Ambani Vs Bezos Vs Walmart: Finally, A Local Goliath Takes On Global Godzillas

In a high-stakes game where big investments have to precede big customer gains, India has no option but to back the likes of Ambani against Bezos.

If India is to avoid tech colonisation, the prime precondition for success is the creation of a local 800-pound gorilla – or a couple of them – to take on global Godzillas such as Amazon and Google. This is what China did, by tilting the field in favour of Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu and against the global biggies. This is what India too will have to do, sensibly and intelligently, without making it about protectionism.

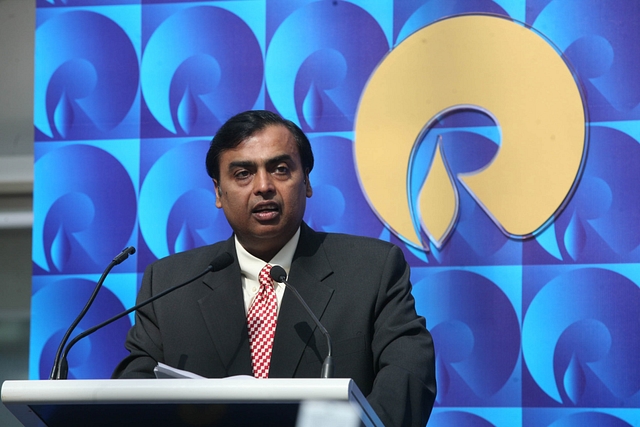

The last few months have seen the emergence of one such possibility: Reliance Industries, headed by billionaire Mukesh Ambani. If anybody can take on the challenge of Amazon and Google at least locally, it is Ambani. But he will find it tough to do it alone. Despite having the resources to invest big in e-commerce and payments systems, the resources of his global rivals are even bigger. Moreover, Ambani is already stretched, having bet the farm on Jio by investing more than Rs 2,00,000 crore on the data network. Hence, a favourable regulatory regime matters. Mukesh Ambani is no slouch when it comes to taking the battle to the regulatory forum.

Last week, when Ambani talked about his new online shopping platform that will connect 1.2 million Gujarati retailers and shopkeepers using connectivity provided by his Jio network, it was an early indication that he does not intend to give the global giants a walkover. The idea is to connect local kirana and mini departmental stores to the Ambani e-commerce platform, by offering them customised billing, tax and inventory management systems at low cost.

In political terms, it is about Ambani helping the local Davids take on the global Goliaths, though he benefits in the process. But even in terms of business logic, it makes sense, as the new buzzword is omnichannel selling and marketing – and not just online versus offline. Retailers have to use any platform, offline or online, to sell to customers, and Ambani is combining the two in this move. Walmart, an offline powerhouse, bought India’s biggest online player Flipkart and Amazon bought the More retail chain from the Birlas last year as part of this same omnichannel trend.

At the Vibrant Gujarat summit last week, Ambani made a strong pitch for data localisation. He said: “In this new world, data is the new oil. And data is the new wealth. India's data must be controlled and owned by Indian people and not by corporates, especially global corporations. For India to succeed in this data-driven revolution, we will have to migrate the control and ownership of Indian data back to India in other words, Indian wealth back to every Indian.”

The Reserve Bank of India has already mandated that all payments service providers must migrate their Indian customer data to India-based servers, and the Mastercards and American Expresses of the world are fighting back hard.

Ambani opened another front in the regulatory battle when Reliance Jio called for more regulation of OTT (over-the-top) platforms like Hotstar and Amazon Prime which use the telecom network to deliver entertainment over broadband, but additionally provide their own interaction capabilities for customers through apps. Jio has said that OTT platforms need to be regulated and monitored in order to allow for lawful interception of messages and prevent criminal, anti-national and anti-social behaviour.

This demand for greater regulation of the OTT players, which is backed by Paytm and Sharechat, among others, has put several backs up, including those of Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Google.

Last month, in a surprise move, the government tightened the rules for e-commerce marketplaces, preventing them from using related firms to inventory and sell products on their platforms. A note from the Commerce and Industry Ministry in December said: “An entity having equity participation by e-commerce marketplace entity or its group companies, or having control on its inventory by e-commerce marketplace entity or its group companies, will not be permitted to sell its products on the platform run by such marketplace entity.” This means Amazon, which holds a stake in Cloudtail, cannot sell products sourced and inventoried by the latter from 1 February.

Whether these regulatory moves are directly influenced by domestic players or have been taken autonomously, they will certainly slow down players like Amazon and Flipkart, where Walmart is the controlling player.

This will give time to Ambani to ramp up his own omnichannel operations, which include over 10,000 physical retail stores of Reliance Retail.

Ambani already is the country’s biggest wireless broadband player, focused as the Jio service is on data rather than voice. With voice revenues for the incumbents crashing, Jio bids fair to reach the No 2 position in terms of subscriber base fairly soon. It is only 50-60 million users below Airtel. In November 2018, Jio had 271 million users to Airtel’s 341 million. Jio’s numbers have since risen to over 280 million. In the attrition game, where growth will depend on getting subscribers to shift from their existing providers to Jio, both Airtel and Vodafone Idea are losing out to Jio’s low tariffs. The former two will bleed, while the latter continues to grow users by keeping tariffs low.

The Ambani e-commerce play, though late in the day, pits him directly against Jeff Bezos of Amazon and Walmart, who have committed billions of dollars of investment to grow their marketplace platforms in India.

If Ambani is to hold his own and even eat into their lunches, he will not only have to invest big again – Jio all over – but also integrate his broadband network, his 10,000-store retail chain, his payments bank, and his media and entertainment businesses into one solid business platform.

Some regulatory help will improve his chances. In a high-stakes game where big investments have to precede big customer gains, India has no option but to back the likes of Ambani against Bezos.