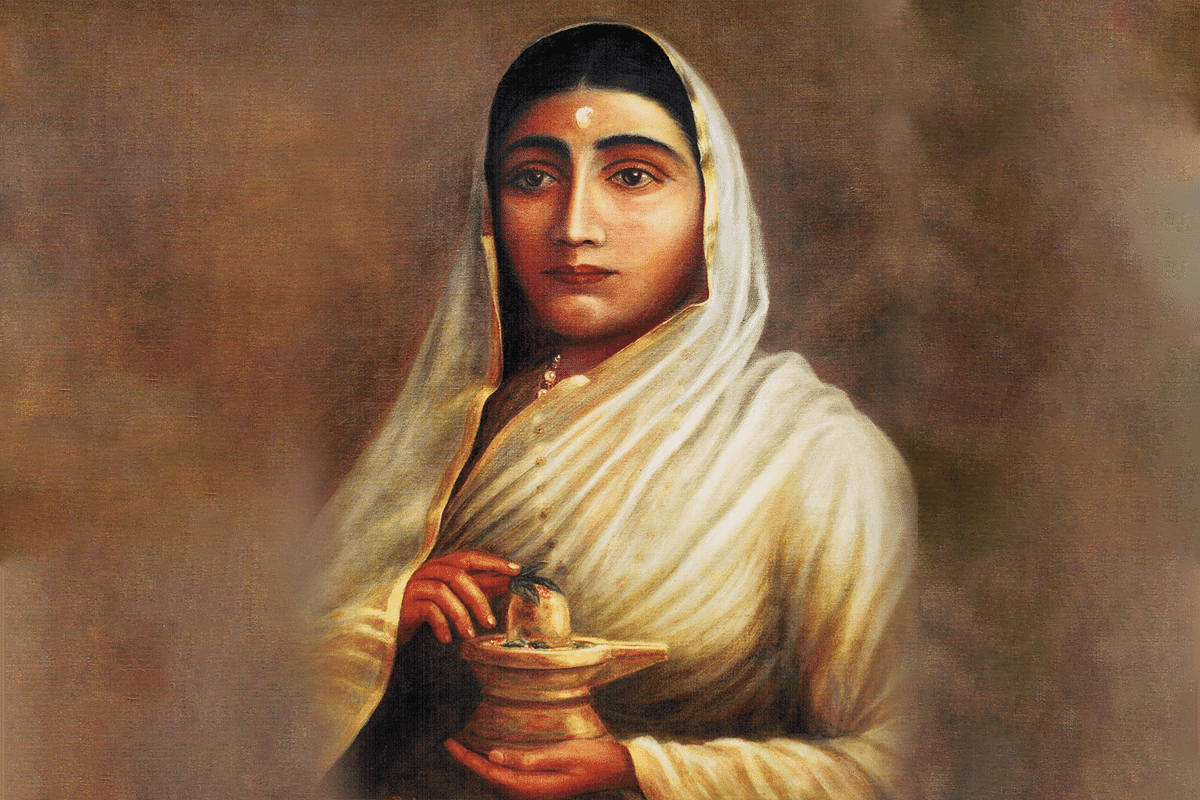

Why We Must Cherish The Legacy Of Devi Ahilyabai Holkar

Overcoming the 18th-century disadvantage of gender, Ahalyabai Devi stands out as a strong ruler spreading the message of dharma, rejuvenating Hinduism, and promoting the relatively modern virtues of small-scale industrialisation.

Devi Ahilyabai guided a fledgeling kingdom ably, rising far above the contemporary standards of administration and governance.

Hatshepsut is famous as the Egyptian queen who patronised arts. The Assyrian queen Sammuramat is known for fighting many wars, building a new capital and influencing lands far and wide. Isabella, the queen of Spain, is famous for bringing together an empire full of noblemen and streamlining the government machinery. These names, from times distant and lands far, get repeated in listicles and history throwbacks.

