Nine Indian Writers Who Should Have Won the Nobel

Since Tagore in 1913, no Indian has been awarded the Literature Nobel, though a few have been nominated. Here are nine people who Swarajya thinks should have won the prize. Please write in with your suggestions.

Rabindranath Tagore won the Nobel Prize for Literature in the year 1913. According to the award citation, Tagore had been chosen because of his “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse”, and for the way he had made his poetic thought “a part of the literature of the West”. Since its inception in 1901 and in the years prior to Tagore being honoured, the Literature prize had largely hovered around Sweden, selecting winners from countries such as France, Germany, Belgium, Norway and Italy (stepping out of the European mainland just once in 1907, for Rudyard Kipling). Tagore, in effect, became not just the first Indian but the first non-European to win the award.

In the little over 100 years since then, no other Indian has been awarded the Literature Nobel, though a few have been nominated. (Details about the nominations are kept secret for the first 50 years and then revealed on the official online database). Based on the data available for the years 1901-1964, Indians nominated for the Literature Nobel – apart from Tagore – include Roby Datta in 1916, Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (five times between 1933-37), Sri Aurobindo (1943), Bensadhar Majumdar (twice, 1937 and 1939) and philologist Sanjib Chaudhuri (twice, 1938-39).

Over time, the selection process itself has become mired in controversy. The Swedish Academy – an 18-member body that decides on the winner – has been repeatedly accused of a Eurocentric bias, and quite rightly so: who can remember what “new era in literature” had dawned because of Carl Gustaf Verner von Heidenstam, the Swede winner of the 1916 Nobel? Or why much later in 1974, Eyvind Johnson and Harry Martinson, both Swedish and joint winners that year, were judged more worthy by the Committee over Graham Greene, Vladimir Nabokov and Saul Bellow, also under consideration?

In his will, Alfred Nobel had made it clear that the Literature Nobel should be awarded to “the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”. That directive, conformed to the letter, has been used to justify many of the early omissions, including James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Henrik Ibsen or Anton Chekhov. That grip has loosened over the years. Nevertheless, the announcement of the Literature prize each year brings with it derisive scorn (especially by Americans, who have been overlooked since Toni Morrison in 1993 and remain quite peeved), some chest beating (the Koreans wonder why one of theirs can’t win it too, the English worry they are no longer the locus of the literary world) and a general introspection whether a group of Nordic people can really stand in judgment over vast and varied categories of writing from every corner of the earth.

Here at Swarajya, we stopped vexing about the present, for a while, to wonder which of our great writers, provided they were translated ably and on time, ought to have made the grade and deserved a Nobel. It is not an exhaustive list, nor is such an enterprise recommended in a country as richly multilingual as ours. But it might act as a kind of guide as to where to look, next time when you are looking for some gutsy writing:

1. Bibhutibhushan Bandhopadhyay (1894-1950)

It is difficult today to separate the aesthetic intensity of Pather Panchali the novel (1929) from the cinematic brilliance of its movie adaptation by Satyajit Ray (1955). Ray was struck by Pather Panchali for “its humanism, its lyricism, and its ring of truth”. In Pather Panchali and its sequel Aparajito, Bibhutibhushan had not only created a parable of rural Bengal, with its little joys and mighty sorrows but also a perfect Künstlerroman, charting the course of Apu’s life along with the growth of his artistic sensibility.

From a grim chronicle of the 1943 Bengal Famine in Ashani Sanket to the tender pathos of short stories like ‘Pui Macha’, Bibhutibhushan’s art fitted all the labels that a Nobel selector is supposed to look for.

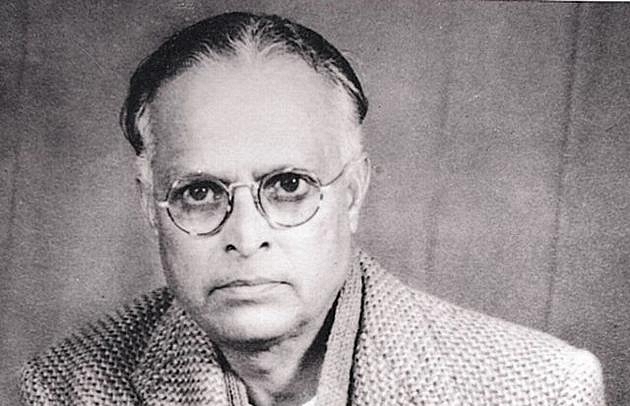

2. Munshi Premchand (1880-1936)

Born Dhanpat Rai, Premchand believed that writing was anchored in idealism, that writers served a social function. His stories of the rural poor are, therefore, not just detached observations but contain a powerful social critique as well. Schooled in both Urdu and Farsi, he started writing in Urdu, later moving towards Hindi, steering fiction in both languages away from the predilections towards romance and fantasy.

The exploitation of the rural poor and peasantry inform much of his novels and short stories though Rangbhumi (1925) and Godan (1936) tower above the rest. Whether it is the raw primal emotions in a short story like ‘Kafan’ or the decadent sensuality of Nawabi Lucknow in ‘Shatranj ke Khiladi’, Premchand was both master stylist and storyteller, and an obvious candidate for a Nobel.

