Keeping Petro-Fuels Outside GST Is Politically Sensible; It Helps Reduce Centre-State Friction

In the political economy of an increasingly federating country, petro-fuel taxes are a safety valve for revenue frustrations.

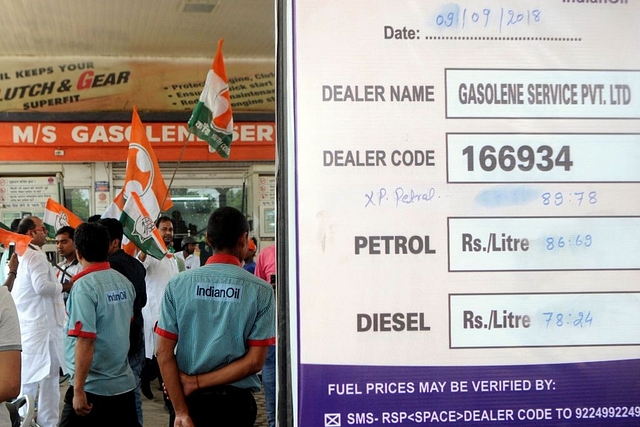

With global oil prices weakening, the oil marketing companies are passing on the reductions to petrol and diesel consumers, especially since this is election season. It is quite possible that both Centre and states will seek to recoup lost revenues once we move back to post-election normality, though the window is narrow till about January-end. After that, we are back to another big general election season, to elect the next Lok Sabha and some state assemblies (Odisha, Andhra).

Given the political nature of pump pricing in petro-fuels, and also the huge revenues generated for both Centre and states, the realistic thing to do is simple: create an oil pool account, where some part of the excess taxes collected when prices are down can be used to subsidise petro-fuels when global prices start soaring, as they did till a few months ago. It may, in fact, make sense for both Centre and states to maintain separate oil pool accounts, so that the yo-yoing nature of global oil prices does not immediately dent their fiscal maths.

The Economic Times, in an editorial today (7 December), suggests that “we should aim for stable tax revenue from petro-fuels, tax rates moving down when oil prices go up, and vice versa. By how much the rates should go up or down should be determined by an algorithm, leaving no discretion with governments.”

The broad idea of keeping prices as stable as possible is correct, but when petro-fuels pricing is such a political decision, it is futile to pretend that an algorithm will protect any government from political pressures to cut prices at the wrong time, or raise it at the right time. It is best to let politicians decide how they want to manage this hike and cut in taxes. In fact, the same end – of greater price stability – can be achieved through oil pool accounts, as mentioned earlier. Trying to deal with a political economy problem through a good economic idea does not work.

The real issue is the scale of the bonanza Centre and states get from petro-taxes, cesses and dividends from oil companies. In 2017-18, states and Centre collected a massive Rs 5,53,017 crore from petro-fuels. The Centre collected the larger amount of Rs 3,43,862 crore and the states Rs 2,09,155 crore. But don’t let this fool you in thinking it is the Centre that benefits more. Since 42 percent of all taxes devolve to states, the final collections actually tilt in favour of states by a large margin. After devolution, states get Rs 3,53,577 crore and the Centre’s take is down to Rs 1,99,440 crore. This year should be no different, though both Centre and states have cut taxes, which may be reversed soon.

There is also a suggestion that ultimately petro-fuels should come under the goods and services tax (GST), but this is a pipe dream. As long as these taxes are a huge part of state revenues, there is little chance that any state would want to lose this element of revenue flexibility.

After GST has been implemented, both Centre and states have given up a part of their revenue sovereignty. While the gain to the economy is incalculable at this point, the downside is the GST’s inherent potential for creating political friction between Centre and states, which could escalate if some states see themselves losing out on GST. And, if the composition of the GST Council, now heavily tilted in favour of BJP-ruled states, changes after the current round of assembly elections and the general elections of April-May 2019, all bets are off.

It is best to leave states with the comfort of having some control over their revenues in order to preserve the peace in the GST Council.

True federalism demands that states should have some revenue flexibility, and it does not make political sense to remove even this measure of state sovereignty by bringing GST into the picture. The time to bring petro-fuels under GST is when the share of petro-fuels in state revenues gets normalised – i.e., after the rest of the items already under GST start generating copious amounts of revenue, and states lose their fears of revenue losses or budget flexibility.

In the political economy of an increasingly federating country, petro-fuel taxes are a safety valve for revenue frustrations at the state level. It is not good to remove the safety wall just yet.