How A Pact Signed By UPA Government With ASEAN, Malaysia Could Now Haunt Oilseed Farmers

A comprehensive economic cooperation agreement between India and Malaysia (MICECA) will come into force from the New Year.

A lowering of import duty, as per the agreement, could impact the domestic oilseeds sector, starting with the farmers.

In November this year, import of edible oils, most of which is used for cooking, dropped 9 per cent to 1.13 million tonnes (mt) against 1.25 mt in the same period a year ago. This, despite prices for crude palm oil ruling at an average $472 a tonne landed price in Mumbai against $510 currently.

In fact, last season (November 2017-October 2018), edible oil imports dropped to 14.51 mt against 15.07 mt the previous season. The drop was despite prices for all oils falling continuously from November.

For example, landed prices of crude palm oil have dropped from $703 a tonne in November 2017 to the current level. Similarly, landed prices for crude soybean oil have slid from $839 to $682. Crude sunflower oil rates have dropped to $689 from $811.

Thanks to the higher duty on import of edible oils, domestic prices of oilseeds and indigenous cooking oils are ruling a little higher compared to the same period a year ago. The Narendra Modi government took a few measures this year to protect the interests of oilseed farmers.

In March this year, the central government raised the customs duty on crude palm oil to 44 per cent from 30 per cent while that on refined palm oil and RBD palmolein to 54 per cent from 40 per cent. In June, the import duty on other crude soft oils like soybean was raised to 35 per cent while on refined oils to 45 per cent.

But all that could change, come 1 January 2019. One of the reasons given for the drop in edible oil imports in November was that a comprehensive economic cooperation agreement between India and Malaysia (MICECA) would come into force from the New Year.

Under MICECA, import duty on palm group of oils should be a maximum of 40 per cent for crude palm oil and 45 per cent for RBD palmolein and refined palm oil from 1 January 2019. This means, the landed price of palm group of oils could be cheaper in view of the lower duty.

Importers may have taken a risk as there are chances of prices rising. The fact is that prospects of a rise in edible oil prices aren’t bright as long as crude oil prices rule low. Currently, prices of Brent crude oil, the benchmark for India, are ruling below $55 a barrel.

When crude oil rules low, commodities that are seen as an alternative to it or its derivatives also drop. For example, palm oil prices had ruled over $800 a tonne when crude oil prices ruled around $100 a barrel. This is because edible oils can be used to produce biofuels like biodiesel.

Similarly, natural rubber prices also flared up since prices of synthetic rubber, a derivative from crude oil, shot up. In short, lower crude oil prices keep prices of other commodities, starting from wheat, under pressure.

Therefore, importers have played a strategic game expecting crude oil to rule below $60 a barrel, which in turn could keep edible oil prices lower. That’s the reason why they imported a lower volume of palm group of oils in November – 0.69 mt against 0.71 mt and plan to ship in more into the country from January onwards.

There is another dilemma on MICECA. India has signed a free trade agreement (FTA) with the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). Under this agreement, import duty on crude palm oil has been capped at 40 per cent and that of refined palm oil and RBD palmolein at 50 per cent from the New Year onwards.

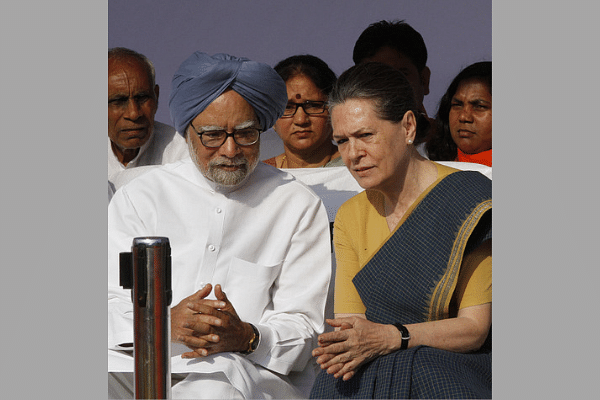

Though the framework for the ASEAN FTA was signed by the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government in 2003, it was finalised on 13 August 2009 when the Manmohan Singh-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government was in power. The FTA came into force from 2010 with various deadlines for reducing the duty for a slew of commodities leading up to 31 December 2019.

The problem with going ahead in implementing either MICECA or the ASEAN FTA by lowering import duty is that it could impact the domestic oilseeds sector, starting with the farmers.

