DeMo Impact: Why Jaitley Should Wait For December Data Before Saying “All Is Well”

It is not easy to ask politicians to decline credit for numbers when they look good, but in the case of demonetisation, waiting a bit before claiming “no adverse impact” would be more fruitful.

The November post-DeMo numbers are cause for one cheer, not two or three. Judgment for that will have to wait.

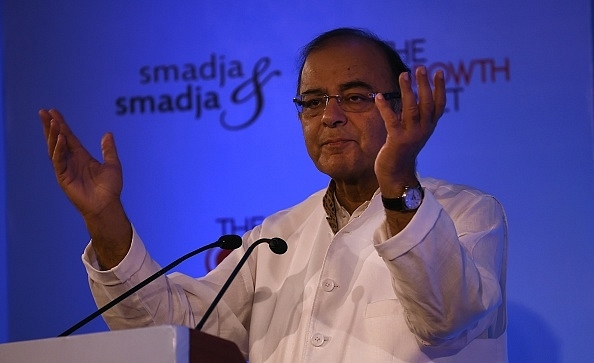

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley was quick off the mark to claim that demonetisation (DeMo) did little damage in November, armed with figures for direct tax receipts (up 13.6 per cent, net of refunds) and indirect taxes (up 26.2 per cent). He also pointed to areas of growth, including life insurance, mutual funds, aviation and petroleum – sectors in which demonetised notes were usable for much of November. Also, rabi sowing was 6.3 per cent higher than last year, even though it happened during the DeMo cash crisis in rural areas.

He did not deny areas of concern, but is quoted by The Hindu as saying: “Of course, there would be areas which would be adversely impacted, but what was predicted by the critics has to have a rationale with the revenue collection. Assessment can be unreal but revenue is real.”

He is right, of course, but he would be unwise to take too much solace from this. Nor should he dismiss the impact of demonetisation as marginal till we get more data over a longer period. The tax figures up to 19 December, which is what he shared, may not be indicative of revenue trends for the rest of 2016-17. December and January performance would be more indicative, for many sectors respond to demand compression with a lag. Also, the first order impact on the organised sector may have been less than the second order impact, with some degree of distress being reported from small businesses, the informal sector and rural areas.

Consider just two examples: in November, Maruti, Toyota and Renault reported a jump in sales, but a lot of this could be due to the waiting period for some cars. People who bought in November may have booked in earlier, especially in models like Suzuki’s Brezza, which had a waiting period. Ditto for the tyre industry, which reported robust sales in November, but December figures could be more revealing.

There could also be another reason for the optimistic tax data. If we assume that many black money holders chose to deposit their old Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes in their bank accounts (or other related accounts), this fact itself would have forced them to pay higher taxes, even though their actual sales figures may be lower. Tax figures in a period of demonetisation panic may not reflect the natural growth of actual sales revenues.

Even GDP data for the October-December quarter, due only in February, but which we may get earlier this time (the CSO has agreed to give advance estimates of GDP by mid-January since the budget is on 1 February), may be off the mark. Reason: the third quarter is when agricultural growth is expected to have been good due to the good kharif harvest. So even if GDP remains around 7 per cent (give or take 0.2 per cent either way), it may reflect agricultural growth. Only the sectoral figures for manufacturing, trade, etc, may give a holistic figure. It is these numbers that will tell a tale on DeMo impact.

In any event, the second order effects may continue well into the fourth quarter, as people adjust to the reality of lower cash till at least January-end or even February.

It is not easy to ask politicians to decline credit for numbers when they look good, but in the case of demonetisation, waiting a bit before claiming “no adverse impact” would be more fruitful.

The November post-DeMo numbers are cause for one cheer, not two or three. Judgment for that will have to wait.