How To Loot Indian Temples: A Step-By-Step Guide To Steal Precious Antique Idols

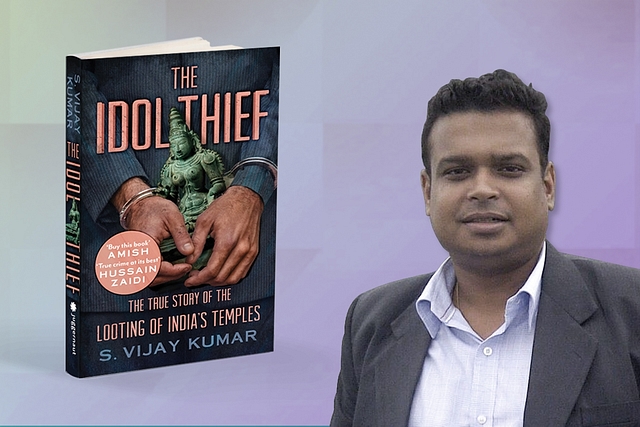

S Vijay Kumar’s book, ‘The Idol Thief: The True Story Of The Looting Of India’s Temples’, is a detailed and bare-all account of of all that’s bleeding Indian heritage.

If you have ever visited an ancient temple and felt saddened at the missing idols or the stolen bronzes and wondered how something so precious and ancient could be stolen from ‘protected’ sites, here is a step-by-step procedure followed by the one who supplied the ‘missing’ antiques to the one of world’s most notorious ‘art dealer’ Subhash Kapoor.

Kapoor had been pillaging India’s temples through a well-oiled network of complicit officers, museum officials, local temple idol smugglers, and some erudite academics. And the myth of ‘art dealing’ was busted when he was detained in Germany in 2011 for art theft.

He was extradited to India in 2011.His arrest led to the recovery of Indian art worth $100 million. Kapoor, ‘one of the most prolific commodities smugglers in the world’ as he was named by the United States authorities, was helped by Sanjeevi Asokan, another ‘art dealer’ based in Chennai who smuggled the idols out of Chennai.

S Vijay Kumar’s book, ‘The Idol Thief: The True Story Of The Looting Of India’s Temples’, is an account of of all that’s bleeding Indian heritage, one idol at a time. A Singapore-based finance and shipping expert, Kumar has been tracking these notorious Idol thieves for years and continues to do so. And in his book which will be launched today, he has narrated the tale of the most painful yet sadly on-going plunder of India’s temple treasures. Here is an excerpt:

Sanjeevi’s modus operandi was similar. However, of late he had been riding high on confi dence and the complicity of more flexible officials meant that he just shipped the original antique instead of even bothering to hide it among fakes. Sanjeevi showed how easily this could be done when he shipped a Nataraja, an Uma and a Ganesha in May 2006.

The container freight station in north Chennai is where containers – the enormous steel boxes used in shipping – are loaded and then transported to the port. Even at night, it is always humid, dirty and hot. It was worse that May, when the famed Chennai heat coupled with power cuts to drive temperatures and tempers even higher. It was past 9 p.m., yet the area around the government loading facility was still teaming with activity, and the roadside eateries were dishing out an assortment of biryanis and chilli dosas. Since movement of container trucks inside city limits during the day was not allowed, they lined the roads for several kilometres at this time in a serpentine queue to pick up the loaded containers to transport them to the port. The shipping clerks, responsible for seeing through their employers’ outgoing shipments, with their paper folders carrying an assortment of invoices, packing lists and shipping bills, rushed to the customs desk to get their shipping bills (mandatory documents to be fi led by the exporter) passed.

It was a task so routine for the customs clerk, the government official who ensures all the paperwork for export is in order, that he hardly ever read through the contents of the bills presented to him. He had to just check on his computer screen if the shipping bill number showed up as assessed. The assessment takes place earlier at the customs head office, opposite the port, where they had already entered the exporter’s name, commodity, packages and decided if the price mentioned in the shipping bill was reasonable for the commodity being shipped. The customs clerk’s job was the next and most vital step – examination, which technically meant he had to randomly pick a bill and physically go and examine the cargo to see if it actually matched the items listed in the shipping bill. In reality, he got up only three times during a shift – once for coff9ee and twice for his cigarette.

