Five Things You Should Know About Galwan Valley, The Place Where Indian And Chinese Troops Clashed

Indian and Chinese armies have been locked in a tense stand-off at three points along the Line of Actual Control — the Galwan River Valley, Hot Springs area and the Pangong Lake — since early May.

The clashes on Monday night (15 June) took place in the Galwan Valley.

On the night of 15 June, Indian and Chinese troops clashed with each other using stones, sticks and clubs in eastern Ladakh, resulting in casualties on both sides.

In a brief statement on this development, the Indian Army said that the incident took place when the process of ‘disengagement’ was on in the area.

Indian and Chinese armies have been locked in a tense stand-off at three points along the Line of Actual Control — the Galwan River Valley, Hot Springs area and the Pangong Lake — since early May.

Earlier this month, news reports said that the two sides have begun disengaging at two of these points.

The clashes on Monday night took place in the Galwan Valley, the northern most of the three points of stand-off.

Here are five things you should know about this place:

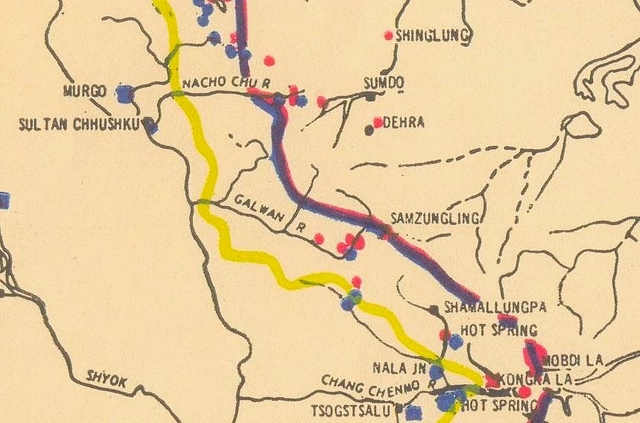

1) The Galwan Valley is located in north-eastern Ladakh, west of China-occupied Aksai Chin. The map below gives an idea of the location of the Galwan Valley in relation to other places in Ladakh, such as Leh and Kargil.

The red pointer in the map shows the approximate location of the confluence of the Galwan River (flowing westwards from Aksai Chin), named after Ladakhi explorer Ghulam Rasool Galwan, with the Shyok River, a tributary of the Indus.

2) The 255-kilometre long Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldi Road runs through this area. The road, for the most part, runs parallel to the Shyok River.

Critical for connectivity in north-eastern Ladakh — termed Sub-Sector North by the Army, the D-S-DBO road provides all-weather access to far-flung areas abutting the 38,000 square km territory of Aksai Chin under Chinese occupation, such as the Depsang Plains, which saw a tense India-China stand-off in 2013.

The road had been under construction for over a decade. The project was monitored directly by the Prime Minister’s Office.

In 2011, by the time a large part of the road was complete, an inquiry into its construction found the road had been laid on flat terrain along the bed of the Shyok River instead of being built on the mountain side.

As a result, every year during summer, as melting snow flooded the Shyok river, some portions of the road were damaged.

A large part of the road, around three quarters, was realigned by the Border Roads Organisation, along with the construction of India's highest altitude all-weather permanent bridge in eastern Ladakh, and completed in early 2019.

The Chinese, some reports say, were upset with the construction of this road and ‘intruded’ into the Indian side in the Galwan Valley to dominate the road.

3) A feeder road and a bridge that India is constructing to Patrol Point 14 in the narrow Galwan Valley from the D-S-DBO road was the immediate cause of the stand-off in this part of Ladakh, some reports have claimed.

India has refused to stop the construction of the bridge.

“The work on the bridge, which is about 7 to 7.5 kilometres from the LAC, had started much earlier. However, around 10 May, the Chinese objected to it. However, the work on the bridge continues. The ongoing issues have only made us work faster on this bridge,” ThePrint quoted a source as saying.

Over the last one week, the BRO has been moving labour to border regions, including Ladakh, to work on its infrastructure projects. Experts see this a signal to China on India’s infrastructure development along the LAC.

4) Indian and Chinese troops clashed here in 1962.

In July 1962, as tensions with China started to rise, India decided to set up a new post in the Galwan Valley to block a possible approach to Leh via Shyok Valley.

The Western Command considered this an unnecessary provocation and was against the move, but the decision of the Army Headquarters prevailed.

As a result, a platoon-size post was established in the region between 4 and 6 July by the First Battalion of the 8th Gorkha Rifles.

Just days later, on 10 July, around a hundred PLA troops encircled the post and took positions within 50 yards of it but did not attack.

In a note on 12 July, India told China that its forces in Galwan were “not only poised in menacing proximity to existing Indian posts in the area” but that “their incessant provocative activities may create a clash at any moment.”

Although tensions subsided a little, the post remained surrounded by the Chinese for the next few months and had to be maintained by air.

When the Chinese finally attacked on 20 October, the post had been reinforced by “a company less a platoon” of the 5th Battalion of the Jat Regiment.

As a result, the strength on the Indian side came up to “two officers, three JCOs and 63 other ranks”.

The Chinese Army overran the post in hours, killing “the Regiment Medial Officer, two JCOs and 30 other ranks”.

Major (later Lieutenant Colonel) Shrikant Hasabnis, a company commander in 5 Jat, and others were taken Prisoners of War.

“When we were flown into that post we knew we were walking into a death trap. But the 60 had no meaning because more than 2,000 Chinese were around us in circled conditions and not only that, they had a very big ring around us of trenchers, morchas, and communication weapons. They used to show their weapons as if you show windows,” Lt. Col. Hasabnis recalled a few years ago.

“...jawaans used to say, ‘saab yeh to haath baandh ke bhi ayenge to hum inko kahi nahi le jaa sakte (Even if they come with their hands tied, we can’t take them anywhere)'. Even our jawaans were making a joke out of it,” he said in 2012.

5) India and China are holding talks at the military level to diffuse the stand-off in the Galwan Valley and other areas in eastern Ladakh.

At least one report says that the Chinese have refused to discuss its ‘intrusion’ in the Galwan Valley, “instead claiming ownership over the entire area”.