Why Modi Government’s Bid To Control Price Of Coronary Stents Hasn’t Yielded Desired Result

Capping stent prices was one of the few socialist policies the Narendra Modi government has implemented in the last couple of years.

The benefits of the policy and its long-term impact remain to be seen.

On 13 February 2017, the National Pharmaceuticals Pricing Authority (NPPA) came out with an order fixing a cap on the price of coronary stents under the Drug (Prices Control) Order 2013. The NPPA fixed the price of bare metal stents at Rs 7,260 and drug-eluting stents (DES) at Rs 29,600. Prices of both stents were revised to Rs 7,660 and Rs 27,890 in February this year.

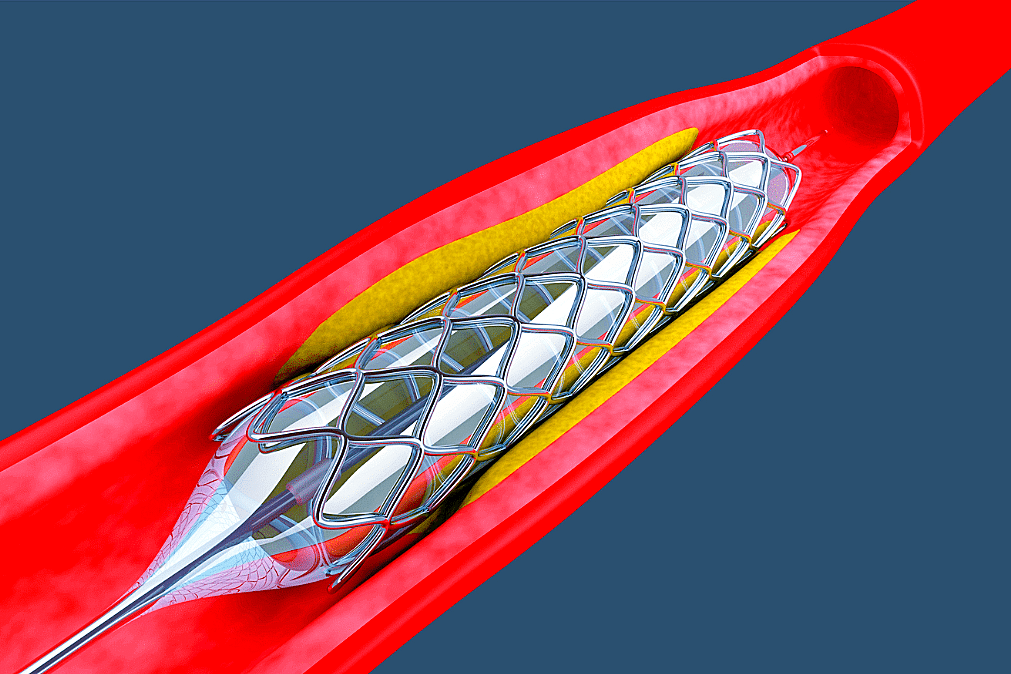

The NPPA’s report on the necessity to fix a cap on prices of stents said that the price difference between the actual cost levied by the hospitals and the landed cost was huge. Coronary stents are used in treating heart attack and blockages, opening narrowed arteries and reducing symptoms like chest pain.

Capping stent prices was one of the few socialist policies the Narendra Modi government had implemented in the last couple of years, including the national health policy. The fixing of the ceiling on stent prices was aimed at ending an unhealthy practice of hospitals getting a fixed amount as a cut from medical equipment companies for using their devices. The NPPA said that the cap was needed since patients were being exploited with exorbitant, irrational and restrictive trade practices, while public interest need to be protected.

The relevance of the NPPA order can be gauged from the fact that coronary interventions to treat heart blockages and other problems are on the rise. N N Khanna and Suparna Rao, in their paper on “Cardiological Interventions in India: The Relevance of National Interventional Council”, said most of the angioplasties done in the country are for anterior interventricular or LAD with a consistent rise in stents to 4.78 lakh in 2016 from 2.15 lakh in 2012. They also said that between 2012 and 2016 coronary interventions have doubled to more than 3.73 lakh. The share of DES had increased to nearly 94 per cent of the total stents used with usage of bioresorable ones beginning to gain acceptance.

The Advance Medical Technology Association, in a study on medial devices, said that stent cost made up 38-40 per cent of the total cost for angioplasty. As a result of the NPPA’s February 2017 fiat, treatment costs for angioplasties had declined 10 per cent to 25 per cent in hospitals across the country. However, the association said that benefits to patients and growth in procedure have not seen significant change in the short-term, while the long term impact remains to be seen.

“Patients getting treated in private hospitals for heart-related problems or getting stents implanted have hardly gained despite the government cap on stent prices. Maybe, the distributor has taken a hit but not the hospitals,” says a medical device supplier, unwilling to be identify himself.

“Procedures involving implant of stent still cost anywhere between Rs 1.5 lakh to Rs 2 lakh depending on the hospital. But actual cost shouldn’t exceed Rs 50,000, including hospitalisation,” the supplier says.

Patients who visit private hospitals cannot expect to gain from the cap on stent prices, says a doctor from Malappuram district in Kerala, on condition of anonymity. “The margin they were getting on stents may not be available any more. But nothing stops them from charging a patient on other heads, say like service charge,” the doctor says.

Those who visit government hospitals could stand to gain if they are asked to foot the stent costs but hospitalisation charges remain the same in government and private hospitals. “The government has capped stent prices, good. But has it prescribed any cap on any charges collected by hospitals? Private hospitals, in particular, can get away with arbitrary charges on patients,” says another medical equipment supplier not wishing to go on record with his name.

One of the reasons why heart patients have not benefited much from the government policies to fix a cap on prices of pharmaceuticals and medical equipment is that hospitals are not ready to give up on their margins. Allegations against private hospitals range from fixing doctors a target for the number of surgeries they need to perform to asking them to advice patients to avail of medicines and implants inhouse. A leading private hospital in Chennai reportedly forced one of its leading surgeons to quit when he refused to tow the management’s line. Initially, the doctor was denied a parking space within the hospital premises before being subjected to various insults, forcing him to quit.

“It’s all a package business in private hospitals now. Any procedure, the hospital comes up with a package,” says a medical insurance adviser. She, too, didn’t want to be identified. “The hospitals can say that we can offer you this stent or that stent and prices are Rs X or Rs Y. Then, they can also prescribe stents that they could term as a specially imported one,” she said, adding that the package costs still remain the same.

Initially, the cap on stent price met with protest from US-based companies like Abbot, Boston Scientific and Johnson & Johnson. The US International Trade Commission, in a briefing, expressed concern since US is India’s largest medical device supplier. Stents from the US made up nearly 45 per cent of coronary stents used in India. The commission said the price cap would put the US companies at a disadvantage. But the fears seems to have misplaced since US companies’ share, particularly that of Abbot, seem to be intact.

“Hospitals have various ways to earn their money. The cut they had to experience in stents is now compensated through the fees they charge for procedures,” says the doctor from Malappuram. That the costs for procedures like angioplasty have not come down is the primary reason why at least 80 per cent of the hospitals have not reported any change in number of persons undergoing the procedure, according to Advance Medical Technology Association.

Following the cap on stent prices, the government has said that it will now come up with trade margin rationalisation for medical devices. The NITI Aayog released a draft paper in June this year to regulate the $10 billion industry. The government could soon introduce a bill on regulating the sector. But the pertinent point is will the ordinary patient be able to derive the benefits given the avaricious nature of private hospitals.