India Carried The White Man’s Burden Through The Great War – And That Must Not Be Forgotten

It was on Indian shoulders that the modern world was forged, and this is a claim that we now need to underscore and emphasise to the West.

Take up the White Man’s burden

Send forth the best ye breed

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

– Rudyard Kipling

In 1917, with the First World War having reached a crescendo, a young history student from Rawalpindi at Balliol College, Oxford, offered to join the British Indian army as it was locked in a death battle in the trenches of Europe against the Germans. His offer, however, was of a nature that made the British gentleman officers choke on their Devonshire tea and scones – the 21-year-old Indian wanted to join not as an enlisted man, like all other Indians did, but instead wanted to fly as a pilot with the Royal Flying Corps, the predecessor of the Royal Air Force.

In 1917, airplanes were new, military airplanes newer still. They represented the pinnacle of the white man’s achievement, the triumph of Renaissance values of science and rationality over the decadent mystic-metaphysical cosmology of oriental civilisation.

To entrust an Indian with such a responsibility was unthinkable when merely a decade and a half ago, Kipling had exhorted in his anthemic poem the need for the white man to take upon himself the burden of civilising the “savages”. There was further the problem of rank – pilots in the air force could only be commissioned officers and, in 1917, it was likelier that the English invite the Germans over for afternoon tea than an Indian be made an officer at par with the white man.

Instead, the young Indian from Rawalpindi by the name of Harditt Singh Malik was assigned the role of an ambulance driver.

A short train ride away from Oxford in Kensington, P L Roy, an eminent barrister in London, and his wife, Lolita Roy, proudly watched their 17-year-old son, Indra Lal Roy, grow up into a fine young man playing rugby and cricket at an elite English school. The family had moved to London from Calcutta in 1901.

When the Great War broke out, Indra Lal Roy knew what he wanted above all – to fly a plane. However, despite having studied in the best English schools where he captained his school swimming team, Indra Lal Roy was still a brown boy in a white man’s war.

Back in Oxford, Harditt Singh Malik took up service with the French Red Cross, where his abilities were valued for what they were and the French readily agreed to commission him as a fighter pilot. The ignominy of a British subject fighting for the French, however, finally pierced the colonial hide and induced embarrassment among the Lords and the Barons.

Upon a letter of recommendation written by Malik’s professor at Oxford, a temporary, yet historic exception to the rules of service was made – Harditt Singh Malik would be given a temporary commission as an honorary Second Lieutenant to enable him to fly fighter aircraft with the Royal Flying Corps.

This was the moment that Indra Lal Roy in London, too, had been waiting for, all his life. By July 1917, he had cleared the stringent eligibility requirements – made doubly strict for Indians – to qualify as a fighter pilot.

Within a few months, two more Indians joined the ranks. One was Errol Chunder Sen, a nephew of the Maharani of Cooch Behar, who herself was the daughter of the Brahmo Samaj reformer Keshub Chandra Sen, and the second was Sri Krishna Welingkar from Bombay, distantly related to the erstwhile Maratha royals.

The life expectancy of a fighter pilot in the First World War was only 10 days. These machines that carried men in the air were crude contraptions compared to even the simplest of airplanes of today. Each one of these young men would have been only too aware of this fact. Despite that, they distinguished themselves. Indra Lal Roy was the first Indian pilot to be recognised as a Flying Ace – he destroyed five enemy aircraft in under 170 hours of flying.

At the age of 19, and after one year of doing what he loved the most in life, Lieutenant Roy was shot down by a German plane. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously. Lieutenant Sri Krishna Welingkar would not survive the war either. Errol Chunder Sen was captured by the Germans and spent the rest of the war in a German prison. Only Harditt Singh Malik managed to get through the rest of the war in a plane.

Today, their actions may not evoke much emotion in us. But in 1917, the heroism of these men was nothing short of a minor revolution. Within one year, the doors of entry to the commissioned ranks of the British army were opened to Indians, much to the distaste of, and in the face of stiff resistance from, defenders of the Raj.

Following Kipling’s legacy, the colonial state viewed itself as benign and altruistic – carrying the onerous burden of governing India since the natives were deemed incapable of doing so. Each time Indians proved this wrong was a reclamation of the nation from the empire. The fight of Malik, Roy, Sen, and Welingkar to be treated on a par with British pilots was one such battle that helped reclaim the nation from colonialism, albeit one that we have deliberately chosen to forget.

And it wasn’t just about India. The myth of the invincibility of the white man was shattered forever when, in front of the cornucopia of human races that colonialism had assembled in the trenches of Europe, the flesh of the white man yielded like paper to the bullets and bayonets of Indians. The spectacle was there for all to witness when the African and the Malayan went back to their villages.