3. Kuvempu (1904-1994)

KV Puttappa, better known as Kuvempu (an acronym of his name), was one of the greatest writers in Kannada. He began his career by composing verses in English but soon switched to Kannada, writing and experimenting, and importing aesthetic and stylistic elements into the language that were previously unheard of.

His lilting, lyrical poems express a love and veneration for nature that obviously drew inspiration from the English Romantic poets. But it’s Sri Ramayana Darshanam, his reimagining and reinterpretation of Valmiki’s Ramayana that is widely regarded as Kuvempu’s most important work, and which earned him the Sahitya Akademi award in 1955, the first ever for a Kannada language writer. It took nine years in the making, recasting characters and introducing new episodes, reviving interest in the epic, a genre that otherwise gets the short shrift among Nobel selectors.

4. Ismat Chughtai (1915-1991)

Calling Chughtai ‘the grand dame of Urdu writing in India’ – a somewhat insipid turn of phrase –obscures the fact that she was brave, spirited, uncompromising in life and work and an artist of the first order. Her narrative candour allowed her to talk about female sexuality, smashing the genteel and respectable veneer that surrounds such uncomfortable issues. While both Terhi Lakeer and Ziddi are remarkable instances of the feminist novel, it is the short story that was Chughtai’s forte. She used the medium to explore the socio-economic compulsions that limited women, in celebrated (and controversial) stories like ‘Lihaaf’ and ‘Chauthi ka Jorha’. It would be interesting to speculate though what the acerbic Chughtai would have thought of a Nobel.

5. RK Narayan (1906-2001)

On October 10, 2014, Google decided to honour RK Narayan on his 108th birthday with his very own doodle. The catch? The doodle was displayed only in India. It exposed the limits to how much a writer—even one like Narayan, who was more than once nominated for the Nobel – might remain localised, even after his death.

Narayan’s work, as it happens, can only be considered in its totality if one is to understand Malgudi, his mythical small town locale and the ordinary concerns that underlie the lives of its ordinary inhabitants. The pace of life at Malgudi might be slow, its intrigues mundane but as Graham Greene, who helped Narayan find a publisher noted, the stories have a “beauty and sadness” similar to what one might find in Chekhov.

6. Sundara Ramaswamy (1931-2005)

Ramaswamy, though Tamil-born, grew up knowing Malayalam, Sanskrit and English and formally learnt Tamil only when he was about 18 years old. Known for his poems, short stories as well as his critical essays, it is his novel, J.J: Sila Kurippugal or J.J: Some Jottings (1981) that is regarded as his outstanding work. Described variously by critics as an “anti-novel” or “ideas dressed up as literature”, it is the posthumous biography of a fictional Malayalam writer, his life and ideas as they become apparent from his diary jottings.

The novel parodies the Malayalam literary scene, with J.J attending his memorial meet only to hear a fellow woman writer comment that he would have won the Nobel had he written in English. Though not prolific, Su Ra pushed boundaries in both style and substance and was a master practitioner of the craft.

7. Ashapurna Devi (1909-1995)

In the absence of any formal education, Ashapurna Devi learnt to read and write by overhearing her brothers practise their lessons; her writings, like Jane Austen, are minutely etched portraits of the world she was familiar with, especially Bengali women in colonial and post-colonial India and their struggle for creative and intellectual emancipation.

That story is forcefully and poignantly told in the famed trilogy of Pratham Pratisruti or The First Promise (1964), Subarnalata (1967) and Bakulkatha or The Story of Bakul (1974). Satyabati is the protagonist of Pratham Pratisruti (her daughter and granddaughter of the sequels respectively) and to read about her spirited efforts as a child to read and write in defiance of society’s injunctions – her cousin brother reminds her that women who read turn blind and are promptly widowed – is to remember the road that Indian women have travelled in the last 100 years. If Toni Morrison could win a Nobel for grasping “an essential aspect” of reality, so could Ashapurna.

8. Vaikom Muhammad Basheer

(1908-1994): Basheer, or the Beypore Sultan as he was commonly known, was notoriously difficult to translate, given his ear for the colloquial tongue and his apparent disregard of the rules of grammar. His insight into human behaviour was robust though the analysis and critique was often softened by the use of humour, satire and sarcasm.

Primarily known for his novels and short stories, Basheer was frequently autobiographical, delving into his own life for material, the best example of which is Balyakalasakhi or The Childhood Companion (1944), a romantic tragedy considered to be his best work. Also well known are the humorous novels, Premalekhanam or The Love Letter (1943), his first work to be published as a book and written while he was in prison, and Pathummayude Aadu or Pathumma’s Goat (1959).

9. Amrita Pritam (1919-2005)

The first woman recipient of the Sahitya Akademi award in 1956, Pritam wrote in Punjabi and Hindi, and her more famous work deal with the horrors of the Partition, the one incident that tore apart her own life, society and the nation.

Born in Gujranwala in undivided Punjab, she had migrated from Lahore to India; Ode to Waris Shah, one of her best known works, is an invocation in the context of the massacres that accompanied the Partition. But it is not just the times that find reflection in her work but her remarkable insight into human character, most notable in her novel Pinjar (1950) as well as in many of her short stories. If the artistic expression of a human tragedy on an unprecedented scale ever needed attention, you wouldn’t have to look past Pritam.