In Numbers: Here’s What Is Needed To Come Up With A Comprehensive Response To Covid-19 At Taluk Level

How local administrative units in India can come up with the infrastructure to test and treat Covid-19 patients.

For many of us, the COVID scenario unfolding is not unlike what is depicted in the play, Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett.

Like the protagonists, we have a lot of time and our minds are racing ahead with possibilities, expectations, even analysing multiple scenarios and mathematical curves.

The participants in the novel do not seem to do any extraordinary things; they do the mundane stuff – wake up, spend time in finding food, argue, get tired, find food, argue more till they are tired again — not very different from how our current routine looks.

They wait for Godot, who never arrives. But the metaphor of the novel or the core idea is a powerful one — it seeks to define the meaning of life and showcases the shallowness of our approaches to it.

You can ignore the ramblings, but when I was contemplating on the consensus among the media and the elite that India as a poor country cannot manage this public health crisis due to our poor healthcare infrastructure, lack of knowledge and the overwhelming numbers, it seems to me that we are being led to be like the participants of the play, waiting for something to happen.

But, India is way beyond these conventional ideas and we have demonstrated it many times to ourselves and to the rest of the world. I always believe that India’s strength is in numbers.

A parallel idea occurred to me to leverage the same to manage the COVID crisis and I would like to expand it below.

As I understand from the readings and the media,

· 80 per cent of those who are infected by COVID-19 will manage without hospitalisation, if they follow simple procedures.

· 15 per cent of those who are infected will need medical care including hospitalisation.

· 5 per cent will require critical care, led by medical professionals and ventilators, etc.

But this fact is often overlooked in the common understanding that exists among normal citizens. Everyone is linking the occurrence of the infection to mortality and fear rules the actions.

In a way, it is good because it helps the majority adhere or try to follow the guidelines from the government. But if we account for the panic and look for solutions in managing the crisis, we need the following elements in place, well before the pandemic spreads in the community:

1. An accessible location in the community where the ‘testing’ and ‘treatment’ can begin for 80 per cent of the infected citizens.

2. A medical facility to identify and treat the 15 per cent of the seriously infected, where we need trained medical professionals.

3. A specialised hospital to take care of the critical cases, with ventilators etc.

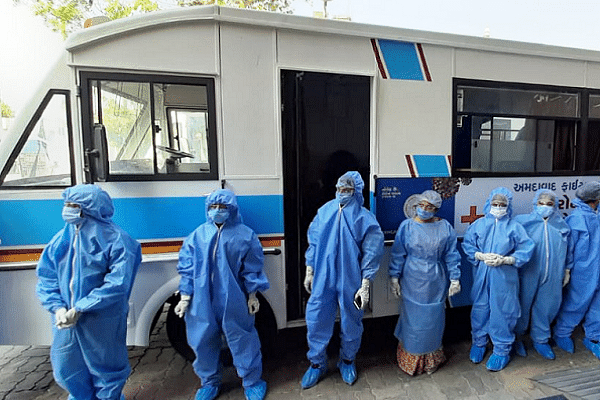

4. A logistics solution to move medicines, PPEs and even healthcare professionals.

The last two cases would require medical professionals and equipment.

Let’s translate these into actual numbers at a mandal/taluk level in the Indian context. (All these numbers are taken from the published sources and this estimation relies on averages. The accuracy will improve when actual data is substituted at a granular level).

Total population of India – 1,300 million

Total no of mandals/taluks – 5,650

Average population per taluk – 230,888

Testing: Assuming we need to test 100 per cent of the population in a taluk.

If the test takes an hour to complete, then the daily average is about 10 people per COVID centre.

If there are 183 COVID centres (I will come to this number in a minute), then the number of days to complete testing will be as follows:

Number of people per COVID centre : 1,256 (230,888/183)

Number of days to cover

10 per cent of population — 13 days

50 per cent of population — 63 days

100 per cent of population — 126 days

This means in about 100 days, we can actually complete the testing. The testing kits are another story, but it is a question of finance. Also, no one has recommended 100 per cent testing.

Indian Council of Medial Research (ICMR) has said that 80 per cent patients will only have mild fever and cold before being cured. And they won't even realise whether they were positive or negative.

Please note that the healthcare personnel involved in this category can be effective, with good training and SOPs with very less ‘time intervention’ from doctors.

The government has already mobilised voluntary teams for monitoring and observation.

Now, let us assume a worst-case scenario of infection rate at 10 per cent (Pray to god that it is not the case).

