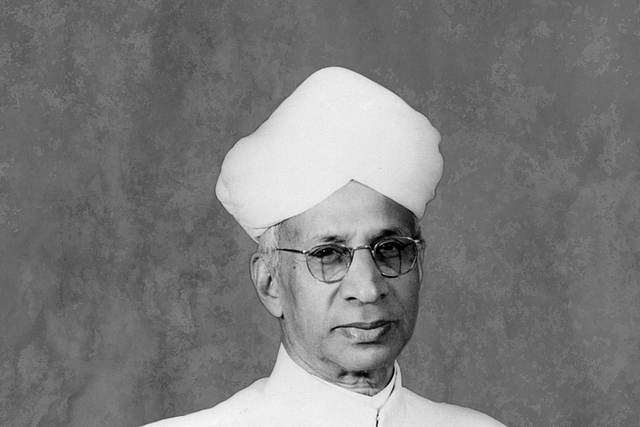

Radhakrishnan For The 21st Century Indian: A Swarajya Heritage Project

As we celebrate Teacher’s Day today on the birth anniversary of Bharat Ratna Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Swarajya Heritage brings to you the ‘Dr Radhakrishnan Project’.

A project that aims to bring the ideas and thoughts of this unparalleled philosopher, scholar and statesman of twentieth century India to you through a series of articles and essays that propound his views on religion, education and civilisation.

Here is an introduction to Part I of the series titled, “Civilisation”.

In the history of our planet, civilisation is a relatively young phenomenon. Yet, in terms of impact, Anthropocene, in general, and the rise of organised human activity --- which we call civilisation --- in particular, has had an impact that is one of the most intense in terms of its almost irreversible effect on planetary ecology.

It is hard to find any other single species that has created such an effect on the life of the planet. Today, we see the march of our civilisation threatening the very web of life of which humanity is but one strand.

So how does human civilisation sustain itself and enrich itself? At one level, it has to be a balance between the human species and the rest of life on this planet. At another level, there has to be a balance between the individual and the collective society.

The Hindu culture came up with the idea of Dharma as the very basis of all human aspirations. Dharma should guide, control and animate all activities.

For Radhakrishnan, this was the most important central axis around which human civilisation should evolve, progress. And this Dharma is not sectarian, it is universal.

Written as far back as in 1929, the essay, ‘Kalki or the Future of Civilisation’ historically stands between the two World Wars, the utter moral failure of the world humanity during the Holocaust and the emergence of human hope in the form of India’s struggle for Swarajya through Satyagraha. So this articulation needs special attention.

One can consider this work as one of the finest expressions on human hope. Radhakrishnan’s humanity “in all its extent and history is a single organism, worshipful in its growing majesty and capable of a progress to which none dare set bounds.”

However, this is an organism that can self-destruct through mutual conflicts. To avoid that fate, we need civilisational unity and that unity has to come “not from uniformity but from harmony.”

When he was writing these essays, the British had made themselves the global policemen – the greatest colonial power that would decide what was right and wrong and which societies were civilised and which had to be civilised.

Dr Radhakrishnan challenges this colonial vision of global one-up-man-ship and interestingly his words are relevant even to this day. He states:

An acquisitive society with competition as the basis and force as the arbiter in cases of conflict, where thought is superficial, art sentimental, and moral loose represents a civilisation of power (<i>rajas</i>) and not of spirit (<i>sattva</i>) and so cannot endure. Spiritual reconstruction alone can save the world heading for a disaster.

At this point let us also remember that Radhakrishnan was writing the essays in this collection decades before environmental crisis exploded on the face of human species as its mega existential crisis.

Yet, he hints at what is to come as the current world civilisation, being run by ‘economic barbarism’, which ‘exploits the economic potentialities of the earth, to spread far and wide material well-being and master the forces of nature for the ends of man’: “… our life will become clogged and our civilisation will perish of its own weight.”

So what is the spirituality that Dr S Radhakrishnan places as the solution?

It is not otherworldly. In fact, he says, it is “science” that “gives us a new vision of the unknown, the eternal towards which we have been blindly groping all these days.”

And it is the underlying cosmic spirit that manifests itself through the laws that appealed to him and experiencing it through art, science or religion is what, he felt, unites the diverse human religious experience and theo-diversity.

So he makes a strong appeal to go beyond the forms of religious plurality, appreciating them and celebrating them but not quarrelling over them while at the same time he urges us to get impetus from the new vision of the universe unveiled by the sciences to harmonise the theo-diversity of our species.

The essay on Dharma, though it speaks of India or Hindustan, provides a basic principle for harmonising the various basic forces of the human individual into society so that it forms the building block as well as the substratum of civilisation.

The essay on ‘The test of civilised life’ makes the place of women in civilisation an important indicator of the civilised nature of humanity.

'The world community' essay speaks of a future world – where again the unification has to go beyond economic and political conveniences. Radhakrishnan says that the world community he envisages “can be sustained only by a community of ideals” that “look beyond the political and economic arrangements to ultimate spiritual issues.”

For this, he feels the need of “a new type of man who uses the instruments he has devised with a renewed awareness that he is capable of greater things than mastery of nature.”

On the whole, the writings of Dr S Radhakrishnan collected in this compilation, are both historically important and act as frames of perspectives for the future of humanity.

In a world of accelerating changes both in technology, worldviews, science and politics, his writings on civilisation have stood the test of time and continue to serve as a beacon for a harmonious future for us as a species.

Read Part 1 of the Dr Radhakrishnan Project on Civilisation: Dharma: The Individual And The Social Order in Hinduism.