Checks And Balances In The Indian Constitution: Poorly Conceived, Reviewed And Now In Disarray

Governments will take their responsibilities lightly with poorly defined checks, which is not befitting a great nation.

The primary aim of any nation’s Constitution is to establish a responsible government. This is usually done by creating independent institutions of governance, assigning them well-defined duties, giving them specific powers, and making them answerable to the people. Accountability is ensured through periodic elections and internal checks and balances. In our Constitution, though, these checks and balances were poorly conceived from the beginning. And their so-called improvements have only made matters worse.

Legislative Oversight

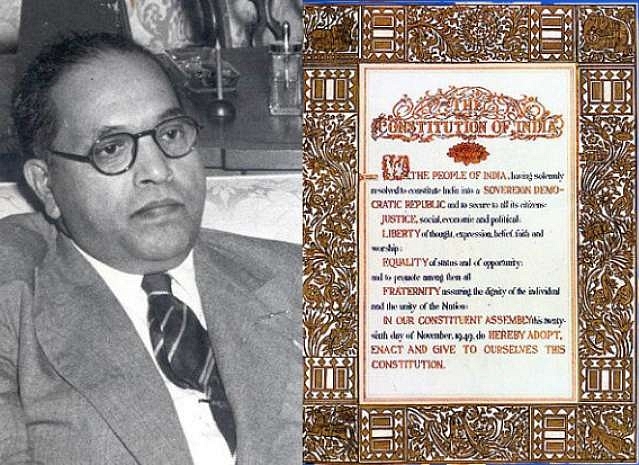

Consider the most fundamental check, the legislature’s control over government. B R Ambedkar touted this as one of our Constitution’s greatest strengths. In his famous ‘responsibility versus stability’ speech in the Constituent Assembly, he noted that “a parliamentary government must resign the moment it loses the confidence of a majority of members of Parliament.” Thus our governments may be less stable but they were more responsible. “The assessment of responsibility of the executive is both daily and periodic,” Ambedkar said. “The daily assessment is done by members of Parliament, through questions, resolutions, no-confidence motions, adjournment motions and debates... periodic assessment is done by the electorate at the time of the election.”

It is easy to see the impracticality of this type of legislative scrutiny of government. MPs are expected to assess the overall performance of government on a daily basis. And if a government is found to be irresponsible, MPs are presumed to be willing and able to act immediately to oust it from office. Not only that, a majority of MPs are expected to end their own terms in Parliament, for this is what ‘bringing a government down’ typically means.

And so only one government in our history has ever been voted out of office, that of V P Singh in 1990. Many governments fell before term, but it was always due to MPs changing political parties or party bosses shifting their alliances. Thus instability in Indian governments became a huge problem.

The attempted fix for this ailment, the anti-defection laws of the 1980s, made the situation with legislative oversight even worse. Now MPs cannot vote against their party’s wishes on anything at all, what to say of no-confidence motions. No matter how irresponsible, a government is now guaranteed majority support in Parliament. As for the daily assessment of governments’ behaviour, MP Shashi Tharoor said it best in 2017: “The notion that our system provides a ‘daily assessment of responsibility’ would be laughable — given the performance of the last Parliament with all its disruptions and adjournments.”

Presidential Control

Similar is the story of presidential control over Indian government. The Constitution placed our President at the head of the government, but failed to specify what powers his office really held. An Instrument of Instructions detailing presidential powers was promised in the Constituent Assembly but was never added to the Constitution.

India’s first President, Dr Rajendra Prasad, fought with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru for a decade to determine the exact nature of his powers. A constitutional crisis was averted within the first year, when Nehru threatened to resign over this rift. In 1957, Dr Prasad made the issue public, arguing that the Constitution gave the President the power to overrule a Prime Minister’s advice. Dr Prasad’s view found some support in 1963, when K M Munshi, a senior member of India’s Constituent Assembly, wrote a book describing how the founders didn’t intend a figurehead President.

Any hope of the President keeping a government in check however was dashed in 1976, when Indira Gandhi’s 42nd Amendment rendered the office completely impotent. Article 74 of the Constitution was changed, stipulating that the President “shall act” in accordance with the Prime Minister’s advice. The Janata government that followed did nothing to repeal this appalling provision. It only gave the President the right to ask the Prime Minister for reconsideration, after which he must do as told.

This perversion of the original Constitution still stands. Nani Palkhivala, noted constitutional scholar, wrote that Indira Gandhi’s amendment “destroyed the basic structure of the Constitution.” Similarly, Granville Austin, famous chronicler of the Constitution, noted that “the shift in the balance of power within the new Constitution made it all but unrecognisable.”

As a result, an Indian President’s situation today is ridiculous. The President is the creator of the Council of Ministers with a Prime Minister as its head to “aid and advise,” but he must act according to that advice. So, what’s the difference between ‘advice’ and ‘order’? This system has made an appointing authority subservient to its subordinates. Similarly, the Constitution vests all executive powers and command of the military in the President, but then requires him to do as told by the Prime Minister. So, who’s in command of the government or the military? The logic is absurd.

Judicial Review

The judiciary has fared slightly better in keeping Indian governments in check, but no thanks to the Constitution. The original Constitution gave a government a free hand in changing the document itself, or in appointing judges of its own choosing.

In the early years, the Supreme Court held twice, in Sankari Prasad (1951) and Sajjan Singh (1965), that there were no restrictions in amending powers of Parliament. As a result, all official reviews of the Constitution – First Amendment (1951), Fourth Amendment (1954), and Forty Second Amendment (1976) – were ways governments found to get around the original Constitution. It was only in the 1973 Kesavananda case that the court began to enforce the doctrine of basic structure, limiting the powers of government.

But the court had presumed primacy. The Constitution doesn’t describe any features as “basic”. Today, the court reaffirms the doctrine of basic structure and defines it at will. Justices include every personal preference as “basic” to the Constitution: a welfare state; equality of status and opportunity; an egalitarian society; balance between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles; socialism, secularism, and so on. Justice Chandrachud has gone so far as to make the absurd statement that “the theory of basic structure has to be considered in each individual case…”

As for limiting the power of government over appointment of judges, in 1993 the court presumed that role as well. But now India has a system of judges appointing judges behind a veil of secrecy. There is no public scrutiny of their appointment or their performance.

Indian governments can never be responsible with such poorly defined checks. It’s not befitting a great nation.