Economic Package 2020: How The Emergency Credit Line Can Be A Boon To All Businesses

The emergency credit line in the economic package will give a boost to long-pending reforms in agriculture, labour and mining.

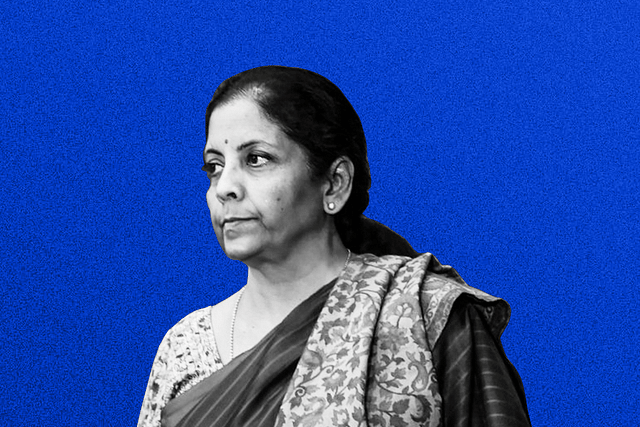

Five days of presentations by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman are now behind us. Clearly, many far-reaching reform measures have been announced – from agriculture to labour to mining. Many of them have been pending for quite some time.

The redefinition of criteria for micro, small, medium and large enterprises to include the book value of investment (now enhanced) and sales turnover removes the disincentive for their growth. Its impact could last decades.

The prospect of re-imagination of government ownership of banks under the promised new public sector enterprise policy is tantalising.

Attempts to remove the yokes that bind the farmers to intermediaries are overdue. Some states have taken the lead already and the Union government is nudging them.

Indeed, these agricultural reforms must be implemented properly, without dilution of intent in practice and without much loss of time too.

If farmers are able to sell whatever they produce, whenever feasible, wherever (unrestricted inter-state movement) and to whomsoever (no export restrictions please) at whatever price the market is willing to pay, then in due course, supply of electricity at zero cost can be withdrawn and agricultural income can cease to be exempt from tax.

From the perspective of providing short-term support to businesses, the emergency credit line to businesses, principally to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) is an important element of the ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ package. It awaits critical details.

While each enterprise is eligible for 20 per cent of its combined outstanding of term loan and working capital loans, what is not clear is whether the twin criteria of existing loan outstanding (less than Rs 25 crore) and sales turnover (less than Rs 100 crore) have to be satisfied or one would suffice.

Second, the pricing of the loan has to be reasonable. It would defy logic for the banks to charge the usual interest rates on loans that will carry a 100 per cent credit guarantee.

The Finance Minister’s package promised that interest rates would be capped.

Third, banks would not lend to borrowers with negative net worth even if they had been current on their loans.

Therefore, losses incurred by enterprises since 1 April should be allowed to be treated as deferred revenue expenditure (DRE) rather than them eroding net worth.

Mere edicts to banks will not suffice as banks would be still wary of being questioned later for lending to borrowers with negative net worth.

Units operating in red zones, in particular, will incur losses and may become ineligible for these loans.

Therefore, accounting standards may have to accommodate a ‘Covid amendment’ to enable losses to be treated as DRE.

There is no emergency credit facility on softer terms offered to businesses with loans outstanding exceeding Rs 25 crore or having sales turnover exceeding Rs 100 crore.

The presumption is that banks would be willing to fund them.

Given the anaemic bank credit growth, that is a leap of faith. A comprehensive analysis done by CRISIL on the 30 April (“Covid-19 impact on economy, corporate revenue and profitability”, 30 April 2020) shows that 70 per cent of the 40,000 companies they had examined had enough cash only to cover up to six months of employee costs.

Their cash and bank balances did not include other fixed costs. Such companies only accounted for only 6 per cent of the total revenue of Rs 130 lakh crore and 8 per cent of the total employee cost of Rs 11 lakh crore for their universe of 40,000 companies.

With the total outstanding to MSME sector being Rs 16.4 lakh crore, the government’s emergency credit line could be as high as Rs 3.2 lakh crore.

The employee cost commitment of companies with sales turnover of up to Rs 100 crore would come to only Rs 88,000 crore as per CRISIL calculations.

Therefore, this emergency credit line could cover a much larger universe of enterprises, and the terms offered to larger companies could be different, and also 100 per cent credit guarantee may not be needed for those borrowers.

Some of the money could also be used to provide assistance to the travel, tourism and hospitality sector that is badly hurt by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The government of India has done well to include many essential reforms, to allow states to borrow more, to expand National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) coverage and yet to keep its explicit on-budget spending around 1 per cent of gross domestic product or GDP (exact portion would depend on how much additional capital the government would provide to the credit guarantee trust fund for micro and small enterprises).

More spending may be needed if Covid-19 lingers.

Therefore, on balance, a prudent and smart balancing act has been pulled off. The crisis has been used to usher in some meaningful reforms.

Among seven countries in Asia for which data on net equity inflows is available, India is the only country to enjoy net positive inflows from foreign institutional investors in the month of May (data up to 15 May). For the package to reinforce that trend, three things need to happen.

As outlined above, there is scope for improvement in one of the cornerstones of the package.

Two, the speed of execution and clarity of instructions are important ingredients for success.

Third, real-time monitoring of implementation of the package and reporting to the public would be sound governance and also a sentiment booster.