D. V. Gundappa Always Worked For The Public Good

Reposting this as a tribute to Padma Bhushan Dr. D. V. Gundappa on his 129th birth anniversary.

By Masti Venkatesha Iyengar

D. V. Gundappa, whom the country lost recently (7-10-75) was a great figure in the public life of the Mysore State. He was eighty-seven years old when he died. About sixty-seven years of that life he had spent in serving the population of the State as a journalist, social worker, litterateur and in other capacities, and attained an eminence which made him one of a handful of Mysore people whose names were known all over India.

D.V.G., the convenient abbreviations by which friends always referred to him, came of a family of middle-class Brahmins of the Mulbagal town in the Kolar district of Karnataka. His father, Sri Venkataramanaiya, was a school teacher at Devanahalli when this son was born. D. V. in the name stood for Devanahalli Venkataramanaiya.

Early Education

Gundappa’s education followed the pattern of the education of most of us of that generation. Early education in a village or town; high school education in a bigger town, generally the district headquarters station. The end of the secondary stage, corresponding to what is now known as the SSLC, was the matriculation examination; a hurdle which only small numbers could cross. Failure in one subject meant failure in the examination. Many people failed because they could not cope with the mathematics part of the studies. It would appear that Gundappa was in this class. He failed in the examination and could not proceed to college.

As we now know, Gundappa’s predilections were towards the Humanities. It is no wonder that he could not get on in mathematics.

Barred from higher education, Gundappa had to think of some career in his life. Inclination took him to journalism. There was, in those days, a paper in Bangalore of the name Mysore Standard. The Editor was one M Srinivasa Iyer. Gundappa got into touch with this journalist, and began life.

A Fearless Critic

In reminiscential writing published in the last few years, Gundappa gave some idea of the atmosphere in which he had to work. Journalism was by no means a prosperous profession and a free-lance had to feel grateful if he could make enough for ordinary living. Gundappa passed through some years of hard apprenticeship and started a bi-weekly English paper of his own named Karnataka in 1913. In an article which he contributed to the centenary volume in honour of Sir M Visvasvaraya in 1960, he described the manner in which he got the permission of the Government to edit the new paper.

Gundappa was about twenty-five years old at the time, but he was full of self-confidence, and, though not a matriculate, very well read for his years. By nature he was indifferent to personal gain or loss. He also cared little for the smile or frown of men in authority. These traits seem to have been natural to him and made him a sound critic of the administration. The result was that in the next few years he came to be recognised as a reliable representative of healthy public opinion.

Inspiration from Gokhale and Mazzini

Gokhale and Mazzini were the great names which inspired Gundappa to clean and selfless service in those years. Gokhale’s examination led him to equip himself fully before attempting any task. He thus trained himself to be sure of his facts before making statements and was formidable whether as colleague or opponent.

Meanwhile, in 1915, when Gandhiji visited Bangalore, Gundappa was one of the leading citizens of the city who received the Mahatma and honoured him. Gundappa would, in any case, have withstood any temptation to swerve from the path of truth. Contact with Gandhiji confirmed him in this attitude.

About this time (1915) he and his friends started an Institute of Public Affairs in which competent persons could gather and discuss matters of serious import. Due, no doubt, to Gundappa’s desire, this Institute was called the Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs.

Karnataka did not prosper. Gundappa made it into a monthly called the Karnataka and the India Review of Reviews. This monthly also did not prosper. The Government of Dewan Sir Albion Banerjee asked Gundappa to edit the Kannada mouthpiece of the Economic Conference called Artha Sadhaka Patrike. Gundappa agreed, proposing that he should make the journal partly literary. The name was to be Janajeevana and Artha Sadhaka Patrike. The Government agreed. This venture was of short duration. Gundappa would not tow the line the Government had in mind.

Incorruptible Independence

By this time he had a press of his own, and a book-shop. But Gundappa was not cast in the mould for strict business. The press and the the book-shop, therefore, were only partly successful.

Fifteen years of hard and selfless service had, however, made Gundappa into a man of grit and incorruptible independence. Dewan Mirza Ismail recognised this when he assumed office and sought his cooperation. Gundappa did cooperate. But this cooperation too was short-lived.

