Sabarimala: From Justice Chandrachud To Media, No One’s Done Homework

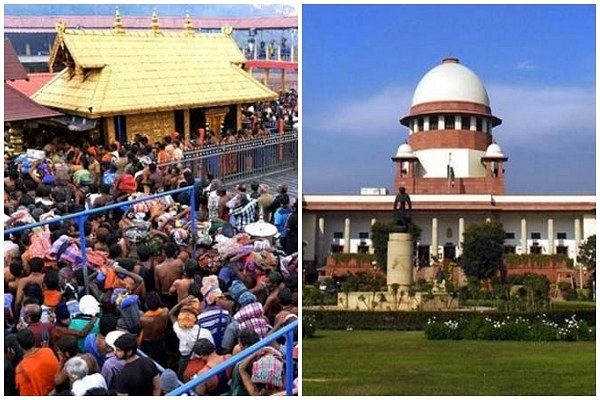

The Sabarimala ruling is nothing but trying to force-fit an Abrahamic binary approach into a more complex Indian reality.

The court’s negative attitude to Sabarimala needs questioning at many levels.

That the media does almost no homework before taking up its causes is obvious from the orchestrated tirade launched by several TV channels and newspapers over the resistance of devotees to accepting the Supreme Court verdict allowing all women to enter Sabarimala.

The temple, abode of Swami Ayyappa, has, thus far, banned women in the 10-50 reproductive age group from entering, and this has been touted as a huge assertion of patriarchal power to deny women their right of pray.

One can certainly understand modern women who dislike the entire idea of men deciding where they can go or where they cannot, but to paint the issue as something to do entirely with gender discrimination alone is misleading.

First, the discrimination – if it can be called that – is on the basis of age, not gender alone. This means some 40 per cent of Hindu women who are below 10 or above 50 are not discriminated against. If we assume that of the remaining 60 per cent who may be in the 10-50 group, half the women who are true devotees of Ayyappa voluntarily accept the restriction, close to 70 per cent of Kerala’s female Hindu population is not seeing this as discrimination. In the 2011 census, Kerala had a female Hindu population of 9.47 million; and 70 per cent of this number would add up to 6.63 million who may not see the Sabarimala restriction as burdensome. While it is true that Ayyappa’s devotees come from all over India, the proportions may not vary much for true devotees.

Second, the age-entry restriction applies only to Sabarimala, where Swami Ayyappa is worshipped as a naisthika brahmachari (eternal celibate). But there are 140 other Ayyappa temples in Kerala alone where these restrictions don’t apply. While Sabarimala obviously gets top billing for historical reasons, the point to underscore is that 140 other temples exist – not including those outside Kerala – for those who are true devotees, and would like to worship Swami Ayyappa when they are in the 10-50 age group. So, the discrimination is not general or widespread enough for the Supreme Court to treat this as unacceptable. The Right to Pray is guaranteed for anyone if they are willing to look beyond Sabarimala – and that, too, for a part of their lifetimes.

Third, Justice D Y Chandrachud, the judge with the sharpest critique of the Sabarimala ban, alleged that the burden of Ayyappa’s celibacy can’t be cast on women. This is a pathetic argument that sounds interesting at first sight, but will not bear close scrutiny. The world over, celibates do separate themselves from temptations of the flesh and the Catholic church is a prime example of this. So, does Justice Chandrachud believe that the burden of the Pope’s celibacy, and those of his cardinals, bishops and lesser priests, is being cast unfairly on nuns and Catholic women?

Most human beings, if they decide to abstain from anything, whether it is fatty foods or prime time TV, try and seal themselves off from temptations to maintain their resolves. Many Muslim restaurants, for example, shut shop when the faithful observe their Ramzan fasts. They open only when the fasts are to be broken after dusk. Surely, Justice Chandrachud is not naive enough to believe that the burden of someone’s fasting is falling on the non-fasters? It is faulty logic. Just because keeping women out is a part of the celibate make-up, it does not mean there is a corresponding burden on those kept out. They can go elsewhere. Justice Chandrachud went on to say that rights are for humans, not deities. Exactly. The celibacy logic of Sabarimala temples is for those devotees who abstain from sex and other kinds of indulgences when they come to this famous temple. It is not about the deity’s rights alone.

Just as Gandhari, when she realised that her husband was blind, blindfolded herself in order to be a partner in his disability, empathetic humans voluntarily accept limitations on their rights when the need arises. It is not unusual to find men and women taking sugar out of their lives when their partners suffer from diabetes, so that the restraint is shared. Justice Chandrachud’s observations are far from the humanity he talked about. One should applaud the People4Dharma and women who are #ReadyToWait to enter Sabarimala as empathetic humans, not disempowered lackeys of patriarchy.

Fourth, the Supreme Court judgement is based on a expanded reading of Article 15 of the Constitution, which prohibits “discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth”. But the problem is our Constitution is not a one-trick pony, with only one kind of rights. We have other fundamental rights, including the right to retain diversity in matters of faith, which article guarantees. To decide Sabarimala purely on the basis of Article 15 and not Article 26, which guarantees “every religious denomination or any section thereof” the “freedom to manage religious affairs, subject to public order, morality and health..” is a travesty.

Fifth, even assuming that Sabarimala is purely a male-bonding ritual – which it manifestly is not – one wonders why this should be so unacceptable in a post-feminist world, where groups of like-minded people band together to create their own special spaces for a while. It is perfectly all right for women to make special spaces for themselves for their own empowerment. Why would that be wrong for men, too?

The court’s negative attitude to Sabarimala needs questioning from many points of view. It is wrong to view the entry restrictions purely from a binary gender perspective which holds that if some women are barred for some time, it must be discrimination. It may not be any such thing.

This is nothing but trying to force-fit an Abrahamic binary approach into a more complex Indian reality.