MICECA was also signed by the Manmohan Singh government in 2010 and it came into force from 2011. This, like the ASEAN FTA, has got various deadlines to meet in lower import duties and, as per this, the levy on crude and refined palm group of oils will have to be lowered from 1 January 2019.

The problem in implementing ASEAN FTA and MICECA deadline on the palm group of oils import duties is that it could have a deleterious effect on Indian farmers, particularly those who have cultivated oilseeds.

Currently, rates of oilseeds like groundnut and soybean are hovering around the minimum support price (MSP) levels fixed by the centre. For groundnut, the MSP is Rs 4,890 a quintal and prices are ruling at Rs 4,950 in Saurashtra in Gujarat, according to data from the Solvent Extractors Association of India. Prices of soybean at Indore, the hub of the oilseed in the country, are ruling at Rs 3,400 a quintal at par with the MSP.

Come the New Year, and when a new duty regime comes into effect, the prices of these oilseeds will come under pressure. Not only the oilseeds but also prices of rapeseed/mustard, a rabi crop for which sowing has just gotten over, will come under pressure.

This will see groundnut farmers in Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu, soybean growers in Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat, sunflower farmers in Karnataka, and rapeseed/mustard growers, primarily in Rajasthan, facing problems of lower prices.

The amusing aspect of this development is that this will affect non-Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled states like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Andhra Pradesh more that BJP-ruled ones like Maharashtra.

There is another angle to this development. Both the MICECA and ASEAN FTA were signed by the UPA government led by the Congress.

While the principal opposition party – the Congress – is now talking loudly about farmers’ benefits, it has actually done them a harm by signing these agreements that could affect them when it was in power back in the day.

No doubt, India imports nearly two-thirds of its edible oils demand and this could have engaged the minds of those in the government at the time. But then, governments over the last two decades have been talking of encouraging and increasing oilseed production.

Governments have been coming up with various initiatives in the budget to encourage farmers to take up oilseed cultivation. When this is the fact, why is that the Manmohan Singh government failed to anticipate the situation that we are facing now?

When this is the case, how did the Manmohan Singh government, which waived farm loans in 2008, sign trade pacts that affects its farmers? There is also some oversight in signing the ASEAN FTA and MICECA.

Under ASEAN FTA, India could cap the customs duty on crude palm oil at 40 per cent and that on refined palm oil and RBD palmolein at 50 per cent. But under MICECA, the duty on refined palm oil and RBD palmolein is capped at 45 per cent.

The problem is, which will the current government implement? Not just the farmers but oil mills, small and large, solvent extractors, and refining mills will be impacted by this lower duty. More importantly, if the duty is fixed as per MICECA, refined oil mills will take a big hit since a lower duty difference of five percentage points between crude and refined edible oils will make the import of refined oils lucrative.

There have been so many slip-ups under the Congress-led UPA government that most of them have gone unnoticed. Parties and industries that have stakes had raised these issues from time to time but in vain.

Having said that, what are the options left before the Modi government now, especially to ensure that farmers don’t suffer? The centre, probably, can continue its practice of coming out with the tariff rate – the reference price for customs to levy import duty – every 15 days. Only that, it will have to ensure that the tariff rate will be higher enough to protect domestic farmers.

It will be difficult for India to seek some re-negotiation in this area, but nothing can stop the Modi government from resorting to non-tariff barriers. This could be on the grounds of environment since we see some non-governmental organisations carrying out a campaign against palm oils.

India can also look at aspects like non-cooperation by Malaysia in getting T Ananda Krishnan for investigation into the Aircel-Maxis deal or repatriating Islamic hardliner Zakir Naik, accused of promoting terror and hatred in India.

The Mahathir Mohamad government in Malaysia is known to be more friendly with senior Congress leader Sonia Gandhi. He had refused to help India in getting the late Ottavio Quattrocchi, the prime suspect in Bofors scandal, when his extradition was sought by the Vajpayee government.

Manmohan Singh, in press conferences, has always said policies of the government were on the advice of the Congress party president. At that time, it was Sonia Gandhi. Did he give in to Malaysia’s demand because Mohamad had helped his party leader in not handing over Quattrocchi?

Options are there for the centre to consider these steps to help farmers. The Modi government has to come up with some initiative that can undo, at least temporarily, the damage that MICECA and ASEAN FTA can cause to oilseed farmers.