Krishna Gopeshvara - The Avatar Versus The Prophet

‘Krishna Gopeshvara’ is an important literary attempt to look at the life of Sri Krishna as told in Bhagavata, and which reflects the present problems faced by the Hindus.

It is often said that Hindus do not have a sense of history. Instead, they have puranas. Puranas are usually translated as mythologies and mythologies in turn are understood, at least in the general psyche, as just fiction – at best with a small historical core many zillion times exaggerated. A Hindu instinctively knows that her puranas are more than glorified fictions with a historical core. They belong to the realm of meta-history. They happened and they happen and they will happen again – not just in external cyclical time, but also in the inner psychological realm. They are both history and archetypes. From the puranas, India has perennially created poetry, sculpture, psychological disciplines, sociological understanding etc. However, with the advent of colonialism this flow seemed to have stopped.

The divide between mythology and history was imposed on our puranic discourses. Let us find the ‘historical Krishna’. What are the archaeological correlates of Mahabharatha and Ramayana? Is Ramayana a mythologised version of an Aryan intrusion into the Dravidian south? Are the vanaras actually tribal clans? Such probes tend to refashion our Puranas into the frame of knowledge of colonialism. After Independence the same ethnic reinterpretation of the Puranas continues to dominate our literary and academic landscape. In addition, Marxist reinterpretation of the Puranic discourse further pushed the reductionist agenda. So is Ramayana is actually agricultural expansion drive of the Indo-European clans? Can Mahabharata be explained through dialectical materialism and production relations that exist in the society? D D Kosambi created a Marxist framework for looking at our epics and Puranas. Already Marxist scholar Rahul Sanghrityayan had written a literary propaganda piece on the supposed evolution of the Indian society. Many people even quote from this propaganda piece as if it were real history.

This detailed context needs to be told to understand Sanjay Dixit’s book ‘Krishna Gopeshvara’ – the Book-I of the ‘Lord Krishna Trilogy’.

The book is an important literary attempt to look at the life of Sri Krishna as told in Bhagavata from the perspective of the clash of religions as is happening in India right now. So Kamsa, the maternal uncle of Krishna, is transformed into a veritable Constantine running an inquisition for Kutil Muni who in turn is an expansionist predatory cultist. His religion is based on intolerant premises – no image worship, destruction of temples, apocalypse, last day, final judgment, eternal hell - not for bad behaviour but for disbelief in the cult and so on. He spreads his cult through the monarch Kamsa. ‘One God, One Book, One King’ is surely a great way to control people, and every dictator of pre-monotheist society would love to have such a weapon handed over to him. Kamsa is no exception and there is one danger to this great plan to make entire ‘Aryavarta’ fall into submission unto the one god (and hence one emperor and his dynasty). A lovable dark hued cowherd among a pastoral community poses a threat. The novel in the form of a narration goes through the different deeds of Krishna – removing the supernatural elements and substituting them with natural explanations.

This first literary attempt by the author is in a way looking at the present existential problems faced by Hindus through the ancient history of Krishna. One example: the way Kutil Muni tries to use the Arya-Naga divide to convert the Nagas shows how the author sees through the Bhagavata – the present day challenge the dharmic society faces – particularly when evangelising religions use the social fault lines to further their agenda. The Nagas when at last faced with the rapine predatory Kutil dharma, realise that they have more in common with the so-called Arya dharma than with the expansionist monocultural Kutil dharma. The more than 300 pages novel is filled with such parallels.

And the way the character of Radha is developed in this novel is interesting. Radha is never named in Bhagavata. She emerges later. Her identity is in a way mysterious. Here she represents something unique in Hindu tradition - the authority that the feminine has over spirituality in our culture and society. One is reminded of the continuity that flows through from vedic women seers to Brahmani who instructed Sri Ramakrishna in tantric practices.

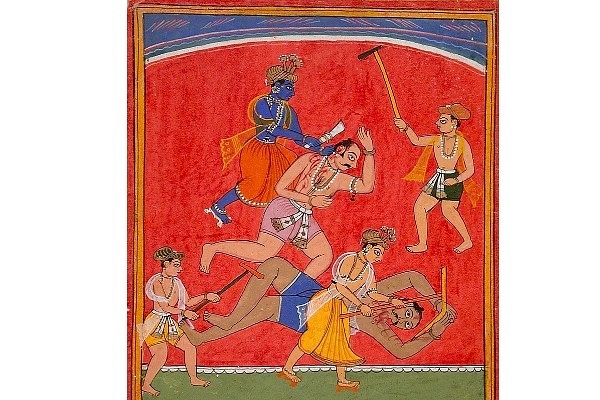

Kutil dharma – the expansionist monotheist cult becomes as much an important thread throughout the narrative as Sri Krishna is. The twisted Swastika, the symbol of this cult, is shown along with the face of Krishna in the cover illustration. Particularly when, Kamsa who uses the cult to further his own fame, decides to proclaim himself as the only begotten son of Jhankal the god of Kutil dharma. This is what Elaine Pagels, the authoritative scholar on early Christianity, calls ‘the politics of monotheism’. Against this ‘only-begotten-son’ or ‘the-only-prophet’ syndrome, Krishna’s emergence as avatar is differentiated. Krishna never goes around claiming himself to be an avatar and he does not demand faith from his friends in his avatar. Acharya Chandrakaushika, through whom the deeds of Krishna are narrated, explains this concept of avatar to Jarachanda. The Prophet-based-god cult is imposed from above; it demands followers. The nature of Krishna’s avatar simply flowers through his deeds and is recognised through love and friendship. Sanjay Dixit has successfully brought this out.

Again, one should remember that this is also a reinterpretation of Krishna and Bhagavata. Here, Sri Krishna is not a deity, but a human being. Then one can ask how this reinterpretation is in anyway better than the reinterpretations of say Marxists or colonial ethnological reinterpretation of Hindu Puranas. The answer is simple. In 1983, Ganapathi Venkataramana Iyer, popularly known as G V Iyer directed the Sanskrit movie Adi Shankaracharya. The movie portrayed the life of Adi Sankara without any element of supernatural powers seen in the traditional accounts of his life. Yet, both traditionalists and modernists admired the movie. The reason is because the movie was made in sync with the spirit of the life and philosophy of the seer of non-dualism. Similarly, here, the portrayal of Sri Krishna by Sanjay Dixit bereft of all supernatural elements is still in sync with the spirit of Sri Krishna of Bhagavata and hence this is qualitatively different from, and better than the Marxist or ethnological interpretations.

The novel is more descriptive than illustrative. There is a dictum in storytelling that one should show and never tell. The author seems to have completely ignored that. And the reader can ignore that given the fact that this is the author’s first attempt. One can be sure in the two upcoming novels of the trilogy the storytelling skills of the author will further improve.

Yes. This too is only an interpretation. But what makes this interpretation important is the fact that the dharmic society is facing relentless attacks from the Kutil-dharma like cult-like religions. So this interpretation of Krishna, which has been implicit or involuted in the Bhagavata itself, has been expanded and presented in a modern literary form by Sanjay Dixit in an interesting way. Krishna in Bhagavata is all these and much more. He is of infinite possibilities and he can manifest through infinite ways to provide solutions to the crises that the dharmic society faces.