The Breaking Of An Institution: How Government Control Is Harming Hindu Temples

Despite government control, temples have become sites of mismanagement, harassment, and commercialised rituals.

Ironically, temples survived for millennia without any control even as India went through rough weather under Islamic and British reign.

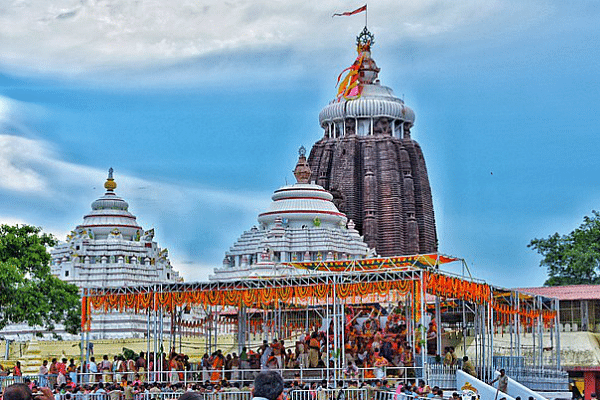

Last week, the famous Shri Jagannath Temple in Puri, Odisha, remained closed for devotees when the sevayats (servitors) refused to open the gates of the temple after a tussle with the police.

The past months had seen tensions escalating between the temple’s sevayats and the Odisha government following a Supreme Court order that imposes new ‘reforms’ on the temple.

The order came in response to a petition that raised concerns about harassment by the sevayats, inadequate hygiene, encroachments, commercialised rituals, and general “deficiencies in the management of the Shrine”.

Now the devotees are witness to yet another episode in a long series of legal disputes surrounding the Sri Jagannath Temple. Ever since the government passed legislation to take control of the temple in the early 1950s, conflicts have arisen again and again between the temple administration, the sevayats, the Gajapati or ruler of Puri, and the devotees.

Naturally, this case is part of a larger story. For decades now, state bureaucracies have intervened in the ‘management’ of Hindu temples, from controlling the finances to supervising the rituals. Along the way, politicians and judges have frequently condemned the mismanagement, which they claim is rampant in temples, and used these claims to justify the ongoing expansion of government control.

There is an irony here. It is precisely those temples that saw decades of government intrusion that are also the ones that have become hotbeds of conflict and mismanagement. To find remedies for the shortcomings in temples like the Jagannath Temple, the Supreme Court issued an order in June 2018, in which it directed the Union government and the Odisha government to create committees that should study “the management schemes” of major pilgrimage centres.

These included the Tirupati temple, the Vaishno Devi temple, and the privately owned temple of Dharmasthala in Karnataka. After first creating the space for a massive government take-over, the court now advised the government to look to other sites for lessons about proper management of temples, as though the problems can be solved by compiling a list of ‘best practices’.

The point is not that no well-managed ‘public’ temples (controlled by the government) exist or that all privately managed temples are beacons of harmony. Something more important is at stake. India’s larger temples are highly complex organisations. The tasks to be performed every day are numerous. Temple premises have to be cleaned, different kinds of water need to be drawn from specific wells, puja (ritual) is to be performed multiple times. These activities require a variety of flowers and other ingredients that need to be cultivated or acquired.

In addition, cooked food along with different kinds of prasad (food offering) needs to be prepared for rituals. The large numbers of visitors to the temple and their movements have to be monitored and handled. In some temples, food needs to be served to thousands of people and there are many other big and small tasks surrounding major festivals.

So, the work of the many people involved in the functioning of the temple needs to be well-coordinated and conflicts need to be proactively resolved or kept at bay.

Now, consider the following: the Indian temple is the most ancient type of organisation sustaining with this level of complexity. It goes back thousands of years. As a form of organisation, the temple survived in extremely hostile environments over millennia. They had to withstand Islamic invaders and rulers, who saw temples as sites of false religion and devil worship. British colonial governments viewed the temples in much the same way, but also exploited them as sources of revenue. The latest assault, of course, was the government take-over after Independence.

The temples also adapted to the fast-paced societal, technological, and demographic developments of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Hundreds of thousands of temples are thriving in today’s India and their numbers keep growing. Therefore, the Indian temple must be a highly resilient and adaptable organisation, at least as complex as a mid-sized company, to flourish under such challenging situations.

In post-Independence India, multiple state governments passed legislation that transformed ‘public’ Hindu temples into branches of state bureaucracy, which happen to deal in rituals and deities rather than, say, liquor licences or land records. In the case of the Puri temple and many others, this occurred with enthusiastic endorsement from the Supreme Court. Yet, for decades now, people have kept rediscovering that such temples have become sites of mismanagement, harassment, and commercialised rituals.

What else can be expected when pujaris are transformed by law into lower-level government servants? Predictably, they will also want their share of the revenue pie that India’s ‘public’ temples have become. The same is the case for politicians and bureaucrats sitting on the temple boards. Sadly, temples have begun to function as a means to pursue private interests.

This is precisely the kind of harm that government control of temples is unleashing. It is leading to the breakdown of the patterns of collaboration among the various groups of people involved in the temples, the very thing which allowed them to flourish for so many centuries. In this way, post-Independence India has perhaps become the most hostile environment ever faced by its temples. Leaving these institutions in the hands of state bureaucracies is a recipe for further decline.

Adding to government control of temples is the judicial intervention with regards to many traditions and rituals followed in temples. Why should people have to face these obstacles while they live in a country that claims to recognise the constitutional right to religious freedom? Should we not put an end to the unthinking political and judicial intervention that leads to disruptions in the functioning of temples and their traditions?

One of the tragedies of our times is our ignorance about the current state of affairs plaguing Hindu temples. It is time for social scientists to start figuring out how temples have worked in India, what kind of organisations they are, and what has gone wrong in the past seven decades.

We need to examine the legal grounds of the system of government control and build effective means for challenging this state of affairs in the courts. That is why a research project has been launched under the guidance of professor S N Balagangadhara, which aims to develop systematic analysis of these issues. This project will examine the legal and conceptual foundations of the state’s interference in temples, its historical origins in British colonial rule, the effects on the temples and their traditional practices, and the relation to the international legal tenets and jurisprudence about religious freedom.

To tackle the legal issues involved, it will re-examine state-level legislation about ‘Hindu religious and charitable endowments’ and the judgements of the Supreme Court and the high courts in cases related to temple management and temple entry, all from a jurisprudential point of view.

Finally, the enquiry will also focus on the Constitution of India and its articles concerning freedom of religion.

Dear reader, if you haven’t had the chance to do so yet, read the stories from our November 2018 issue “Leave Our Temples Alone”.

And for more, especially on freeing temples from government control, head back even earlier, to November 2017, for our “Free Our Temples” issue.