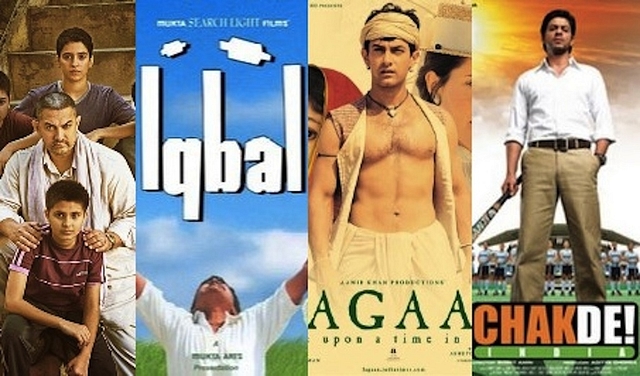

The concept of sports films in popular Hindi cinema underwent a tremendous transformation in the last decade and a half, thanks to Lagaan (2002) and Chak De! India (2007). The former was perhaps the earliest of the first so-called sports films that truly highlighted the hybridity of popular Hindi films by taking a concept such as a cricket match between Englishmen and Indian villagers in the late 19th century and merging it with a much larger theme that included elements of race, nation, religion and caste in its story. The success of Lagaan made Indian cinema one of the chief sources of fictional cricket films in the world – Iqbal (2005), Stumped (2003), Say Salaam India (2007), Victory (2009), Hattrick (2007), the Tamil ‘street cricket’ film Chennai 60028 (2007), 99 (2009), Jannat (2008) Dil Bole Hadipaa! (2009), Victory (2009), Patiala House (2011) to name a few.

Chak De! India also in many ways proved that a sports film can be much more than a genre film and unlike Lagaan had a mix of a larger than life overarching theme of nationalism and individual tales of redemption.

More than the sports film coming of age via greater depiction of sports or sports persons it was also the emergence of the biopic genre that changed the fortunes of the sports film. The recent success of films like Mary Kom (2014), Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, MS Dhoni: The Untold Story (2016) and now Dangal is testimony that the viewer is aching for more sports films. Even if creative liberties threaten the narrative’s authenticity, for instance in Mary Kom where instead of an actor from Manipur, the state where Mary Kom hails from, a Priyanka Chopra was cast as Mary Kom, or in Dangal where Mahavir Singh Phogat was shown to be locked inside a room when his daughter was competing even though in reality he was by the ringside or the omission of M.S. Dhoni’s elder brother from the biopic based on the cricketer’s life, the audience has chosen to overlook it. The fact that much like all great cinema these films also draw on emotions that might not be wholly rational but celebrate a moment of unity created by sporting success that is also nationalistic at times, and the viewer being intelligent enough to know the symbolism and look at the bigger message shows true acceptance of the sports film.

It is this that saw the same audience brush away a whitewashing of history in Azhar (2016), the film based on the life of disgraced former cricket captain Md. Azharrudin in the same year when it hailed MS Dhoni: The Untold Story, Dangal, and Sultan.

The manner, in which Hindi films have managed to strike a chord between messaging and entertainment without trading the essentials of the universe that it operates within, shows that the time is ripe for a biopic of Sania Mirza, Sakshi Malik, Vijender Singh and P. Gopichand to name a few. The troubles undertaken by young aspirants and the hardships of Ranji players as mentioned in Akash Chopra’s book Out of the Blue or the stories in Shamya Dasgupta’s Bhiwani Junction- The Untold Story of Boxing in India that show how young boys prone to picking a life of crime instead opted for boxing thanks to Vijender Singh’s bronze medal in Beijing Olympics or the singular tale of Tajamul Islam, an eight-year-old girl from the rugged village in terror inflicted Bandipora district in J&K, who won the gold medal at the World Kickboxing Championship in the sub-junior category are great films waiting to be made.