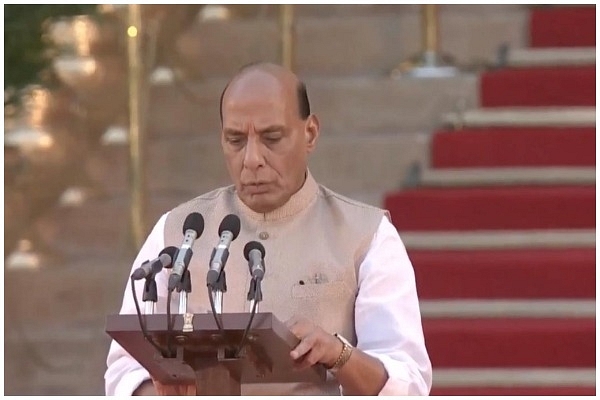

Five Key Challenges Before India’s New Defence Minister Rajnath Singh

Modi’s image of a leader who is incorruptible and tough on national security gives Rajnath Singh a unique opportunity to push military reforms and modernisation of the forces without any adverse political fallout.

Over the past five years, the Defence Ministry had three different ministers, none serving long enough to push through military reforms or eliminate the bottlenecks in the procurement system. Some critical acquisitions, such as the purchase of the Rafale fighters and howitzers, were undertaken, but many continue to hang fire. Key policy changes, including new procurement guidelines and the Strategic Partnership Model, were introduced, but had made little headway by the time India went to polls.

Therefore, India’s new defence minister, Rajnath Singh, will face multiple challenges as he takes over the mantle of building up the capabilities of the three armed forces, among other things. Here are the five most critical ones:

1) Fixing Budget Allocation

In 2011-12, the MoD spent around Rs 35,570 crore, or 17.6 per cent of its total budget on pensions. This has ballooned to Rs 1,12,079 crore in 2019-20, an increase of nearly 200 per cent, and accounts for 26 per cent of the total budget. Apart from pensions, the allocation for pay and allowance, which is part of the MoD’s Defence Services Estimates, also claims a large part of the defence budget. At Rs 1,24,821 crore, the allocation for pay and allowance forms close to 30 per cent of the total defence budget for 2019-20, growing from 13.2 per cent in the 2011-12. Put together, the allocation for pension and pay and allowance form 55 per cent of the MoD’s total budget of Rs 4.3 lakh crore. In the 2011-12 budget, the allocation for pensions and pay and allowance claimed 43.5 per cent of the total budget.

However, the share of capital allocation, which is meant for the procurement of new equipment (that is, modernisation), has come down to 24 per cent in 2019-20 from 32.5 per cent in 2011-12 despite an increase in capital allocation from nearly Rs 68,000 crore to around Rs 1.08 lakh crore during this period.

Therefore, over the years, the share of capital allocation in the defence budget has decreased while that of pensions and pay and allowance has grown substantially. This is because the government can’t deny pension to the 30 lakh retired security personnel and civilian employees and salary and allowance to millions more who are currently serving, while it can delay, without immediate consequences, the procurement of new equipment, depending upon the availability of funds. But given the threats India faces, this trend is not sustainable. The defence minister will have to come up with a solution to this problem, and soon.

2) Pushing Military Reforms

Over the last three decades, India has failed to push through any significant reform to make its manpower-intensive military into a leaner and meaner force, while China has been able to accomplish much. The lack of reforms has made sure that the Indian military’s ability to fight swift wars remains constrained.

As attrition wars have become more and more unlikely, the People’s Liberation Army has cut its size in favour of a more agile air force and a true blue-water navy, most recently in 2015 with a reduction of 3 lakh. Army Chief General Bipin Rawat did appear to have taken a clue, constituting three committees in 2018 to look into manpower rationalisation, paring down army headquarters and examining the officer cadre, but the process does not appear to have moved significantly since, except orders to move 229 officers from the Army headquarters to border areas.

But manpower rationalisation is not the only reform that has to be pushed through. A more controversial reform is the creation of theater commands to promote jointness among the three services for better utilisation of limited resources. The three services, especially the Air Force, have different opinions on this issue, but appear to have agreed on the option of having a Permanent Chairman of Chiefs of Staff Committee, a post envisaged as a single-point military adviser to the government. While this can be an intermediate stage, Singh will have to work towards building consensus among the three services to get to the stage where theater commands are acceptable to all, or develop a new mode of jointness that works for India. The sooner India moves away from coordinated to integrated operations, the better.

Modi’s image of a leader who is tough and uncompromising on issues related to national security gives the defence minister a unique opportunity to put these reforms into motion without any adverse political fallout.

