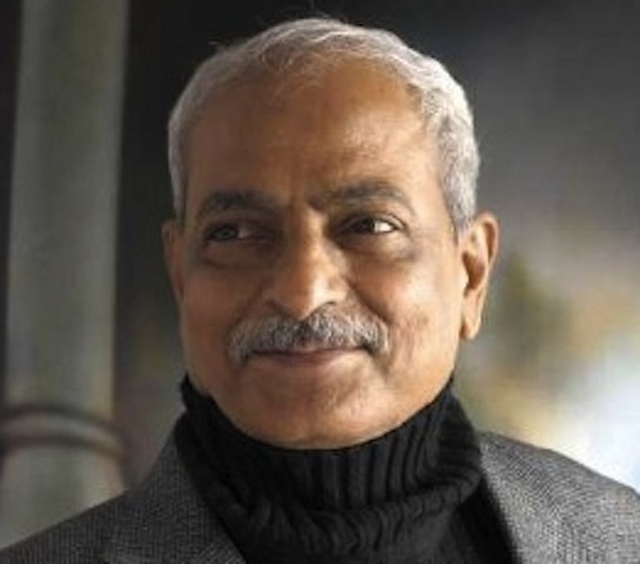

Mahesh Elkunchwar: Where Silence Speaks More Than Words

One of the few writers who have become eminently successful despite maintaining an almost zeal-like passion for avoiding commercial pressures is the Marathi playwright Mahesh Elkunchwar.

Elkunchwar is one of the finest Marathi writers with more than 20 plays to his name, in addition to his theoretical writings, critical works, and his active work in India’s Parallel Cinema as actor and screenwriter. He is, today, along with Vijay Tendulkar, one of the most influential and progressive playwrights in Marathi theatre.

In fact, Mahesh Elkunchwar owes it in some way to Vijay Tendulkar to start his journey in writing plays. It happened by chance when, almost 50 years ago, he could not get a ticket for a film and landed up seeing a play by Tendulkar.It soon becomes a vocation, leading to a prolific output like Garbo, Raktapushp, Party, Pratibimb, Atmakatha, amongst others. Apart from Tendulkar, he has also been influenced by a number of Western authors like Anton Chekov, Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus.

Elkunchwar is a self-conscious modernist, not a hoary traditionalist. A strong votary of urban Marathi theatre, he looks upon all forms of folk theatre as, in his own words, ‘instances of artistic kleptomania’. Elkunchwar came into the picture when bold experimentation was becoming popular and many plays like Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug, Mohan Rakesh’s Ashad Ka Ek Din and Adhe Adhure continued to push the boundaries of Hindi theatre. It was also the time Vijay Tendulkar’s plays were hitting the Marathi middle class and its hypocrisies where it hurt the most. His plays, while being socially relevant, spoke against the middle-class ennui in grappling with its own hypocrisies. Unlike Tendulkar, Elkunchwar did not use violence; his was a more suppressed attack, but it hurt more.

Girish Karnad, who translated and directed many of his plays into Kannada, says of Elkunchwar’s style:

‘What sets Mahesh apart among Indian playwrights is his command of the broken phrase, the sentence half-uttered, the casual pause—in his hands these silences can be lethal and communicate a menace that would be scattered in a collection of fully expressive sentences. Every time I have taken on a text of his, I have enjoyed the crispness of sentences often left cliff-hanging, the deliberate avoidance of a direct reply, and the poignancy created by any direct verbal contact. His plays are resonant with the dhwani (sound) of the words he has chosen to use or throw away.’

Elkunchwar says, of his own approach, ‘When I intend a pause in a dialogue, every pause has its duration and every actor should know this. In my first play, I used to refer to counts. But then I realized that the director never follows this and I gave it up. Yet, I mark the pauses so that the readers should know. Pause can give a complexity to dialogues and actors should use them more than words to reach out to the audience.’

