The Many Problems With Libra, Facebook’s Cryptocurrency Offering

The cryptocurrency offering by Facebook is intended to boost its appeal across the globe, especially among developing nations.

But the company will have a lot of convincing to do if its currency has to be perceived as safe and trustworthy.

A series of data sharing scams such as the one involving Cambridge Analytica have eroded Facebook’s credibility in recent times.

Facebook, often, comes across as a paranoid rich parent that is constantly in need of attention from its kids, or in this case, over 2.38 billion users across the globe. Thus, it keeps going out of its way to offer the fanciest of gifts in order to lure users towards the platform. This time, it a cryptocurrency termed Libra.

Before diving into the problems of this cryptocurrency, a short understanding of Facebook’s business ideology is warranted as that is the underlying force behind any innovative offering from the company.

Mark Zuckerberg bought Instagram (in 2012) and WhatsApp (in 2014) for a total of $20 billion dollars when Messenger and Facebook could not keep up with the changing user trends.

When Snapchat turned down an offer of $3 billion from Facebook in 2013, the latter simply added similar functions to its recent acquisition, Instagram. Eventually, functionalities similar to Snapchat could be found on Instagram, Messenger, Facebook, and WhatsApp.

The focus, across the decade of 2010, was on buying out the potential competition or rendering it pointless in order to ensure that the user was not able to escape the Facebook ecosystem.

However, Facebook isn’t the only paranoid digital parent out there, for an array of companies are now fighting for users’ attention, and this competition has intensified since 2017, the year Facebook hit two billion active users.

What keeps any social media network relevant is users’ time and interactions. The time invested and engagements initiated by a user ensure that more people join the network over a period of time. Simply put, users create more users, and this attracts advertisers. For Facebook, that is the key.

Today, advertisers have media streaming services, marketplaces, and other digital platforms to advertise which poses a challenge to Facebook’s traditional revenue model. For a network that hosts more people than the population of the American and African continents, there is visible desperation to find relevance in the decade of the 2020s.

Our global population is 7.6 billion. 5.1 billion people have mobile phones, 4.3 billion people have an internet connection, 3.4 billion people are on some social network, and 3.2 billion people on these social networks have access via mobile. At 10 per cent, the Asia-Pacific region is the second fastest growing in the world in terms of the number of users being added on an annual basis. The Middle East, with 11 per cent, is the fastest.

Thus, even at a 2.38 billion user count, there is a huge market for Facebook to trap, and this is where Libra comes into play. Targeted towards 1.7 billion individuals without access to formal financial systems, Libra aims to transcend borders, socio-economic divisions, and monetary restrictions that constrain the use of financial systems in and across nations.

The 1.7-billion figure in the released white paper is merely a paper stunt for Facebook, which would look to use this payment system as a means of increasing its user count by a hundred per cent by 2030 to more than 4 billion.

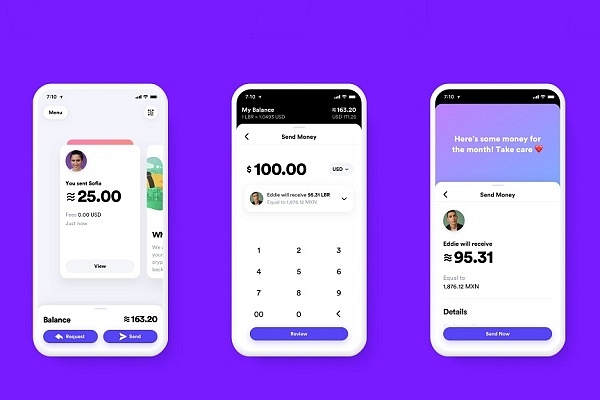

Libra, for Facebook, would work on two fronts. One, it will make the social network relevant to the existing 2.38 billion users. Two, it will use the payment system as a motivator to get more people to use Facebook for the first time.

While at this point, there is no clarity on whether a Facebook account would be mandatory to use Libra, one can assume that the company shall not shy away from going for it, given how they made the use of Messenger necessary for using Facebook messages on mobile.

The market for Libra would come from developing economies of the Middle East and South-East Asia. With China out of the equation, for Libra to work, the major numbers would have to come from India. Today, Facebook has over 250 million of its 2.38 billion users from India.

The path to 1.7 billion unbanked users goes through at least 200 million Indians with no upper limit. Facebook needs India, and that is why we must be concerned. The Reserve Bank of India, along with other regulators, must counter the obvious flaws in the Libra programme.

One, it is the nature of the cryptocurrency itself. Facebook may term Libra a cryptocurrency, but it is a mechanism to move currency around, similar to what we can do with Paytm, the difference being one can use Libra across nations. Also, with Libra being backed by a stable currency and open to exchange at the local prevailing rates, the question remains as to how Libra will work with regulators.

Two, the storage. Essentially, a cryptocurrency, for instance, bitcoin, could be stored in two ways. Firstly, it could be bought through an account on a regulated entity. Kraken, Coinbase, Bitworth, to name a few, were go-to crypto-exchanges for users to engage in the purchase and selling of bitcoins. Users could also store their bitcoins with these exchanges through their own accounts, given most of them were regulated by the governments.