Devi Ahilyabai Holkar, who had most of these achievements to her repertoire and then some more, is a name largely unknown to most Indians, let alone to global history compilations. 13 August 2019 marks the 224th death anniversary of Ahilyabai. She ruled the province of Malwa for 28 years before she died, and created a strong local administration, overcoming the 18th-century disadvantage of gender. Taking over as the Queen of Malwa after all the male claimants to the throne had died, she stands out as a strong ruler spreading the message of dharma, rejuvenating Hinduism, and promoting the relatively modern virtues of small-scale industrialisation.

Ahilyabai was born in 1725 in a shepherd family in the district of Ahmednagar in Maharashtra. Belonging to the Dhangar community, she was among the few girls who learnt to read and write in that era. Malhar Rao Holkar, then the Holkar ruler of Indore, got her married at the age of eight to his son Khanderao, after a chance meeting. Khanderao lost his life in the 1754 battle in Rajasthan. The following events lead up to the legendary 1761 Battle of Panipat . Malhar Rao himself passed away in 1765 followed by the death of Khanderao’s son in 1767 who assumed the throne for a couple of years, with Ahilyabai as the regent. Ahilyabai then became the queen of Indore in 1767.

During this period, the Peshwa’s rule in Pune had significantly weakened in the aftermath of the loss at Panipat. Their regional satraps Holkars (Indore), Gaikwads (Baroda), Bhonsles (Nagpur) and Scindias (Gwalior) were all gaining prominence in their own right in their respective territories.

The biggest challenge Ahilyabai faced at the start of her reign was the constant plundering from the tribal population living in pockets to the west of her kingdom. She led the Holkar army in some of these battles against the intruders, establishing order in the kingdom. Ahilyabai set up her capital at the ancient city of Maheshwar on the banks of the Narmada River. The mighty fort that she built stands firm even today, overlooking a broad stretch of the Narmada. Although Holkars were based in Indore, she distinguished between her capital Maheshwar as the seat of power and Indore as the center for all economic activity. Under her rule, Indore prospered into a major trading hub from being a small town.

She brought about two important changes in the administration, both divergences from the traditions of her era.

Firstly, she vested the military power in Tukoji Holkar, a confidante of her father-in-law though not related. She took care of the administrative functions herself after assuming the throne.

Secondly, she separated the state’s revenue from the personal use of the ruling family. Her personal expenses were met from inherited wealth and the land holdings she had. The British regent John Malcolm has documented these administrative improvements in his memoirs Central India which were published, in 1880, long after his death.

Ahilyabai was politically astute as well. In 1772, she was said to have warned the Peshwa against allying with the British. At that time, the British were trying to take advantage of the vacuum in Pune, pitting claimants to the Peshwai one against the other. She also supported Mahadji Scindia in the power struggle in the northern part of Malwa which, for a whil, helped stabilise the region despite the problems in Pune. In the Uttar Vibhag of his eight-volume epic Marathi Riyasat, G.S. Sardesai has described how Nana Phadnis tried to pension off Ahilyabai on more than one occasion so that Tukoji could be the sole administrator in the Holkar region. But Ahilyabai refused to leave the public sphere despite all the prodding.

In his book Marathanche Itihasanchi Sadhanen, historian A.V Rajwade has traced the failures of the Marathas (with Peshwas in the lead) in northern India, then referred to as Hindustan, to “their failure to work out Maharasthra Dharma in a wider perspective”. Rajwade postulates that if Marathas had emulated Ahilyabai and succeeded in evolving a sound and just administration in their northern conquests, the people of Hindustan may have gladly accepted their rule.

In the times when most of the kingdoms in the then Bharatvarsha were reliant on trade and agriculture, she promoted weaving and textiles in Maheshwar. Burhanpur, a prominent town during the Mughal era, had a tradition of handloom industry. The town, not very far from Maheshwar, had been in a terminal decline after the Mughal influenced waned. Ahilyabai relocated some of these weavers to Maheshwar and started a local industry. The Maheshwari saris, sold even now, are known for their patterns which mimic the power and the vistas of river Narmada.

