A Budget With A Vision And A Heart

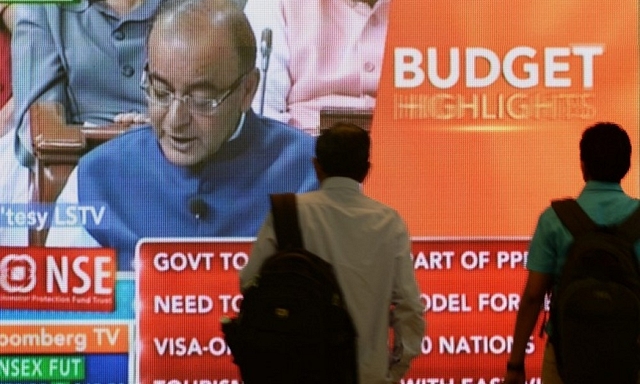

So, was it a Big Bang Budget? Well, no, but then, Arun Jaitley is a lawyer, and lawyers are conservative by nature. Lawyers don’t believe in Big Bangs.

However, it was certainly a strong statement of intent, a clear indication of the government’s broad economic philosophy, a roadmap for the future. The Modi government is committed to a market economy, without vacating the spaces that the State must occupy. It is serious about poverty alleviation, about inclusion, about powering up our struggling agricultural sector, Make in India, about ease of doing business, about encouraging entrepreneurship.

The true impact will be felt only a few years from now. But it is fair to say that Reforms 2.0 has begun, reforms with both a head and a heart.

If India finally has a social security net, which Jaitley has promised to weave, it will have a transformative effect on our economy and society. Just consider one of the less obvious side-effects. Industry and liberal economists have been crying themselves hoarse for two decades about the need to change labour laws. Yes, those changes—whatever the leftists tell you—will benefit not only businessmen but also labour. But politically, it is extremely difficult—if not impossible—to push through these changes without a social security net in place.

If India finally has a Bankruptcy Code (Jaitley has used the adjective “modern” to describe it), it is a huge boost for the market economy. One can never have a true market economy without allowing failure and exit. The BIFR has failed us completely on that. We need something entirely new and pragmatic.

If the government does push through legislation to dramatically reduce the multiple permissions needed today to start a new business, it will certainly reduce the costs of enterprise significantly. Currently, the process to set up a limited-liability company is so daunting that only the bravest of hearts survive it.

If Jaitley does follow through with policies that encourage the use of credit and debit cards with the final long-term goal of having a cashless economy, the efficiencies unleashed will be enormous.

If these, and some other things promised in the Budget, happen, India will rock.

One is using so many “if”s, because almost all of these outcomes are dependent on implementation and determined and focused execution. Our bureaucracy and administrative structures are ossified. They require a massive push to rid themselves of lethargy and get moving, to realize that what is good for the country is also good for them, not the other way round.

The elephant in the Indian economy’s room has always been infrastructure. Countless committees have deliberated on various infrastructure sectors over decades and filed many reports—and most of them very sensible ones. But other than in the roads sector, have we really seen anything changing? Our ports are an embarrassment, our power situation is shocking for a country that believes it is a major economy, our urban transport systems are a mess.

Funding infrastructure projects has of course always been the core issue. This Budget has tackled it brilliantly. The government is going to pump Rs 70,000 crore into the sector, and while announcing this, Jaitley said: “But that is not enough.” In 25 years of watching Budget speeches on television, I have never heard a Finance Minister say this, that something is not enough. Jaitley deserves a lot of respect for just that line he uttered.

His solution to the “enough” problem has been to set up a Rs 20,000-crore infrastructure fund and issue infrastructure bonds. Now, at a minimum leverage ratio of 6:1, that fund will be able to raise Rs 120,000 crore. That’s a lot of money, but just the sort of money we need to fix our roads, power, water. The tax-free bonds will certainly be popular, so that could give the government many more thousands of crores.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) are absolutely essential for infrastructure projects of many types, but they have not been very successful in India because of disagreements on risk-sharing. Jaitley made it clear in his Budget speech that the government understands the problem and will take on the lion’s share of the risk. This is practical and progressive. He has also spoken about corporatizing our major ports—a solution that has been staring us in the face for years, but no one has done anything about it.

Getting rid of the wealth tax too is absolutely practical. If our annual wealth tax collection, in a $2 trillion economy, is Rs 1,000 crore, it is obviously an unimplementable, and hence, useless, tax. The government is almost certainly spending more than Rs 1,000 crore to collect that sum. Jaitley has replaced it with a 2% tax surcharge on the super-rich, which they can well afford. And that, according to his calculations, will get the government Rs 9,000 crore, at no extra cost—in fact, less cost.

The promise to lower corporate tax from 30% to 25% over the next four years must have surprised India Inc, because it did not ask for any such thing. But the logic is impeccable. Effective tax collection is actually 23%, given the various exemptions, incentives and concessions. The actual figure would be lower if one takes into account the cost of endless and innumerable litigations. So, do away with the exemptions, settle for a flat lower rate. And do it gradually, without springing a surprise on all parties concerned. It is also a message to the world that India is aligning its tax rates with developed world percentages.

As for GST, work on which has been progressing slower than our timetable-less goods trains, we now have a firm deadline: April 1, 2016. It will not be easy to meet that target, but the government should simply go forward with it, even if Mamata Banerjee and some other chief ministers do not see reason. Let GST prevail in all the other states, and the recalcitrant ones will perforce have to fall in line, sooner or later. This was the way VAT was implemented; the same should be done for GST.

As for Make in India, the Budget addresses it smartly, through facilitating moves rather than tax sops, which only work up to a point, and that too in the short run. Infrastructure investment, ease of doing business, encouraging start-ups, lumping foreign portfolio investment with foreign direct investment in company shareholding—all of these will aid the manufacturing sector, and create jobs.

Overall, this is a visionary Budget, with a long-term view, very different from some cynical short-term-focused ones we have seen in recent years. For instance, there has been no waiving off of farmers’ loans. Instead, a microfinance-refinance institution has been proposed. Large sums of money have been set aside for irrigation projects. Tax breaks have been given to build a cold storage chain that the agriculture sector very badly needs.

What are the negatives? Well, the Budget could certainly have been clearer on the issue of disinvestment and privatization. One is still unsure about what Mr Modi and Mr Jaitley really think about this. And the other completely inexplicable thing—why has Jaitley not abolished retrospective taxation? He should have done it in his last Budget, and provided the weak excuse that the matter is sub judice. He cannot provide the same excuse this time because the government has already said that it will not contest the Vodafone case. So why shy away from making a clear policy statement on something that is patently unfair and is a little thorn that has a disproportionate impact on foreign investor confidence in India? This is strange, and one cannot understand what the big hesitation is all about.

To end, this Budget has a lot for the poor and the not-well-off of our country. All Indian Union Budgets do. But this Budget seems to be doing it smarter and more effectively. To incentivize life and health insurance (in addition to offering very cheap schemes for the underprivileged) and pensions is intelligent liberal economics. But, also, and this many may not consider so important, the many proposals to make lives easier for senior citizens and the disabled. No other Budget that I recall paid so much attention to these neglected sections of our society.

We as a culture pride ourselves on venerating our elders. The reality is very different. And we as a society and economy do hardly anything for the disabled. When we use that routine word “disadvantaged” in our discourse, it usually means only the poor. But the poor are hardly the only people we as a nation and people need to take care of.

This Budget tries to correct that. This is a Budget with a vision and a heart.