His hand stamped the red ‘Examined’ endorsement mechanically on every twentieth copy, and ‘Let Export’ on every shipping bill. Th e bills he cleared went into a huge box. He had to clear 250 such shipping bills every shift. A little inducement to bring the stamp down on the paperwork always helped him work faster, more cheerfully. So much for checks!

Sanjeevi’s man (he cannot be named for operational secrecy reasons) took out his already soaked handkerchief to wipe the sweat on his forehead. He had argued with his boss that the risks were too high. Sanjeevi planned to send the idols as a loose shipment, not in a private container, which meant the crates containing the idols would be given to a shipping company as stand-alone items at a public loading area within the customs premises. The stakes were enormous as there are at least half a dozen other containers being loaded at the same time with over a hundred labourers and over a dozen customs officials hovering around. If something were to go wrong it would happen in front of everyone. A private container on the other hand could be loaded at Sanjeevi’s warehouse, with a single customs officer watching – fewer people to ‘manage’. He had pleaded with Sanjeevi to wait for a few months and collect more ‘orders’ and ship out as a full container so that they could bring the container to their godown. But his boss wouldn’t listen. He had instructed him to wait till 9 p.m., which is when the customs officials changed shifts, and then tell him who was at the desk. His man called with the name. There would be no problem. He told him to proceed.

Sanjeevi’s man looked at the documents once again. There were three items listed as ‘Indian Handmade Artistic Handicraft Items’ worth $1,500, which included $150 for the mandatory insurance. He checked again. There were three roughly nailed wooden crates – he had been with them on the truck from Mamallapuram, the sleepy Pallava heritage town, 65 km from Chennai. Though the documents listed the gross weight of the entire shipment as 225 kg, his boss had insisted he use a 3-tonne forklift to offload the crates from the truck and stack them in the loading yard. Not for any other reason than that he simply couldn’t afford an accident such as the forklift dropping the crates in front of everyone and revealing their contents. All sides of the crates were marked ‘Fragile’. He looked into the description once again and swallowed hard. He wanted no mishaps during the loading as there would be at least ten other men looking on to ensure their shipments were loaded safely into the same container.

Earlier in the morning, it had been a cakewalk at the central customs office when the shipping bill was assessed. He was tense there as well, as the price on the invoice was much lower than even for poor quality steel, and this was bronze. Yet, his boss had been confident. He had all the necessary paperwork ready, including the faded blue colour photocopy of the certificate from the handicrafts promotion body. His boss had given him two envelopes, one marked P (photos) and the other unmarked. The officer sitting across the large wooden desk seemed to know which one to open. He took the one marked P and shook out the contents. Five grainy photos of Shiva as Nataraja, Uma and Ganesha fell on to the table. The other, fatter, envelope went right into the drawer. The same drawer yielded an assortment of blue and red seals and stamps, which he proceeded to put on the bills.

Now, in the evening, he had to get the shipping bill passed by the customs clerk. He needed the critical ‘Let Export’ stamp. The assessed shipping bill went, neatly tagged with twine, to the desk. The officer seemed irritated with the non-functional table fan as he saw the bunch of documents. There were no fat envelopes here. The shipping clerk called his boss and passed the phone to the customs officer. Into the phone, the officer said a four-digit number. Outside the customs facility, a Yamaha stopped near an auto, checked the licence plate – it had the same number that the customs officer had just said into the phone – and passed on a dirty bundle crudely wrapped in an old newspaper to the auto driver. The auto driver made a phone call to the same customs officer who then put the stamp, leaving a blue and a red barely legible stain on the paper and scribbled over it, ‘Examined’, ‘Let Export’.

Excerpted from ‘The Idol Thief: The True Story Of The Looting Of India’s Temples’

by S Vijay Kumar , Juggernaut, 2018, with the permission of the publisher.