Dealing With Vacancies And Jobs: Solution Is To Shrink The Govt, Not Expand It

Two million posts lie vacant at the centre and in states. We need to ask two questions here:

- Do we really need to fill these posts and expand the already bloated bureaucracy?

- Does our system reward deserving candidates given our reservation system and rampant corruption?

If the answer is no, filling these posts may do us more harm than good in the long run.

Critics are still

debating whether Modinomics is about big projects like Make In India, Digital

India, Skills India, Startup India, Smart Cities or about fixing small but important things like building toilets for girls in schools, Swachh Bharat, doing away with the attestation of documents by gazetted officer, and fixing the NPA mess left behind by the UPA.

There is no reason why both can’t go hand in hand.

However, administrative and judicial reforms are conspicuously missing from this government’s agenda. To be fair, the government’s attempt to bring more accountability to judicial appointments was scuttled by the judiciary.

Problems are plenty and daunting. Shankkar Aiyar’s eye-opening column in The New Indian Express succinctly reveals the rot in administration today, both at the state and centre level.

Every year, 12 million (1.2 crore) people enter the job market in India. Make in India and Skill India are long term projects which will start bearing fruit probably in Mr Modi’s second term - if he wins in 2019. So, is there a short-term remedy? Perhaps, the solution lies in the challenges itself.

Consider these numbers put out by Aiyar:

#1 The total number of vacancies across ministries in Central government are 6,02,335.

#2 Nearly 2.25 lakh posts are lying vacant in the Railways alone, out of which 1.24 lakh posts are related to safety functions.

#3 65,739 posts are lying vacant in Central Armed Police Forces.

# 4 The total number of sanctioned but vacant posts in state police departments are 5, 42,986. Uttar Pradesh alone has 199,160 vacant posts.

#5 37 percent of our schools have an adverse teacher-pupil ratio. There are 514,784 vacant teacher posts across India.

#6 101 posts of functional directors and around 440 positions of non-official directors are presently vacant in various Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs).

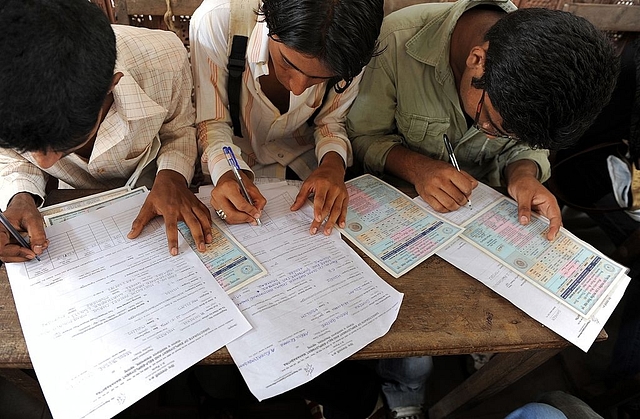

All in all, around two million government posts lie vacant at the centre and in states. Shouldn’t the government then, the argument goes, focus first on filling these vacancies rather than putting its proverbial eggs in the distant success of Make in India/Skill India basket?

There are two issues here we need to consider while dealing with government jobs.

First, we need to ask ourselves, do we really need to fill these posts and expand the already bloated bureaucracy? In the era of minimum government, it doesn’t seem prudent and certainly not when the future of jobs look bleak. As R Jagannathan writes in this Swarajya column:

When most normal functions can be automated or digitised, employing a whole army of office-bound babus and employees may be counter-productive.

The government is giving up its control—however slowly—in PSUs and is disinvesting its share. In a decade or so, the government should aim to hold onto only assets of strategic value and keep getting out of loss-making public enterprises. Bonus: It won’t have to bother about filling vacant posts.

Teacher-pupil ratio is often touted as an issue that needs to be dealt promptly. Half-a-million teacher posts are lying vacant. Here, the critics need to stop for a moment and think it through. Remember, we have many public schools where there are teachers but no students to teach. This number is increasing. Parents, even poor ones, don’t want to send their kids to sarkari schools.

So, why can’t we move from funding schools to funding poor students? Let students from poor families pay fees in private schools, which are better than government-run schools, via vouchers funded by the State. Don’t mind the five-star activists who would never send their own children to a public school. So, filling vacant teacher posts may exacerbate the already worse situation instead of solving it.

Of course, the government must move fast in filling vacancies in indispensable areas such as Armed forces and police.

Second is, of course, the issue of availability of worthy candidates for the vacant posts, which Aiyar also notes. One is not saying there aren’t eligible candidates but many of those deserving candidates may not even get the job. Out of two million posts, more than one million are already reserved.

States like Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have exceeded the fifty percent quota limit mandated by the Supreme Court. Others may follow suit, especially Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, where influential Marathas and Kapus have staked claims for a share of the quota pie.

Of course, most of the people who come through quota may be talented and well-deserving but reserving half of the available seats certainly limits the opportunities for talented students who do not belong to the backward classes.

Then there is the issue of rampant corruption, especially in states where people with connections to the politico-bureaucratic nexus are most likely to get those vacant government jobs than the deserving ones. Then, should we even hope that these posts get filled?

Certainly not. Not until we have a transparent system in place or a better and rationalised quota regime.

The exigencies of joblessness demand quick action from the government but if it goes on filling these vacancies without fixing the aforementioned issues, it may do us more harm than good in the long run.

The solution lies in shrinking the size of the government and making it smart, not expanding it.