Secondly, the method of cold storage could be used to store a bitcoin. The keys of the bitcoin could be stored on a printed piece of paper, in a flash drive, or any hardware component. This method gave the access authority to the user.

Now, if a user was convicted for any reason, they would lose their account on Coinbase (or similar apps) and thus the bitcoin, if the law enforcement agencies sealed the user’s assets. However, if a user lost the keys of the bitcoin in cold storage, the bitcoin was forever lost.

With Libra, there is no such clarity. Even though it can be exchanged for local currency, there is no clear mechanism on how it could be stored. Could one store Libra across multiple accounts, and will these accounts be under any regulation, or will users have the option to store their Libra in the cold storage manner, or will the use of Libra bind a user to a social media account are few of the unaddressed issues of this programme.

Three, the white paper states that the Libra Blockchain is pseudonymous and will allow users to hold one or more addresses that are not linked to their real-world identity. This opens up a Pandora’s Box of problems. Given the addresses or accounts are not necessarily required to be linked to a real-world identity, what identity would a Libra account require?

Assuming it is a social media or email account, for no government or private sector issued identity ensures such anonymity, how on earth will it be regulated? Can a separatist in Kashmir use Libra to sponsor acts of terrorism somewhere in India with funds they received from the Middle-East, with all three accounts linked to a false email? Can someone in Syria send funds to someone in Europe as a payment to crash a van into a crowd of evening visitors to a cafe using falsified social media accounts? Can an unlawful organisation use multiple Libra accounts across the world to further its interests?

Even if Libra’s digital trail is accessible to the governments, in most cases, it will be hard to track, for the phones or devices used to create or access Libra accounts could be easily disposed of. In many aspects, Libra is a money launderer’s dream and a regulator’s worst nightmare.

Four, even though Facebook promises to keep the social and private data separate with the creation of Calibra, a regulated subsidiary that shall enable services on the Libra network, the line of separation is ambiguous and too good to be true.

Libra is currently backed by founding members that include the likes of PayPal, Visa, Mastercard, eBay, Uber, Spotify, Vodafone Group, and renowned venture capitalists that have interests in countless companies across the globe. At some point, financial data from Calibra would be shared with these companies as Facebook did with social data. What if, somewhere down the line, the social and financial data is sold together?

Five, the mere idea of a social network with access to financial instruments threatens the creation of a surveillance state. The white paper, at various points, affirms that the Libra network shall allow other companies, founders or otherwise, to offer services. This opens up opportunities for companies involved in micro-financing, insurance, credit offers, and much more.

However, the linking of social media accounts for users to access digital loans is a common phenomenon. Therefore, expecting the same on the Libra network is not premature, thus rendering the line of separation between Calibra and Facebook pointless.

This is one front where social and financial data will merge, and if the same data is accessible to the government or private entities, the creation of a surveillance state will only be a step away.

What if, in the future, the access to financial services on the Libra network is differentiated on the basis of what a person posts, shares, follows, or likes? What if the differentiation on the Libra network is then mirrored on the formal financial and other networks too?

Six, the redundancy. Assuming a regular user signs up on Libra with their real-world identity. In this case, the whole idea of using the currency shall become redundant. For a nation like India where BHIM-UPI has enabled the easy way of transactions, the idea of using another currency sounds redundant and futile.

With the JAM (Jan Dhan, Aadhar, and Mobile) Trinity in play, previously unbanked individuals are now gaining access to formal financial instruments. Already, there are over 350 million Jan Dhan accounts in India, amounting to an account for every family. In such a setup, Libra sounds pointless, for not many would be willing to risk the minor volatility in local exchange rates when they can transact using UPI. There goes the 200 million market for Facebook’s Libra.

Lastly, the lack of trust that Facebook now inspires. According to a December 2018 report in the New York Times, Facebook had shared private user data with Microsoft’s Bing, Spotify, Netflix, Yahoo, and Amazon. Also, the Cambridge Analytica scandal last year showcased how easy it was to get around the privacy metrics on Facebook.

The lack of trust is what shall hurt Libra the most. Given the network will include services and members like Uber (or similar on-demand apps), Spotify (or similar music and media streaming apps), Vodafone (or other telecoms), Visa and Mastercard (or other local finance partners), the users will be worried if their financial data could be used with their social data to profile them.

With no government regulation to control the flow of data, as it currently is in India, the concern would also be around data localisaton and selling of private data to third-parties,

The same amalgamation of data could also be used by advertisers to not only target users on the basis of what they like, where they are located but also on what they can or cannot afford. This socio-economic profiling would be the end of digital privacy, facilitated by a company that offered private social networking and financial inclusion in the first place.

Even in its theatrical sincerity, Facebook’s Libra programme raises more concerns than the causes it addresses.

Going ahead, Zuckerberg, along with the minds behind Libra, would have to reason out with regulators across the globe to find acceptance for their currency. If the social media giant wishes to roll out this currency by the second half of 2020, it has a lot of ground to cover on the tech front and more importantly, on the ethical front.