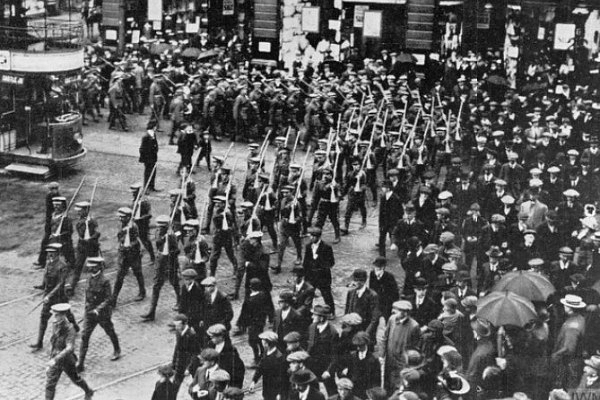

By 1918, more than one million Indians had fought in the First World War. Some 74,000 Indians fell to enemy bullets and lie buried in graves as far away as Ypres, Flanders, and Mesopotamia. At some places, memorials mark their sacrifices. At others, nothing remains.

The Politics of Remembrance

It is unfortunate that due to the exigencies of post-Independence politics, exemplified by red herrings such as the Non-Aligned Movement and a misguided pacifism, the Indian nation chose to disown the sacrifice of its soldiers who went to fight for the Raj.

For the newly independent nation, the question of who and what is worth remembering from its chequered past was critical. There is a line of reasoning that asserts that the British Indian army, as a tool of conquest, should not make the cut in the pantheon of remembrance.

Most recently, this logic was encountered when objections were raised to the renaming of Teen Murti Chowk in New Delhi as Haifa Chowk in honour of the Indian troops who liberated Haifa from the Ottomans. Ironically, it is also the proponents of this same line of reasoning who forcefully assert that the Indian nation and nationalism are a creation of the British Raj, in particular, the British Indian Army.

Were we to go about purging the British Indian Army from our national memories based on these grounds, we would also need to erase all remembrance of the millions of Indians who worked for the colonial state – as scribes, clerks, civil servants, barristers – and upheld the illegal occupation of the land. Even our political leadership, from Mahatma Gandhi to Jawaharlal Nehru to Vallabhbhai Patel to Subhas Chandra Bose, worked for the colonial state as barristers or officers at some points in their careers.

Why should the soldier, then, be singled out for erasure from memory? Nor was the Indian army the only medium through which colonialism spread. The Indian railways was, perhaps, an even more powerful medium. The laying down of railway tracks enabled connectivity from Burma to Bannu and from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, thus enabling easy subjugation of the perennially rebellious Indians.

The British even took Indian workers abroad to Africa, Guyana, and Malaya to help build the railways and expand their empire. It would be foolish to declaim that since the Indian railways was a tool of colonialism, hence its legacy must be denounced as one of oppression.

A remembrance of Indians dying in the service of the British empire, then, is not a validation of the empire. It is a celebration of the valour and martial traditions of India.

Carrying the White Man’s Burden

Absolute truths are rare in the world we live in, and even less so in war. The two World Wars are, perhaps, an exception. In a war fought between colonisers and exploiters for the control of the world’s manpower resources, we are in near-unanimous agreement about which of the two sides presented the lesser evil, a global consensus that has stood the test of time and persisted down to our day.

This is a rarity in a postmodern world where nothing is ever certain and there exists an equally convincing counter-narrative to every truth. We know for certain that not only was India on the right side in the two wars, but that India was also among the largest contributors of men and material. It was on Indian shoulders that the modern world was forged, and this is a claim that we now need to underscore and emphasise to the West. India didn’t just show up; India decided the fate of the war.

As India rises among the ranks of the great powers, it is important that we leverage this sacrifice of our men to remind the West of this debt. We need to do this through the medium of literature, academia, and, above all, cinema – for it has the widest appeal. An entire generation of Indians today can recount names and places such as Normandy, Flanders, Ypres, and Dunkirk, thanks to Steven Spielberg, Christopher Nolan, and Stanley Kubrick.

But who will tell the story of 19-year-old Indra Lal Roy who went down in a blaze of glory as a World War Flying Ace? Or that of Errol Chunder Sen, the Maharani’s nephew who crashed behind enemy lines and spent the war as a German Prisoner of War?

It is a rhetorical question, of course. We will have to tell those stories. To ourselves first, and then to the world. We carried the white man’s burden through the war. It is time now to remind them of it. A 100 years after the end of the First World War, Kipling seems relevant again, albeit in irony.