The Spirit Of The Letter: Why Functional Literacy Is Now Passé, And Informed Citizenry, The Need Of The Hour

Was the National Literacy Mission, launched nearly 30 years ago, a success?

Is literacy all about only reading and writing?

Or, is it time for a knowledge-based existence?

Nearly 30 years ago, the Government of India had launched the National Literacy Mission (NLM) with much fanfare. The NLM targeted adults, between 15-35 years of age, seeking to impart to them ‘functional literacy’ through time-bound, volunteer-based efforts and campaigns.

As schoolchildren in Delhi, we had been involved in different ways — as volunteers armed with ‘literacy kits’, and also participated in creating theme songs for the Mission, for which competitions were organised by the Department of Education. We were an enthusiastic lot, ready to do our bit and more, towards making India a more ‘saakshar’ (literate) country.

“Jalaa Gyaan ka Deep karo, Roshan tum apna Desh” (light the lamp of knowledge to brighten your country), and Bina Padhey tum Samvidhan ko samjhoge kaise (how will you understand the Constitution if you can’t read?) — were the kind of lyrics we wrote. Such were the lofty goals we expected the NLM to achieve.

As educated people ourselves, we saw the NLM as the means for emancipation, through which gradually, all people would become active participants in decision-making, and in the process of development. The situation of Gyaan-heen daaridra (poverty that emanates from ignorance) would change.

All this was in 1988, and the mission was largely believed to have played a significant role all along in raising literacy levels in the country.

It came as a surprise, therefore, when one of the key findings of a recent ORF paper titled “Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension – was that India’s older-adults’ literacy rate is currently poor, and this considerably drags down India’s overall performance in literacy.

The ORF paper examines the literacy landscape in India between 1987 and 2017. It finds that overall, literacy has improved.

When broken down into age groups, data reveals that child and youth literacy stand at 93 and 94 per cent, respectively and given this momentum and the priority given to child and youth literacy in the development agenda, the country will achieve universal literacy for children and youth by 2030.

But this progress is offset by the older adults group — with a literacy rate of 73.2 per cent.

They find similar trends when analysing gender gaps in literacy. While female literacy is improving overall — and the gender gap is nearly closing among children and youth, owing to cash-incentives and other schemes and campaigns like Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao — the literacy gender gap remains wide for older adults.

A state-wise breakup also shows that most states have made great strides in improving literacy and reducing the gender gap for children and youth; however, they have not been able to make progress with older adults.

The paper does good service to policy-making, as by breaking down the numbers into age cohorts, it is easier to examine where the problem lies.

What Now — Do We Put Adult Literacy High On The Policy Agenda?

The logical corollary of such a study is to work on the laggard cohorts; recommendations that follow, accordingly, put adult literacy high on the policy agenda.

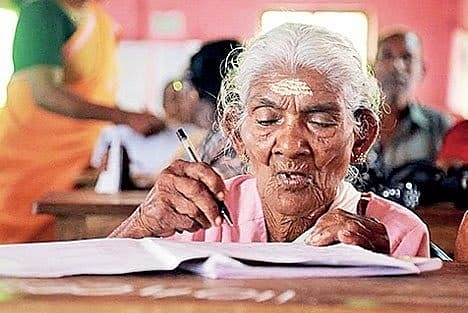

However, the very finding that older adults are still illiterate — in the age-group 25-64 — should give a new perspective to literacy efforts.

If most of those that the NLM 1988 was then targeting are still illiterate (15-35 years then would be 45-65 years now), can the NLM be considered a success? Should literacy efforts be continued, and if yes, in what shape?

It is often suggested that elders at home or in communities be taught by the youth. But would they be interested in learning at all?

The Hakki Pikki tribes-people in Pakshirajapura in Karnataka are a stark example, who feel no need for education.

Illiterate and unlettered, this community nevertheless has at least one globetrotter per family, with several visas, and speaks several languages.

Originally a community of poachers, they are now exporters of animal skin, herbal medicines and decoration items and smartly travel the world, learning new skills, and leading modern lifestyles back home.

What more could education give us? – is their belief.

Indeed, without immediate or tangible benefits, adults do find little utility in learning letters or numbers.

However, with recent news reports of Hakki Pikki youth being exploited by criminal gangs coming to light, activists feel that education is the panacea and have begun working on it.

This is in line with an oft-cited argument like “Illiteracy among older adults is also a pressing concern, as illiterate adults are more susceptible to ill health, exploitation and human rights abuse” (ORF).

But how often we do hear stories of youth educated even up to the secondary level falling prey to greedy contractors’ promises of dream jobs abroad, and burning their fingers badly.

Perhaps, rather than a mere increase in functional literacy, increase in awareness and understanding of rights and duties would better prevent exploitation and abuse.