Again, at a mandal level, this translates into:

Number of people in the 80 per cent category: 18,407

Number of people in the 15 per cent category: 3,451

Number of people in the 5 per cent category: 1,150

Remember that we said we need medical professionals for the last two categories.

Let’s look at the broad numbers again.

Total no of healthcare professionals in India: 2.2 million

This translates into:

Average number of healthcare professionals per mandal – 389

If all of them are mobilised to focus on COVID at the COVID centres, then the average number of patients they need to work on is 12 {(3,451+1,150)/389}, which is not a very unmanageable number.

Please also recollect that all the patient arrivals will follow some mathematical distribution with intervals.

More importantly, we need an average of 25 beds in each of the 183 centres {(3,451+1,150)/183} and we will see how that can be made available.

Now, consider the actual accomplishment of India 12 months ago. If we turn the clock back one year, last April, the Election Commission of India managed this scale, of course, for a different reason.

In 38 days, 1.035 million polling booths covered the nook and corner of India.

· 2 — The maximum distance in kilometres from any given voter’s house to the nearest polling booth

· 3.96 million: Number of electronic voting machines (EVMs) in use this election

· 1.7 million: Paper trail or voter-verifiable paper audit trail machines.

· 11 million: Election personnel being deployed to conduct polls

· Election commission has the SOP for mobilising district administration, police and even paramilitary forces.

All of us can now see where the 183 number is coming from. Yes, that is the average number of polling booths per mandal. So, we need a plan that will convert each polling booth into a COVID centre/booth.

Also consider this:

Number of schools in India — 1.6 million

Number of polling booths — 1.035 million

So, it is not a coincidence that you almost always encounter a school near your home as a polling booth. It is by design. And that is where we can get our 25 bed “hospitals”.

So, we need a 100-day plan for India to effectively combat the deadly virus.

· Replace polling booths with schools

· Replace EVMs with medicines and equipment.

· Replace Election SOPs (quite complicated) with COVID SOPs (fairly simple for the 80 per cent)

· Replace high-risk polling booth strategy with COVID high-risk strategy (to address personnel, additional equipment)

· Replace counting mechanism data dissemination with COVID data to ensure that the entire nation gets to know the real-time-data on the progress of treatments.

· Replace candidates with COVID volunteers including the same political candidates to ensure the information dissemination happens to every citizen (voter).

· Replace polling booth agents with corporation/panchayat staff and government volunteers (the volunteers are already doing a good job in conducting door-to-door surveys)

I am not suggesting all 1.6 million schools need to be involved. Schools which fit the criteria in terms of space, hygiene et cetera will be co-opted, whether private or government, for the hospital model.

Once the experts define the basic specifications, the local government machinery will keep adding the missing infrastructure to manage the gaps.

For example, high schools can be ‘hospitals’ and middle and elementary schools can be ‘isolation wards’.

It is important to look at each mandal and decide as per the locally available infrastructure.

You can co-opt marriage halls, warehouses too (this is from my personal experience of looking for space in villages for DesiCrew/GramIT centres).

Medical waste handling et cetera will have to be managed by protocols evolved by medicos — like we have for infectious diseases like TB.

For handling the 5 per cent critical patients, the network of existing hospitals (again both government and private) and the ad-hoc arrangements can be made (we still have time).

The Railways have already done excellent work in this regard and I understand that the Chennai Trade Centre, which regularly houses international expos, is now a 1000-bed hospital (I saw a picture in a national newspaper of a mall being converted into a food distribution centre with rows of migrants sitting on swanky floors with escalator at the backdrop, places they normally would not be entertained).

And finally, non-COVID patients also need attention. In-patients will continue in the hospitals, and this will create a shortage of medical professionals.

This is the biggest challenge we face, in my view, but it can be also addressed by roping in entire medical college graduates (may be third year onwards) with good training and virtual live sessions from the experts.

The good part about COVID (if you can call it that way) is that the treatment is largely ‘supportive’ not ‘curative’ and hence more emphasis is on following SOP with some good zoom calls (Remember the climax scene of ‘3 Idiots’ in delivering a new baby).

Co-morbidity cases are different and it is a complex issue because in our current system also, not all hospitals can take care of clinical emergencies.

But health practitioners may have already thought of a solution for that issue too.

Of course, the challenges of ventilators and forming medical teams need to be addressed. But given the power of India’s inherent beliefs among the citizens, this can be done, with a lot of careful planning.

The Election Commission usually takes about 365 days for preparation, but that includes electoral rolls, etc, but now, we can re-use most of the data, which is just a year old. Hence, a 100 days of solitude should be possible for the country.