The 2019 Elections Are Tricky for BJP, But Invoking 2004 Will Not Help

If the economy continues to build on the momentum and the stock market rebounds strongly, the narrative will shift quickly, naysayers within the NDA will melt away, and opposition bonhomie will start to falter.

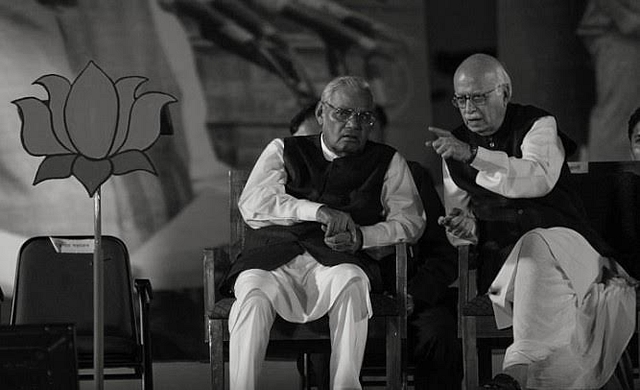

The ghost of 2004 haunts Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supporters, who see its spectre looming large again. Ever since Narendra Modi became Prime Minister in 2014, every minor setback has been seen as the road leading to another 2004-like debacle. To be sure, the BJP faces a tricky pitch in 2019, as I have argued. Nonetheless, analysing 2019 through the prism of 2004 is likely to lead us astray. In 2004, “India” may have been shining but “Bharat” was clearly struggling and voted National Democratic Alliance (NDA) out. Now, India is not shining, but whether Bharat is doing well cannot be discerned from a discourse that is urban-centric and that tends to project rural experience from the concerns of urban India. What we do know is that rural consumption is gathering steam, monsoons are forecast to be normal in 2018, and the government has increased minimum support prices.

Moreover, the present NDA government’s efforts have been heavily focused on rural India and the poor — electrification, toilets, financial inclusion, direct benefits transfers, etc. Whether these have made a tangible enough difference to tilt the outcome in 2019, remains to be seen.

While there are some similarities between 2004 and the present, the differences are substantial.

The Economy

My parsimonious model of the election forecasting suggested that the 2004 loss was hardly a surprise and that the NDA’s reelection prospects in 2019 appear to be much better, albeit still challenging. The five-year growth rate (I am using a five-year period because that is the normal term for a government) in 2004 was actually one of the weakest in the post 1995 era. In contrast, the present government appears to be in better placed. More important, there is still more than a year left till the elections, and the economy appears to be accelerating.

Industrial production, capital spending, car, truck, and two-wheeler sales are surging. Last but not the least, after the massive credit contraction following demonetisation and the rollout of goods and services tax (GST), credit growth is now accelerating at its fastest pace since 2006.

India vs Bharat

The biggest difference between 2004 and 2019 is the contrasting experiences of English-speaking urban denizens — call it India —and the rest of the country — call it Bharat. The Shining India campaign of 2004 reflected the experience of ‘India’ not ‘Bharat’. In the early years of the new millennium, India’s software exports were booming. After the sharp decline following the Dotcom bust, software exports surged, as outsourcing was stepped up. The result was a jobs boom — especially the kind of jobs that are desired. India Shining was not fake.

However, the vast majority of Indians do not work in software industry or finance. Bharat was reeling from a drought in 2003 that followed on the heels of a severe drought in 2001. Rural incomes were growing at half the current pace. In addition, the poverty rate had stagnated for the five years from 1999-2004, showing that the vast majority had not shared in India Shining.

In contrast to 2004, India is not shining now. Job creation in the formal sector remains weak and the software boom is a distant memory. However, rural incomes, rebounding from the twin shocks of demonetisation and GST, are growing at twice the pace of 2004. We have had two normal monsoons and the 2018 one is slated to be another normal one. In fact, rural spending has been accelerating in 2018 and driving the national figures. With the increase in minimum support prices in the latest budget, rural incomes will receive a further fillip. Bharat may not be shining but it is not in the doldrums it was in 2004.

Since coming to power, the Modi government gradually changed tack toward a focus on rural areas and the poorer segments of society. There has been a massive push to electrify rural areas, provide cooking gas, and eliminate open defecation. These is a huge change in the quality of life, not necessarily captured in gross domestic product nor by the media, which tends to focus on the concerns of the urban elite. In addition, direct benefit transfers have reduced pilferage and improved delivery of subsidies.

Meanwhile, the combination of Aadhaar and Mudra have made loans accessible to marginal entrepreneurs — from the pakora seller onwards — who otherwise would have had to pay usurious rates to the moneylender. Perhaps, these are beginning to bear fruit as the demonetisation shock wanes.

Conclusion

Purely from an economic perspective, the NDA is on a much stronger wicket than in 2004. Perhaps, the economy will be trumped by other factors — opposition unity, discord in the NDA, etc. However, there is still a long way to election. If the economy continues to build on the momentum and the stock market rebounds powerfully, even “India” will turn, the narrative will shift quickly, naysayers within the NDA will melt away, and opposition bonhomie will start to falter. To use a Ravi Shastri cliche, the game is evenly poised and all three results are possible.