The most significant contribution of Ahilyabai, however, comes in the preservation, reconstruction and refurbishment of a host of Hindu sites which she carried out during her 30-year rule. From Gangotri to Rameshwaram, and from Dwarka to Gaya, she spent money on rebuilding temples destroyed under the Mughal rule, in restoring the past glory of holy sites, in building new temples and in building ghats for easy access to almost all major rivers in the Bharatvarsha.

The list of the temple architectural interventions by Ahilyabai is endless. The most significant one, however, is the current Kashi Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi. Destroyed by the Mughal ruler Aurangzeb to build the Gyaanvapi mosque, the temple was restored in its current form by Ahilyabai in the year 1780, 111 years after its destruction. Ahilyabai also refurbished the Dashashwamedh Ghat, site of the famous Ganga Aarti, built originally by Nanasaheb Peshwa and the Manikarnika Ghat, the main cremation site in Varanasi.

The Somnath temple, witness to the regular destruction by a host of aggressors over the centuries, was restored in 1783 by all the Maratha confederates, with significant contribution from Ahilyabai. She contributed to the betterment of facilities at Dwarka as well. At Bhimashankar and Trimbakeshwar, Ahilyabai constructed bridges and rest areas. With temples and rest areas in Kedarnath, Srisailam, Omkareshwar and Ujjain, Ahilyabai contributed to the improvement of facilities at other holy sites hosting Jyotirlingas too.

Among the imposing temple structures, constructed by Ahilyabai, which survive today is the Vishnupad Temple in Gaya. Legend has it that this is the site of Lord Vishnu crushing the demon Gayasura, and his footprint is etched in rocks. The temple is built on these rocks bearing 40 cm long footprint of Lord Vishnu. Ahilyabai, despite being a devout Lord Shiva devotee, got this temple constructed in 1787. The Ramachandra temple in Puri, Hanuman temple in Rameshwaram, Shri Vaidyanath temple in Parli Vaijnath and the Sharayu Ghat in Ayodhya all bear her contributions.

It is fair to say that no other individual in the modern era has worked towards the renovation and overhauling of Hindu holy sites as Ahilyabai. If, in the current day, Hindus can visit and appreciate the centres so integral to the ancient history and evolution of the dharma, a significant part of the credit goes to her. It is unfortunate that most of these places do not bear inscriptions in her name, but it was perhaps her operative style too— the architectural restoration work was carried out of an innate sense of religiosity, and was not linked to politics or gaudy display of wealth.

Ahilyabai died in the year 1795 at the age of 70. Her legacy is not enshrined in her name despite the works she undertook all over India. But, more worryingly, her legacy is not documented in a structured way in history textbooks or popular references either. Part of the problem is the general absence of any non-Mughal, non-British narratives in contemporary Indian history books. But Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra not doing their bit in celebrating this gutsy queen is the bigger issue. At least at the local level, there should be attempts to correct broad New Delhi driven historical exclusions.

Joanna Baillie, a Scottish poet and dramatist, said this of Ahilyabai in 1849 (published 1904):

“For thirty years her reign of peace,

The land in blessing did increase;

And she was blessed by every tongue,

By stern and gentle, old and young.

Yea, even the children at their mother’s feet

Are taught such homely rhyming to repeat

“In latter days from Brahma came,

To rule our land, a noble Dame,

Kind was her heart, and bright her fame,

And Ahlya was her honoured name.”

The honorific Devi, appended to Ahilyabai Holkar, is the mark of genuine love, affection, and respect the people of Malwa and Nimad have for her. Born a shepherd, Devi Ahilyabai guided a fledgeling kingdom ably, rising far above the contemporary standards of administration and governance.

(This article was earlier published here on 13 August 2016)