On Dharampal’s Birth Anniversary: Short Descriptions Of The Gandhian Scholar’s Most Important Works

On his birth centenary, it is important for us to bring Dharampal back to the centre of discussion.

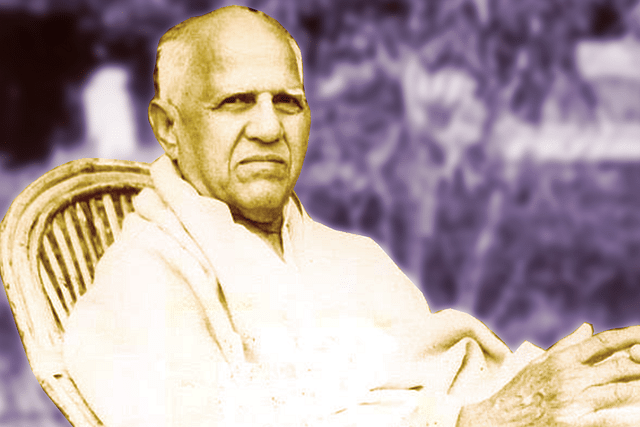

Born on 19 February 1922 in Kandhla in Uttar Pradesh’s Muzzaffarnagar, Dharampal, was a great Gandhian scholar and wrote several books on Indian traditions, society, culture and polity.

At an incredibly young age, he was deeply influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s ideas. In the 1940s, he left his studies (BSc physics) halfway to join the Quit India Movement. He got involved in underground activities of the All-India Congress Committee (AICC) directorate. He worked with freedom fighters like Sucheta Kripalani, Girdhari Kripalani, Swami Anand and many more.

Just after India’s Independence, he participated in the programme for the rehabilitation of refugees from Pakistan along with Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Dr Ram Manohar Lohia, L C Jain and others. During this process, he discovered how communities can reorganise themselves when there is no interference from the state.

He was the co-founder of the Indian Cooperative Union (ICU). In November 1948, he left for Israel via Britain and while in Britain, he enrolled himself as an occasional student at the London School of Economics.

He married Phyllis Ellen, a British lady, and returned to India after visiting Israel. In the next few years, he travelled between India and England and was actively involved in various activities in association with Meerabehn and then with Jayaprakash Narayan.

During this period, he was elected general secretary of the Association of Voluntary Agencies for Rural Development (AVARD) with Jai Prakash Narayan as chairman. For the next two decades, Dharampal spent a lot of time studying the British records and other archival sources in an attempt to understand India and to further what Gandhi understood as the core of Indian society.

In1962, he first published, Panchayat Raj as the Basis of Indian Polity: An Exploration into the Proceedings of the Constituent Assembly. It presented extracts from the Constituent Assembly debates on the place of Panchayat Raj in the constitutional polity of independent India.

This debate ultimately led to the mention of Panchayat Raj in the non-enforceable Directive Principles in the Part IV of the Constitution. Through this work one can see how in the making of the Constitution of India, the individual is at the centre as opposed to the villages that Gandhiji was envisaging.

A large number of thinkers were unhappy about this development. Many have argued that this goes against the Indian notion of polity.

Civil Disobedience and Indian Tradition (1971) is the second of Dharampal’s books based on the materials collected in the course of his extensive study in the British archives. It presents documents of an intense civil disobedience struggle that raged in Benaras and several cities of Bihar for nearly two years – between 1810 and1811 against the imposition of a new house tax by the British administration. Indians found the tax to be new and hitherto unheard imposition, which went against the understanding of house amongst Indians, and therefore obnoxious.

The book anchored the Civil Disobedience of Mahatma Gandhi in an older and vibrant tradition. In this work, Dharampal could not only show that civil disobedience has a long history in Indian traditions, but also that Gandhi had an insight about the Indians and their ways of responding to a situation.

Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century (1971) compiles several articles by early British officers, scholars and observers about the Indian sciences of astronomy, mathematics and the Indian technological practices in metallurgy, agriculture, architecture and medicine etc.

The book created a new appreciation of the sophistication and efficacy of Indian sciences and technologies before the coming of the British. This work clearly shows what the nature of scientific traditions in India was and how advanced they were. It questions today’s notions about Indian traditions.

The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century (1983), his magnum opus, is again based on the materials collected from the British archives. It compiles documents of a survey of indigenous education ordered by Thomas Munro, Governor of Madras, in 1822.

The details of the indigenous schools and institutions of higher learning sent by the collectors of 21 districts of the extensive Madras Presidency, offers a fascinating picture of the extent, inclusiveness and sophistication of the then prevailing system of education in India. It also includes extracts from the reports of W Adam (1835-38) and G W Leitner (1882) about indigenous education in Bengal and Punjab, respectively.

This work debunks a myth that India was in darkness and a large number of people in India were denied access to education. This work shows that the public education at the elementary as well as higher levels was widespread in all parts of India until the British started uprooting it and replacing it with their education system.

This work shows that Indian system of education covered all sections of society and all castes. What is considered the low and Scheduled Castes today had a significant share in the system, both as students and as teachers.

Bharatiya Chitta, Manas and Kala (1993) is considered one of the most significant work of Dharampal. In this small, but seminal work, he reflects on the peculiarities of the Indian consciousness, the Indian sense of time and on the essence of being an Indian. The book thus lays down the broader perspective from which his corpus needs to be read.

Apart from these writings his major contributions include Understanding Gandhi, Rediscovering India, Despoliation and Defaming of India: The Early 19th Century British Crusade, The British Origin of Cow-Slaughter in India: with some British Documents on the Anti-Kine-Killing Movement1880-1894, The Madras Panchayat System: A General Assessment and so on.

Other than these works, he wrote extensively in Hindi as well as in English. There is a huge body of unpublished archives available in India with various institutions. Today, on the occasion of his birth centenary, once again, a series of books and other articles have come out of dust. The body of work collected and written by Dharampal is waiting for students and scholars to start engaging with it.

He was one of the very few great scholars who really took Mahatma Gandhi seriously. He was instrumental in setting up the Patriotic and People-Oriented Science and Technology (PPST) movement from Chennai which led to the exploration of Indian science and technology.

Multiple science exhibitions were organised in collaboration with other institutions through this initiative. Dharampal could bring people from different walks of life together for various innovative causes.

He delivered lectures and travelled extensively throughout India during the years 1982 to 2004. He was also actively involved in the 1975-77 anti-Emergency campaign, first from London and then from Patna. Some of the positions he took were uncomfortable to a lot of scholars, including his stance on Babri Masjid demolition as a new beginning in Indian politics.

Throughout his life he was a committed Gandhian who built scholarship to reflect on what India is and how Indian culture functions. He died in 2006 at Sevagram Ashram at the age of 84.

Unfortunately, our academic world and public discourse seem to have forgotten him today. In this background, Rashtrotthana Sahitya, Bengaluru has initiated publications of these texts by Dharampal under the title Dharampal Classic Series.

Soon we will have the Kannada translation of most of his works under Kuvempu Bhasha Bharati, Government of Karnataka.

On the occasion of his birth centenary, it is time for us to remember him and to bring him back to the centre of discussion. Remembering Dharampal is also remembering Gandhi. Remembering them is to remember and celebrate our culture.

Ashwini B Desai is Fellow, India Studies Unit, Centre for Educational & Social Studies (CESS) – Bengaluru.

Harshith Joseph is Fellow, India Studies Unit, Centre for Educational & Social Studies (CESS) – Bengaluru.