Elkunchwar’s plays are not autobiographical, but they reflect the loneliness he faced as a college student. The image of darkness dominates most of Elkunchwar’s plays. It is not just the physical darkness, but it is the all-pervading darkness, occupying the psyche and the future of the characters. Yatanaghar is a glaring example of it. Most of the times, the sequence of events leads to a disastrous end. Whatever his theme or mode, Elkunchwar’s plays are marked by his mastery over dramatic structure, each play having a well-defined beginning, middle and end. His language, which began as an unstoppable outpouring in his early plays, quietened down later to an economic, rhythmic prose, full of eloquent silences.

Both critics and audiences agree that Elkunchwar is one of the few playwrights who can probe the human mind and actually sift through thought processes and emotions to create a tapestry of interlinked responses and situations.

The playwright, who was once a professor of English at Nagpur’s Dharampeth College and has also taught at the Film & Television Institute of India for a while says:

‘I have somehow never been interested in the externalities. It is the journey into the interior of the mind that has been an obsession with me. It is difficult to say why I keep travelling to the interior but, perhaps it has to do with the fact that the life we see around us is transient and does not give my creative instincts a call. The process that is internal is, however, more permanent and unchanging, and flows steadily below the effervescent reality. It is the inner landscape that provides clues to this mystery called life.’

Unlike others, Elkunchwar is not moved to let his words be a reflection of the socio-political or cultural changes that unfold around him. Nor does he let his personal misgivings or anger about various issues seep into his plays.

Of all his plays, the one that resonates the most, and the one with which he is associated most, is Wada Chirebandi, which Vijaya Mehta later directed, and which has been staged in several Indian languages since its launch. The playwright says that ‘Wada is not a simple family drama; it is more than that- a document of social and political change.’

Wada deals with a whole age; showing gently if firmly the slow decline in the fortunes of a traditional Hindu family, as it comes to terms with the demands of modernity. The pain is muted and therefore searing. Indeed, for many critics, dramatists, and fans of his work, that play remains his seminal work. The playwright was born in an old house, just like the wada in the play. His father was a landlord, but his brothers and he left the house to seek a different life. The wadas nearby were all crumbling. There was a sense of inevitability, lethargy, and a resistance to change.

Like Mohan Rakesh in Hindi and Badal Sircar in Bengali, Elkunchwar has transcended the limits imposed on him by the confines and milieu of his language and geography. The rich tradition of translations and interpretations within Indian languages made his plays go further.

Bengaluru-based playwright and director Mahesh Dattani recalls the influence of Pratibimb, which he staged as a double bill with Raktapushp, a sensitive look at the mind of a menopausal woman who transferred the love for a son she had lost to a young paying guest. Dattani says Elkunchwar is important for many reasons, ‘primarily because he captures a society in transition. Like Chekhov, he too is fascinated by rural/feudal values and urban aspirations.’

Pratibimb takes a satirical look at the loss of an ordinary man’s identity in the anonymity of the urban jungle. One of his more accessible plays, Party, concerns itself with the question of art versus action while observing the irony and hypocrisy of patrons of art. Elkunchwar satirized the artificial and suffocating veneer of sophistication.

Raktapushpa, written in 1971, is another celebrated play of Elkunchwar. In this play, the playwright explores the inner emotional universe of his characters. The Marathi as well as Hindi version of the play was staged by renowned experimental director Satyadev Dubey in the early eighties. With actors like Amrish Puri and Sunila Pradhan, the Hindi production had done full justice to Elkunchwar’s exploration of the female consciousness – one shaped by bodily changes (puberty to menopause) and their inevitable psychological effects.

The name Raktapushp has a correlation with the menstrual blood and the play makes a lot of references to the menstrual cycle, a subject considered taboo to be discussed in public.The play traces the journey of two women with different sexualities -a wife-cum-mother who is devoid of sex life and a daughter who has just begun exploring her sexuality. The two women, bound by laws of nature, raise some key issues about sex, the human power of creation and the basic question – whether a life devoid of sex signifies a death of some kind.

