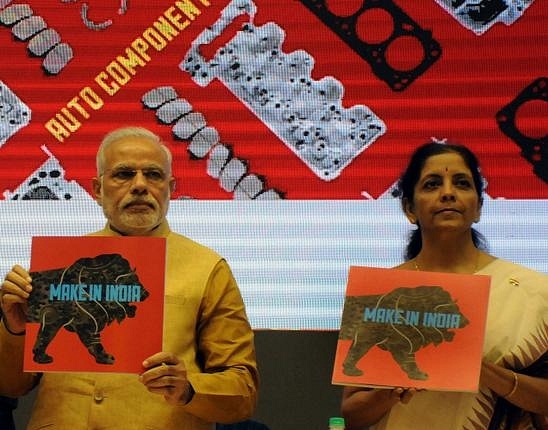

How Does one ‘Make in India’, Anyway?

Make in India campaign must advance steadily from a successful communication tool to an efficacious reforms mechanism

The government’s “Make in India” campaign has been met with much brouhaha from foreign investors, diplomats, journalists, industry leaders and Modi’s own ministers. The Prime Minister’s messianic will to transform the manufacturing sector of India to a world-class production hub in order to revive the languishing economy appears far-fetched at this juncture. At the launch of the campaign in October, business leaders who were allowed to put across their views from the podium espoused Modi’s initiative and corroborated this dream. Arguably this is an icing on the industrialisation cake. Such a consensus from the principal actors in the market was a good sign, but it was never enough reason to be happy about. Alas, the cake is yet to be well baked!

The “Make in India” initiative can undoubtedly be credited for its excellent communication platform and for putting various investor-friendly policies and perspectives in one place. This is a good first step but, since the campaign launch, the government has been slow in firming up some vital measures crucial to get our hamstrung economy rolling.

In an interview to one of India’s leading newspapers, former Union Minister Arun Shourie of the BJP drew an analogy on Modi government’s style of functioning. He says sincere efforts are being made and they may yield results, but as Akbar Ilahabadi said, “Plateon ke aane ki aawaaz to aa rahi hai, khaana nahin aa raha (One can hear the sound of plates, but the food hasn’t arrived yet).” To ensure that the food is served before the guests leave, the government needs to take up bold measures and be wary of other nuances in policy implementation.

Bottlenecks

Foreign Direct Investment in railways has been in a limbo since the “Make in India” campaign was launched. According to new Railways Minister Suresh Prabhu, the sector requires investments of up-to $100 billion over the next 3-4 year horizon to improve its services and mend its operating ratio. The minister is keen to be the harbinger of change by bringing in 100% FDI to refurbish the ailing sector. This is a welcome first step; however, several structural impediments need to be dealt with before we see any discernible change in foreign investment.

In the past, private operators have stayed away from investing in freight lines because of the inefficiency in approval processes. Taking the example of the port-railways linkage, a shortage in freight lines have meant over-crowding at ports, which, in turn, has led to delayed deliveries of coal to power plants and iron-ore to steel plants. Even if the government is able to rake in private investors to solve this problem, it still does not guarantee a solution for the smooth movement of cargo across freight lines. The state owned railways still controls the provision of goods wagons. This has drawn much criticism by private port operators; they claim that the government has failed to provide enough wagons to service the growing needs of extra cargo.

Taking cognisance of the stringent exit rules in the construction sector which has been one of the key deterrents in attracting FDI, the Government recently relaxed FDI rules for the sector. The rules are deemed to make it easier for investors to enter the construction market, sell assets or transfer their stakes and repatriate proceeds even before the completion of a project. Mere change in FDI rules might not segue into investor confidence till the time hurdles like single-window clearance for construction projects are taken up on a priority basis. From June, 2013 to May, 2014 period, India hit the nadir in at least two categories of the Ease of Doing Business published by the World Bank; it stood 184th in the ‘Dealing with Construction Permits’ category and 186th in ‘Enforcing Contracts. While the government has promised affordable housing to all, the prevalence of a multi-agency approach to project approvals is counter-productive as it adds nearly 30-40% to the cost of constructing projects.

The FDI in the defense sector is still capped at 49% composite cap. This means that no foreigner can have a governing share of any joint venture in India. According to KPMG, a global consultancy firm, this is a big disappointment as the sectors won’t see any technology transfer at this level. There has been no FDI in defense since the last budget was presented. The government must consider at least 74% of FDI in defense to ensure knowledge transfer and give sectors like metalworking and ceramics a fillip.

Education and skill upgrade

In order to give the manufacturing sector a stimulus, amongst other things, education and skill up gradation are key ingredients. Due to inadequate skills of workers, manufacturing jobs in India are mainly low quality. This means that workers are mainly employed in the micro-small medium enterprises and earn monthly wages, which are just above the poverty line and derisory for a decent subsistence. Moving up the value chain will require technical upgrade of skills and better quality of education.

Arvind Panagriya, professor of Economics at Columbia university in a recent article on Make in India, points to the requirement of decades of first-rate higher education before we can get our workforce to do what the American workforce can. For now, the bulk of services jobs are low-paid and in the informal sector. According to him, the 2006-07 National Sample Survey found that, of the 15 million services enterprises, the largest 626 produced 38 per cent of the services output but employed barely two per cent of the workers in the sector. That the Modi government recognised skill development as one of the important areas of reforms to give an impetus to ‘Make in India’ is not a solution for the perennial problem. We need to kick start the process of refurbishing the national skill development policy in India, which is still in the doldrums. Similarly the government needs to do the herculean task of rotating the wheel of reforms in both basic and higher education, which have been pending for a long time.

Land Acquisition:

One of the biggest hurdles to industrialisation is land acquisition. Since independence, land in India has been plagued with issues of history, politics, law and identity. In the context of “Make in India”, land is also an essential element of development of industrial corridors and SEZs, which are touted as key for propelling industrialization. The recent plan of the government to take the ordinance route for pushing across key economic reforms including the Land Acquisition bill is a worthy step.The government will do justice to the swathe of un-allotted or unproductive industrial land across India by making necessary amendments to Land Acquisition Act.

However it is equally important to ensure that the problem of shortage of industrial land is solved by better managing the existing land resources held by state authorities, developing land banks faster and ensuring that allotments of lands made to businesses are more transparent and put in place a continuous monitoring mechanism to prevent squatters and speculators taking unfair advantage. Thanks to a recent November 2014 study undertaken by NDTV, which provides anecdotal evidence of such instances and throws light on these hurdles in more detail.

It will be in Modi’s interest to plug these fissures before they further imperil the manufacturing sector and cause disquiet in the principal agents. Moreover, the Make in India campaign must advance steadily from a successful communication tool to an efficacious reforms mechanism. It is about time that the country’s manufacturing sector pulls up its socks to support India’s optimistic growth trajectory and guarantee jobs to the millions of unemployed youth.