The disturbances in Bangalore city resulting from an unwise act on the part of the Dewan put Gundappa on the side opposed to the Dewan. In one sense, perhaps, this was a blessing. The incorruptible man was left safe in his incorruptible position.

But Gundappa’s position as the leader of the people was now so high that he could not be ignored. He became a member of the City Municipal Council, of the Legislative Council, and the University Senate. Otherwise also he took part in large national activities like the Indian States Conference which sought to make the Rajas and Nawabs share their power with their people. In work in this connection Gundappa stood with Sir M Visvesvaraya and other stalwarts from all over the country.

All this time Gundappa had been writing in Kannada. He was among the people who worked to bring into existence in 1915 the Kannada Sahitya Parishat (the Kannada literary academy). He was helpful in the work of the Karnataka Sangha of the Central College which pioneered literary production and research. Gundappa’s earliest significant works in Kannada were the life of “Dewan Rangacharlu” and “Vasanta Kusumanjali”, a collection of poetical pieces published by the Karnataka Sangha of the Central College, Bangalore.

With V. S. S. Sastri

Some years later it happened that Sri V. S. Srinivasa Sastri toured the State as a guest of the Government and visited a number of interesting places. He solicited Gundappa’s company. Gundappa went with him to all these places and, exhilarated by the experience, wrote some beautiful Kannada verse which he published (1924) with the title “Nivedana”. In these years Gundappa did also a good deal of miscellaneous high-class writing in Kannada and was chosen President of the annual literary conference of 1932 held in Mercara.

His position as writer was high enough by 1933 to make the members of the Kannada Sahitya Parishat elect him the executive head of the institution. The institution had worked for some eighteen years as a scholars’ institution without coming into contact with the people. Gundappa took it out of the rut and arranged to hold courses of training for teachers in Primary and Secondary schools, so as to put them in touch with modern literature and science, and organised a festival each spring with programmes of lectures, competition and dramatic shows.

When he ceased to be the Vice-president in 1937, the Parishat was an entirely different type of institution engaged in active work for the spread of knowledge among the people.

In 1932, Gundappa and a few journalist friends started the Mysore Journalists’ Association. Gundappa was the first President.

The Gokhale Institute

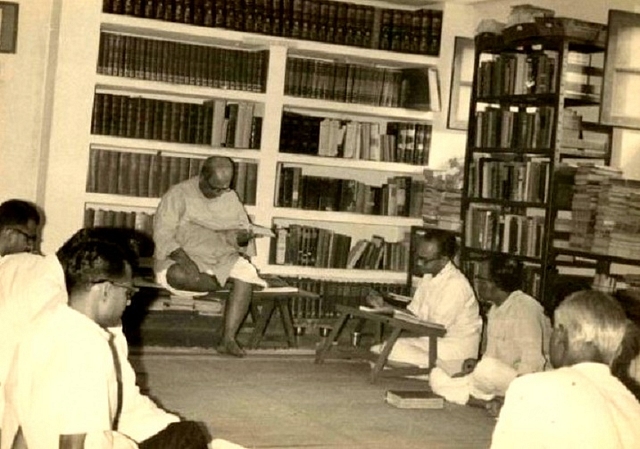

After thirty years of miscellaneous activity, Gundappa left the need for an institution where he could work continuously for raising the level of knowledge among our people in all branches of public life. The Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs founded in 1915 had not stopped working but had no substantial achievement to its credit. Gundappa now began work to make it a real centre of study and research and propaganda. He found no widespread support for these ideas, but some number of people who realised what an asset he was to public life, stood by him, Gundappa used even this exiguous support to such good purpose, that he could raise enough money for having a building for the Institute in the part of the City now known as the Narasimharaja Colony. The Institute celebrated its Jubilee in 1965, and the celebration was a grand function with His Highness Sri Jayachamaraja Wadeyar presiding and Smt. M. S. Subbulakshmi entertaining the gathering with her superb music. It is now an institution of high standing with a number of lecture courses instituted by cultured persons. One of the courses is in honour of Rajaji and has been instituted byn Sri T. Sadasivam and his wife, Smt. Subbulakshmi.