Sonata was penned by Mahesh Elkunchwar in the year 2000. The play revolves around three women who live non-conformist and unconventional lives – free and outrageous, but also lacking and lonely in some ways. Elkunchwar deals with these unmarried women with a lot of compassion.

The action takes place in one drawing room at one night. Three girlfriends share their innermost thoughts. They often hurt each other, knowingly and unknowingly. All three are very unlike each other – one is a prudent mature scholarly Maharashtrian, another food-loving, happy-go-lucky fat Bengali and the third one- an exceptionally, gregarious free spirit with quite an appetite for men. Despite their freedom and career achievements, none of these women is at peace with themselves. Elkunchwar subtly depicts the grief in the lives of so-called independent thinking women.

In Atmakatha (Autobiography) the characters in the play, Rajdhyaksha, Pradnya, Uttara form a romantic triumvirate. Raja is an eminent writer who is in the process of completing his autobiography, its authenticity under severe question. His ‘autobiography’ functions as an artificial mask to hide the controversies of his private life, especially his relationships with women.

Raja, married to Uttara earlier, indulges in an extra-marital conjugal relation with her sister Vasanti which breaks the Raja-Uttara-Vasanti family triangle apart. Raja is deserted by both the women and the relationship of the two sisters crumbles into fragments.Pradnya, a research scholar who as a part of her research, interviews Raja comes to know about the harsh, complicated realities about Raja‟s life. Raja admits that he has hidden several dark aspects of his personal life to save his social image. He also defends his process of lying with a truth which is actually virtual in nature. He believes that to be a successful fiction writer it is not possible to mention every element of truth.

Even the truth and reality of all the characters in this play is questioned on the basis of the various roles they play in different situation and time. The multi-layered features of every character are revealed through their dialogues. The attitude and the dialogues of the characters mismatch with the actual purpose of their action which are always transient in nature. The play shows that truth has no everlasting permanence and is an individual construct of a specific moment and situation.

Influencing the Indian theatre for more than three decades, Elkunchwar has experimented with many forms of dramatic expression, ranging from the realistic to symbolic, expressionist to absurd theatre with theme ranging from creativity to life, sterility to death.

Not many people are aware that his 1984 play, Holi, was made into a film by Ketan Mehta for which he wrote the screenplay too and another of his plays, Party, was made into a film by Govind Nihalani the same year. But the association with films did not go beyond the two mentioned above. ‘I have not exactly shied away from film scripts, but the truth is that no one approached me after my first two films. Also, what disturbs me is that a scriptwriter is a poor relative in films, an inevitable evil for most directors. His status is like that of a munshi and no self-respecting creative writer would like to fall to such a level. I might write a script if I decide to direct a film myself,’ he states.

An even lesser known fact about him is as an essayist. His collection of essays ‘Maunraag’ has broken new grounds in this genre and was considered the book of the decade in 2012. Maunraag is an uncanny blend of autobiographical and meditative and the essays show erudition and a vivid imagination.

Elkunchwar does not come into the category of ‘popular’ as he often dabbles into experimental theatre and does not socialize for the sake of being ‘seen.’He was, for a period of nearly eight years, not visible on the theatre scene and is considered a recluse by many. He wanted to replace the ‘shrillness’ with ‘substance’ he says.

‘Experimental theatre is a probe…a search for new ways to express new areas of human experience. An audience for such theatre is bound to be small. Always, anywhere in the world. There is no chance of trying anything for ‘effect’ here. You do that when you want to stun, please or woo your audience. In experimental theatre, it is a pure exchange between the audience and the actors or director, with no other trappings or expectations. There is a togetherness with the sole aim of finding something new.’

Elkunchwar believes it is his Wada trilogy (Wada Chirebandi, Magna Talyakathi and Yuganta) which will remain his most known work. No doubt Marathi stage is blessed to have such independent and creative writers which make the stage vibrant as it is. We need more such Elkunchwars!