Literacy And HDI

In fact, in a country where even education standards are suspect — when surveys and random checks have found even Class 8 children unable to add, multiply numbers and read sentences — what would efforts to increase literacy be able to achieve towards bettering human development in the real sense?

Again, a correlation is often made and cited between increased literacy and infant mortality: Most studies link higher female literacy rates with lower infant mortality.

This logic is given as a reason to pump in resources into less literate states, believing that enhancing literacy will result in better parameters of human development.

But such simplistic conclusions in the case of India can be misleading in two ways: One, it will slow down attacking other factors that affect infant mortality like income inequalities, lack of health delivery and neonatal facilities, etc.

And Two, it will result in wasting precious resources, yet again, towards literacy improvement.

One must bear in mind that if more literate states — like Kerala — show lower fertility or lower IMR, a more reasonable explanation is the coexistence of all parameters of development, rather than cause-and-effect.

It is simply a more emancipated and broad-minded society, where higher literacy is also a symptom.

If literacy were really the cause of lower fertility, how does one explain states like Andhra Pradesh, the least literate state with an adult literacy rate of 61 per cent (ORF statistics) whose fertility rate is low at 1.7, the same as Kerala’s.

The Kerala Model: Is It The Way To Go?

Kerala, the most literate state for since we can remember, was overtaken by Tripura and Mizoram a few years ago.

Reportedly, Kerala not only has had to grapple with its neo-literates relapsing into illiteracy, but also an SCERT study reveals poor education standards:

Among Class IV students, 25 per cent can’t write English; 35 percent of Class VII students could not read or write their mother tongue and 73 per cent are poor in basic Math.

This, in spite of 37 per cent of the state’s budget allocated to education, and other favorable circumstances like an oversupply of teachers, decent school buildings, and availability of drinking water and toilets.

If the standard of education in the state is falling as rapidly as in other parts of the country, is there a case for reconsidering such heavy expenditure on education?

Importantly, can Kerala still be considered a model state — and the KSLM efforts be considered scalable?

What could, in fact, be emulated from Kerala is where it all began. Voluntary efforts by a selfless leader like PN Panicker, and his state-wide Library movement — Kerala Granthashala Sangham — was the de facto starting point of literacy; in fact, not just literacy, but also informed citizenry, as the libraries included activities like discussions, debates, seminars, sporting events and farmers’ clubs.

After the state government took over the operations of the Sangham (after which it also went downhill), Panicker went on to found the ‘Kerala Association for Non-Formal Education and Development’ for total literacy, whose volunteers became an indispensable part of the KSLM.

For other states to take a leaf out of Kerala’s experience, they too would first need their own philanthropists — as committed, untiring and selfless as Panicker.

The recent success of Tripura and Mizoram also can be attributed to volunteers, NGOs and local clubs — however, under the close supervision of the chief minister and the SLM.

Needless to say, a real difference in the literary landscape or demography can only come from leader-based efforts within states.

The Central government can have a vision, but the ambition and will, which drive implementation, cannot be imposed from the Centre.

At best, NITI Aayog can constitute a literacy index for states. Whipping up state pride can be a possible hook, and IT associations in states could take the lead in this effort.

Experts feel that the mother tongue is of prime importance and that literacy efforts must focus on this first, and then other common languages can follow.

`Functional Literacy’ Versus Literacy For Various Functions

Health, digital and financial literacy, which are fast becoming indispensable parts to daily living, can also serve as good hooks for overall literacy, as people would see purpose to learning here.

Some opportunities for female literacy are women’s empowerment efforts, like the Ujjwala Yojana that targeted women beneficiaries; and Bhamashah Yojana in Rajasthan for health, where the family card was made with the woman as the head of family.

Job-oriented literacy, through skills training is another one way to achieve literacy, where immediate benefits are available.

ORF recommends that skill training be embedded into adult literacy programmes. Women can especially be targeted to close the gender gap further.

The concept of ‘functional literacy’ — just acquiring the ability to sign, read signboards, and handling money — must be given a burial, as it serves no purpose in development.

Finally, if still the government wants to make dedicated efforts only to improve adult literacy per se, a direct incentive such as meals in night schools — akin to the midday meal scheme that improved attendance and enrolment in school, particularly of girl children — can be given.

Such ‘mid-evening meals’ could specifically target women, by which both nutrition and literacy outcomes can be bettered. This would reduce both gender gaps, in literacy and nutrition.

Such incentives may induce people to also learn the 3Rs, alongside serving their other ‘main purpose’.

Finally, it must be remembered that illiteracy per se is not a bane, but unawareness is, apathy and a lack sense of citizenship is.

Once the lamp of patriotism (regional patriotism included) and citizenship is lit, literacy and education will follow.