The Doctrine Of Colourable Order: Can The Courts Do Indirectly What They Can’t Directly?

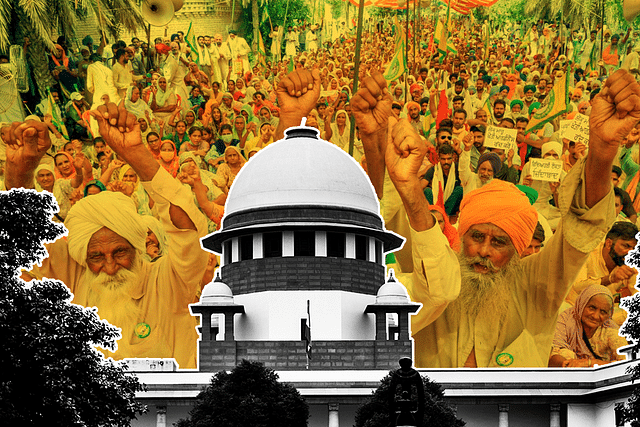

While it is true that the court has stayed farm laws to uphold fair play, it sets a precedent that will encourage protests against government reforms.

The Supreme Court stayed the 'implementation' of the farm laws based on several petitions filed against the laws, and the protests associated with it.

This order of the apex court sets a precedent wherein interest groups are incentivised to go on streets to receive favourable orders from the court. It is problematic since this instance will be cited by the vested groups for stalling reforms brought about by the government of the day.

When a legislation is enacted, it is considered to be constitutional unless proven otherwise. Broadly, the two grounds for unconstitutionality of the statute are that of legislative competence and violation of Part-III of the Constitution which deals with fundamental rights.

In the present case, the Supreme Court has not indicated any glaring unconstitutionality to stay the implementation of the laws. It has cited the Maratha reservation case, wherein the apex court stayed the implementation of the reservation policy brought about by the Maharashtra government through an enactment.

There is a distinction between the two since in the latter there were substantial questions of law relating to the interpretation of the Constitution and more importantly, legislative competence in itself was questioned.

In the present case relating to the farm laws, while there are a few petitions which have challenged the Constitution (Third Amendment) Act 1954, it does not involve a direct challenge to the impugned laws under the present framework of the Constitution.

The amendment challenged essentially transferred matters relating to trade and commerce from the state list to the concurrent list, thereby enabling the central government to legislate on the subject matter.

Hence, unless the court holds the amendment to be invalid, the scope to hold the new farm laws as prima facie unconstitutional does not arise. It would be pertinent to note that ratio decidendi of the court to stay the implementation of the law on the basis of the Maratha reservation case is not free from flaws.

The order states that "this Court cannot be completely powerless to grant stay of any executive action under a statutory enactment". This probably makes an implied reference to Article 142 of the Constitution which effectively provides the top court the power to pass decrees or orders to do complete justice.

While it is true that the court can pass such orders to do complete justice, it has to consider the positions, functions and powers of the other organs of the state on the same subject matter, especially when the Constitution explicitly vests the powers with other organs.

The transgression of such boundaries by violating the doctrine of separation of powers would require higher standards of vindication. In the present case, when there is no statutory void or legislative inaction and the frustrated parties who are bringing up issues before the court have not demonstrated any immediate harm by virtue of implementation of the laws, it is hard to find any justification.

This particularly gives rise to an important question as to whether the court can do indirectly, what it can't do directly? In constitutional law, in order to test the legislative competence of enacting a law on a subject, the court at times invokes the Doctrine of Colourable Legislation.

It essentially means that the legislature cannot legislate on a particular subject matter indirectly, if it is barred from legislating on it directly. It is based on the maxim "Quando aliquid prohibetur ex directo, prohibetur et per obliquum" which means that "you cannot do indirectly what you cannot do directly".

As a matter of record, it is reported that the Attorney General pointed this to the court during submissions. He also added that staying the implementation of the laws is the same as staying the laws in effect.

If the legislative organ of the state is bound to follow this particular doctrine while performing its functions, what provides immunity to the judicial organ from following similar principles?

When we consider the fact that the executive, Parliament and judiciary are creatures of the Constitution, a similar set of principles should govern each organ as it performs its functions. Since the Constitution does not envisage any hierarchical arrangement of the organs, one cannot be considered supreme over the other.

Therefore, if the same doctrine is to be applied to the judiciary, we get the novel 'Doctrine of Colourable Order' which means courts cannot pass orders indirectly on matters which it cannot pass directly.

While it is true that the court has intervened in the present case by staying the laws with an intention for victory for fair play, it definitely sets a precedent which is likely to open up a Pandora's box.

As Attorney General K K Venugopal rightly points out, "Article 142 is treated as a 'Kamadhenu' from which unlimited powers flows to the apex court of the country".

One can only hope that the judiciary respects the boundaries set by the Constitution and allows other organs to continue performing the functions as envisaged in the Constitution.

The time is also ripe for us, as a democratic polity to review the unhindered use of Article 142. Eminent jurist Nani Palkhivala used to argue that Parliament, being the creature of the Constitution, cannot be granted unlimited power to make the creature of the Constitution its master.

Similarly, no other organ, be it the executive or the judiciary, be granted the unlimited power to become the master of the Constitution.