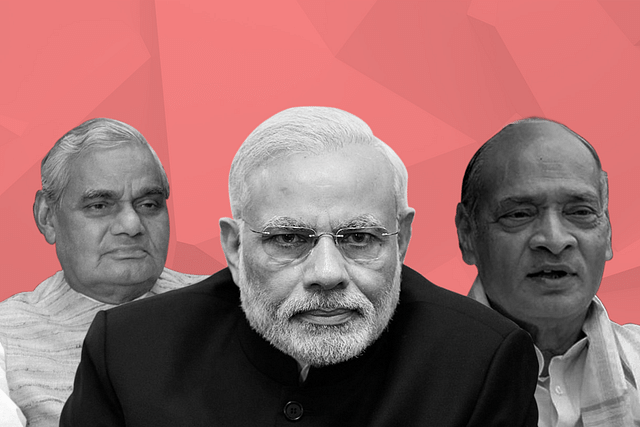

Modi Can Take Reformist Crown Away From Vajpayee And Rao As He Re-Engages With Economy

Neither Rao nor Vajpayee clearly established themselves as anything more than fair weather reformers, but Modi has carried out reforms when no pressure existed.

If Modi can bring forward a legislation that allows for actual privatisation of public sector entities, no one can deny him the title of reformer-par-excellence.

The best economic news we have had in a long time is that the Prime Minister is re-engaging himself with the economy – and its problems. This became clear when the Finance Minister announced a blockbuster tax cut last week that will cost the exchequer Rs 1.45 lakh crore in revenue forgone.

This is not something Nirmala Sitharaman could have done on her own. Nobody, barring the Prime Minister, could have helmed such a bold initiative, even though he remained in the shadows during the announcement.

Some analysts believe that Narendra Modi is an incremental reformer, with little appetite for bold reforms. But this is bunkum. If there is any politician with disruptive reforms in mind, it is Modi. This should be obvious from the implementation of the biggest tax reforms ever seen in Indian history (the goods and services tax), the biggest reform of bankruptcy laws which showed the door to many cronies, and the biggest reform of subsidy deliveries ever seen (through the Jan Dhan-Aadhaar-Mobile route of direct cash transfers).

If, on the other hand, the only yardstick to measure reformist zeal is privatisation or factor market reform, then, of course, Modi can be found somewhat wanting. But even here, his hands were tied by the lack of a majority in the Rajya Sabha during his first term, and the strident campaigns by the Lutyens elite and minority groups to paint him as intolerant, as the man behind the so-called “church attacks” and “lynching” of Muslims over beef.

With his back to the wall on such politically-charged issues, Modi wisely decided, Shivaji style, that bravado on the labour and land market fronts can wait. But incremental reforms did take place, with the Apprentices Act being modified and labour flexibility being introduced through the extension of fixed-term labour contracts to sectors beyond textiles and leather. So even here there has been a forward movement.

Some also believe that Modi in his first term may have been trying to live down the “suit-boot-ki-sarkar” image thrust down his throat by Rahul Gandhi in 2015. There could be some small truth in this, but the larger truth is that Modi wanted to reposition himself and his party well to the left of centre in its first term. The problem all right-wing parties face is that they can be easily stereotyped as being anti-poor if they espouse pro-market and reformist policies.

There is little doubt that Modi sets great store by public perceptions and personal image. This will explain most of his moves in the first term.

If one were to look at his political past, he has reinvented his public persona every five years – roughly to coincide with each term in office. In 2002, he consolidated power in Gujarat by seeking to portray himself as the defender of Hindu identity after terrible riots followed the torching of a Sabarmati Express coach with Hindu pilgrims on it.

But by 2007, he was growing out of this image. He reinvented himself as the growth icon, inviting foreign investment to his state with pro-business policies that culminated in the Vibrant Gujarat show. After this, he made himself accessible to any and all businessmen who needed some red tape to be negotiated in his state.

By 2012, when he began eyeing Delhi, he endeared himself to every global businessman, forcing the hitherto-inimical US and European governments to grudgingly accept him as acceptable. He touted his Gujarat model as one that will deliver China-like growth for India if he became Prime Minister.

But in 2014, after becoming PM, his rhetoric changed. Suddenly, his speeches talked almost exclusively about the poor and the marginalised – the phrase “vanchit, shoshit, peedit” recurs almost in every speech of his. From Jan Dhan to toilet-building under Swachch Bharat, to Ujjwala, Ayushman Bharat and Kisan Samman, the big initiatives were targeted at the small man.

What the “suit-boot-ki-sarkar” jibe probably ensured was to make Modi unwilling to be seen hobnobbing with big business – a practice he restarted only towards the end of his first term. This came when business confidence began to ebb considerably, growth slowed, and the combined effects of bankruptcy proceedings, harsher bank lending norms, and the deflationary effects of Modi’s tax-compliance policies began to bite.

Even in the first 100 days of his second term, when his mandate was expanded by the voter, Modi seemed disengaged with economics, and his government’s first budget was a washout. But, with hindsight, we can say that this was because of the big moves planned on Article 370 and Jammu and Kashmir.

While J&K will continue to absorb his attention going forward, Modi clearly is now making time to engage with the problems confronting the economy. Apart from the big bang tax cuts, the regular and repeated cuts in GST rates, the commitment to privatise Air India and the introduction of two bills that consolidate all labour laws indicate that reform momentum will continue in Modi 2.0.

The only real problematic area is privatisation. All the strategic sales of public sector companies so far have ended up with other public sector entities buying them (HPCL by ONGC, REC by PFC, IDBI Bank by LIC). The latest move involves the sale of the government’s majority stake in Bharat Petroleum (possibly to Indian Oil).

This is not only wrong, but problematic, as this kind of disinvestment amounts to nothing more than transfer of money from one pocket of government to another.

This is really the big test: if Modi can bring forward a legislation that allows for actual privatisation of public sector entities – it will require changes in various acts used to nationalise entities like banks, insurance, steel and petroleum companies – no one can deny him the title of reformer-par-excellence.

The only reason reform-minded economists want to deny him the label was Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s privatisation gambit. What they forget is that the Vajpayee era privatisations were done illegally by Arun Shourie. The courts said that companies nationalised through a law cannot be privatised without repealing those laws. This is what Modi has to do now.

One hopes he confronts this reality sooner than later, when the honeymoon period for Modi 2.0 is about to end. If he can get this done in the next 100 days, he would have snatched the reformist crown away from P V Narasimha Rao and Vajpayee.

But neither Rao nor Vajpayee clearly established themselves as anything more than fair weather reformers. Rao did so as the country faced external bankruptcy in 1991, and Vajpayee did so as India faced US sanctions after the Pokharan 2 nuclear blasts. Modi alone has carried out reforms when no such pressure existed.

In some ways, you could say, he is the real committed reformer – with the solitary exception of a commitment to privatisation. This P word is what Modi needs to internalise.