Silk Entrepreneurs Not Silk Slaves: How CNN Report Misrepresents Facts

The CNN report undermines women’s strategic contribution to the Indian sericulture industry, and is completely at odds with how it works.

Silk Slaves is a recently released 22-minute documentary produced under the CNN ‘Freedom Project’. CNN describes its Freedom Project thus. “Since 2011 CNN has been shining a light on modern-day slavery. Traveling the world to unravel the tangle of criminal enterprises trading in human life. Amplifying the voices of survivors”.

The cover image of Silk Slaves is of two Muslim women in full black hijab with only their eyes showing. Silk Slaves is about the debt bondage of two women in a silk factory in Sidlaghatta in Karnataka, a district known for its raw silk trade.

The documentary is supported by Polish-based Kulcyzk Foundation and highlights the work of their grantee, Jeevika, an non-governmental organisation (NGO) in Karnataka involved in rescuing bonded labour.

It trails the ‘rescue’ of the two women under the Bonded Labour Act through the official system.

The sensationalisation of the ‘rescue’ case without context to provide the impression to the viewer that bonded labour is endemic to the silk industry is inexcusable as it is grossly erroneous.

The write-up accompanying the documentary blatantly admits to a lack of data on exactly how many bonded labourers are involved in the Indian silk industry.

There are two serious distortions in the documentary on the subject of bonded labour in the silk industry. One is that the treatment is completely at odds with how the industry in India is organised and, as a result, does not really fit the category of “criminal enterprises trading in human life” even if a few people in the industry indulge in unjust practices (which anyway is common in various industries in many parts of the world).

Second, and more importantly, the ‘bondage’ of two women shown in the documentary, while being unacceptable in itself, is unrepresentative of women’s work in sericulture where most women are not ‘silk slaves’ at all but ‘silk entrepreneurs’.

India is the second largest producer of silk in the world after China and there is scope for increased growth even for the domestic market as India imports low grade silk yarn from China to meet the demand.

In India, sericulture is a farm-based agro-industry practised in about 53,000 villages that provides employment to about 6 million people.

Due to its growth prospects, sericulture is acknowledged to have an enormous benefit of employment for adults in a rural family.

According to one statistical analysis, it can generate employment for up to 11 people for every kilogram of raw silk produced, out of which more than six people are women.

Most of the sericulture processes are home and village-based and organised as family-owned enterprises in which adult women and men of the family work together. Even weaving of the final products is often undertaken in village homes and sold to wholesalers (most are picked up from the doorstep of weavers).

The CNN documentary write-up states “in India, the average silk worker is paid less than $3 a day.” It goes on to say “part of the workforce is trapped in bonded labor, a form of modern-day slavery in which people work in often terrible conditions to pay off debt.”

Since most women silk workers in India are not factory-based at all, these statements are not only a misrepresentation of the industry but are perverse for characterising such work as “modern-day slavery”.

Historically, women have had a bigger role in sericulture than men and, even now, form more than 60 per cent of the workforce. Recognizing this, the year 1994 was declared as the ‘Year of Women in Sericulture’.

Through this special campaign, women’s key role in sericulture was underlined. Women build their own family enterprises through their involvement in almost all aspects of the activity that comprise mulberry planting, weeding, manuring, irrigating, leaf picking, leaf transporting and storage, leaf-cutting, feeding, bed cleaning, worm spacing, mounting, harvesting and disinfections.

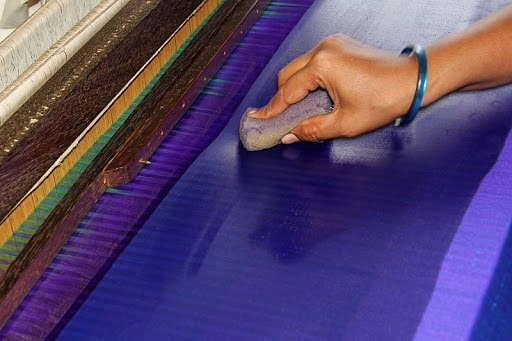

Women are also involved in reeling the cocoons for unwinding the silk filament, and other post-cocoon processes such as twisting, dyeing, weaving, printing and finishing.

The CNN documentary only shows women involved in reeling activities, limiting the view of what women in sericulture actually do and their strategic contribution to the industry that makes them entrepreneurs and not slaves. Many of the activities in the silk value chain are independently profitable.

For example, just the home-based silkworm seed production activity can fetch the woman entrepreneur involved in it over a lakh of rupees (around $1,300). Their industriousness and entrepreneurship in family enterprises have enabled India to reach a prominent position in silk production.

With improvements in mulberry varieties and silkworm species, sericulture has become more remunerative than before and more farmers in more states have taken this up. Twenty-six states in India now produce raw silk which suggests the vast economic scope for the industry being created across India, ably aided by the nodal agency of the central government, the Central Silk Board.

Under the Mahila Kisan Shashaktikaran Pariyojana (women farmers empowerment programme), 36,000 sustainable livelihoods are expected to be created for marginalised women silk farmers.

The key words in the silk industry in India always were and continue to be women farmers, empowerment and sustainable livelihoods.