Why The Indian Constitution is Sacred And Cannot Be ‘Dharma-Nirpeksh’

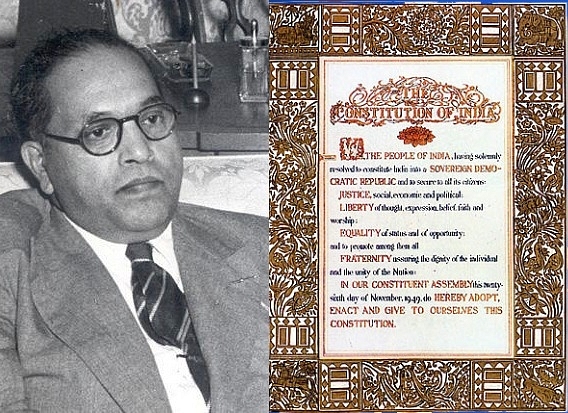

Dr Ambedkar would have fiercely opposed the idea of neglecting the impact of Indic thought and traditions in the Indian Constitution.

Comparing the preambles of the Constitution of both India and United States, one may find a lot of superficial similarities. There is, however, one crucial difference. While the preamble of the American Constitution states that the people of that country have come together to establish justice, the people of India have come together to secure justice.

Eminent jurist R G Chaturvedi explains the difference:

The pledge of the people of United States has been to establish justice, whereas that of the Indian people has been to secure justice. To establish is to set up; but to secure is to make safe or to firmly fix. ...the people of India have recognised and taken for granted the virtue of justice as a primordial reality, and have willed their Constitution to conform to it; but the people of the United States have taken justice as an emergent property of their Constitution and have wished justice to conform to their Constitution. In India, the Constitution is a creature of justice; but in America justice appears to be a creation of Constitution. R G Chaturvedi, <i>State and Rights of Men, </i>1971, p.199)

The concept of the ‘virtue of justice as primordial reality’ is an Indic concept that has been verily embedded in the fabric of our civilisation. Vedic seers called it Ṛta. In the human context, Buddha called it ‘Dhamma’, also known as Dharma. Dr Ambedkar saw the social and political democracies not just as socio-political systems but as manifestation of Dharma-Dhamma in the social realm, and hence a way of life. He considered Upanishadic mahavakyas as the best possible spiritual basis for social democracy.

So, whenever freedom was threatened by its enemies, Dr Ambedkar pointed to them that they were not just opposing a form of government, but they were subscribing to a value system alien to Indic spirit. In 1949, as the head of the drafting committee of Indian Constitution, Dr Ambedkar had to face the attack of Communists.

The condemnation of the Constitution largely comes from two quarters, the Communist Party and the Socialist Party. Why do they condemn the Constitution? Is it because it is really a bad Constitution? I venture to say ‘no’. The Communist Party want a Constitution based upon the principle of the dictatorship of the proletariat. They condemn the Constitution because it is based upon parliamentary democracy.

The Socialists want two things. The first thing they want is that if they come to power, the Constitution must give them the freedom to nationalise or socialise all private property without payment of compensation. The second thing that the Socialists want is that the fundamental rights mentioned in the Constitution must be absolute and without any limitations so that if their party fails to come to power, they would have the unfettered freedom not merely to criticise, but also to overthrow the government.

Then he went on to give a brilliant defence of Parliamentary democracy. He saw the roots of present democratic system he was defending in the fertile soil of pre-Buddhist Indian past. To him the Buddhist Sangha adapted and perhaps improved upon the democratic system of pre-Buddhist and hence Vedic India:

It is not that, India did not know what democracy is. There was a time when India was studded with republics, and even where there were monarchies, they were either elected or limited. They were never absolute. It is not that India did not know parliaments or parliamentary procedure. A study of the Buddhist Bhikshu Sanghas discloses that not only there were parliaments – for the Sanghas were nothing but parliaments – but the Sanghas knew and observed all the rules of parliamentary procedure known to modern times. They had rules regarding seating arrangements, rules regarding motions, resolutions, quorum, whip, counting of votes, voting by ballot, censure motion, regularisation, res judicata, etc. Although these rules of parliamentary procedure were applied by the Buddha to the meetings of the Sanghas, he must have borrowed them from the rules of the political assemblies functioning in the country in his time.

Is it any wonder then that Dr Ambedkar rejected the inclusion of the words ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ into the preamble of the Constitution?