3) Fixing Procurement

Despite some efforts between 2014 and 2019, India’s defence procurement remains over-bureaucratised and, as a result, slow. Delays in decision-making, combined with the risk averseness of the bureaucracy, has had a debilitating effect of the war fighting abilities of the forces. The Prime Minister himself accepted this too, when he said the result of the India-Pakistan dogfight in skies over Kashmir would have been different if the Indian Air Force had Rafale fighters. The first Rafale fighters will arrive in India in September this year. The process began in the late 2000s.

The unprecedented politicisation of defence procurement by Rahul Gandhi’s Congress is only likely to nudge the bureaucrats to be even more risk averse.

The lack of experience and professional training of those part of the acquisition cycle in complex legal, contractual and technical matters, as the Comptroller and Auditor General of India too has identified, adds to the delays caused by the bureaucratic bottlenecks. “A specialised cadre pool of Acquisition Managers should be developed by imparting suitable training in different areas of acquisition viz. Project management, contract negotiations, contract management; and exposure to professional best practices of procurement,” the CAG had suggested over a decade back. Not much appears to have been done by successive governments in this regard.

Also, the decision to set up a dedicated Defence Procurement Organisation to institutionalise professional expertise is yet to materialise. The Dhirendra Singh Committee had articulated the need of such an agency in 2015.

These issues will need the defence minister’s immediate attention. And even as he fixes these problems, Singh will have to work through the existing set up to buy some critical equipment—namely fighter jets for the air force to add to the Rafale numbers, and submarines and helicopters for the navy—on an emergency basis.

Other critical acquisitions programmes that Singh will have to steer: induction of Tejas fighter in numbers to replace MiG-21s, Airborne Early Warning aircraft, tracked, truck-mounted and towed artillery guns and minesweeper.

4) Increasing Private Sector Participation

The participation of India’s private sector in defence manufacturing has improved over the last few years. Success stories include the ballistic helmets built in Uttar Pradesh’s Fatehpur by Indian firm MKU, bulletproof jackets made by SSMP Private Limited and the involvement of private players Mahindra and L&T in critical purchases such as the M777 Ultra Light Howitzers and Vajra K9 self-propelled tracked, respectively.

The Defence Procurement Policy of 2016 was a step forward towards increasing the private sector’s participation, but challenges persist. For example, private players signing a contract are required to deposit a bank guarantee. In some cases, this amount to a large part of the total order value, affecting the availability of liquid funds with the vendor. This, in turn, affects the vendor’s ability to deliver timely.

Moreover, most contracts in India take three to five years to materialise. Therefore, until a vendor has other sources of income or funding to sustain, it is even difficult to survive in the market. While this is not an issue for large businesses like Mahindra and L&T, start ups and small and medium enterprises are affected by this.

The difference in cost of capital for private players and state-owned, as pointed out by KPMG and Assocham in a report on Make In India, makes the former uncompetitive. The cost of capital for private players is around 10-12 per cent per year. For the state-owned defence firms, the capital requirement is funded by the Ministry of Defence. Therefore, if a contract takes two to three years to materialise, “the costs for a private player end up being 25-30 per cent higher than the costs for public entities”.

The monopoly enjoyed by government-owned defence firms on everything from boots to battle tanks also shrinks the space for the involvement of the private sector.In many cases, the government-owned firms get contracts on nomination basis.

The Strategic Partnership (SP) Model aimed at increasing the private sector’s share in defence manufacturing also appears to have made little headway. For example, Project 75-I for six conventional submarines, which is to be executed under the SP model, is yet to take off. The process of acquisition of 111 naval utility helicopters to replace the obsolete Alouette II/Chetak is also moving slow.

Hence, Singh has a lot of critical issues to sort with regards to the participation of Indian private players in defence manufacturing.

5) National Security Strategy

A comprehensive national security strategy, which spells out the challenges that India faces in this realm and the tools needed to neutralise them, can prove to be an effective guide for building capabilities of the armed forces. An effective national security strategy would identify the military resources required to deal with the challenges that it outlines. In the absence of a strategy, India’s response to challenges, including the procurement of equipment for the armed forces and development of technology for the future, has remained ad hoc.

As defence minister, Singh will have to make sure that the Defence Planning Committee (DPC) established in 2018 under the national security adviser Ajit Doval and tasked with drafting India’s national security strategy, delivers. Attempts at preparing a national security strategy have failed in the past. Also, the longer the DPC takes to prepare a security strategy, the lesser time he will have to use it to put into motion the acquisition of capabilities required in the future.

Singh has both, political heft and Modi’s mandate to push through these reforms and purchase. He also has an opportunity to leave a lasting legacy, something he could not do as Home Minister. He should not let it lapse.