Gundappa has done much miscellaneous writing in English both as journalist and publicist. In the last few years he edited the Bulletin of the Gokhale Institute. His writing in English, as in Kannada, was classical in quality.

Proficiency in Kannada and English

Gundappa had to do a great deal of public speaking in the course of his work. He spoke well both in Kannada and English. On the topic on which he could speak with authority, he could address an audience for an hour or more at a time, holding the attention of the hearers throughout.

Gundappa, in the early years, advocated unification of the Kannada areas of the country but later changed his mind. The movement, however, had gathered sufficient force to proceed further in spite of objection from some quarters, and the State of Karnataka came into existence nineteen years ago.

Though a writer of distinction in Kannada, and a worker for the progress of the language, Gundappa thought that English should continue in its present position for some time longer.

A Non-Party Politician

Gundappa never looked for appreciation of the work he was doing, by the Government. He was a politician but belonged to no party. If he had joined the Congress in the earlier years, he could perhaps have been a minister in one of the administrations later. In literature also he was indifferent to acceptance by the crowd, though maintaining high quality. So, in spite of indifference to name and acceptance, he was honoured and the degree of Doctor of Letters by the Mysore University in 1961, an award for the best work in Kannada from the Central Sahitya Akademi in 1967, and the distinction of Padma Bhushan by the Union Government in 1974. About a year ago he was offered a pension of Rs 500 a month by the Government of the State. He declined it.

One wishes that this last offer had been made some twenty years earlier. A pension then, with years of work in front might have been acceptable, as helping to enable him to concentrate on the work without troubling about resource. Even now he could have received the pension, and turned the amount over to the Institute he had established. But that was not the way the man was made.

Friends celebrated Gundappa’s eightieth birthday in 1970 and presented him with a purse of about a hundred thousand. Gundappa, with characteristic indifference to possession, turned the whole of the amount given to him over to the Institute.

The Institute is now a fitting memorial to the great public work done by this servant of the people.

An Excellent Conversationalist

Gundappa’s personal life was clean and simple. His relations within the family and with people outside were almost exemplary. He was an excellent son, a good brother, and a good father and uncle. He lost his wife when he was about thirty-sex years old, but would not re-marry. There was a widowed sister in the house. When his parents pressed him to re-marry, he asked them why they did not think of re-marrying the daughter. That stopped any repetition of the proposal.

A man of deep personal affections, and highly emotional, he kept himself in hand by strong good sense. He was a loving friend and was loved by all who worked with him. He was an excellent conversationalist and was a jovial member of any company which he chose to join. He had a keen sense of humour, and could make a joke and take a joke. Sometimes he composed humorous verse. On one occasion that I remember, this was in Telugu.

The humour was somewhat broad, but suited the atmosphere. Gundappa loved Karnatak classical music. He composed some beautiful songs in Kannada to be sung in Karnatak tunes. The first song he composed is used as the prayer song in meetings in many Karnatak Sanghas in this part of the State.

Born poor, receiving no formal education beyond the secondary stage, and entering public life when he was about twenty years old, Gundappa worked hard and with a will to make something of life; and ended making it a great thing. He read and thought; read widely, thought carefully.

He wrote and spoke; wrote thoughtfully, spoke carefully. He worked in many fields with no eye to profit for himself; and always with the idea of doing good to the public which he was serving. In the sense of good work for its own sake, he succeeded in every field in which he laboured.

A Gift of the Kolar District

With no advantage of birth, or wealth or office, he attained a position in the life of the State that few with all such advantages ever did. People now utter his name as equal inimportance to the name of Sir M Visvesvaraya as gifts of the Kolar district to the State, and those who hear them feel that it is quite proper.

Gundappa was a man of strong will. The last few years were a time of very poor health for him; but no one saw any fall in the quality or quantity of the work that he did. The illness never affected the quality.

His interest in the welfare of the people was as intense in his very last days as ever before. Only a few weeks before the end, he thought of two committees which could examine two important questions; and wrote to me among others, asking me to be a member.

Gundappa was altogether a rare type of man. The world at large may not know him as such, but he was a great man.