Why Slums Need A Makeover, Not A Move-Over

“The most successful fighters come from slums; all the fighters who come from the slums are successful” – Mike Tyson, 29 September 2018. This, coming from a slum-insider and a celebrity, suddenly adds an interesting dimension to slums, if not glamour. What within slums would make for successful fighters? Is it pure brawn-and-brawl instinct, or a survival-of-the-fittest conditioning, or an intelligence that knows to make the best use of resources?

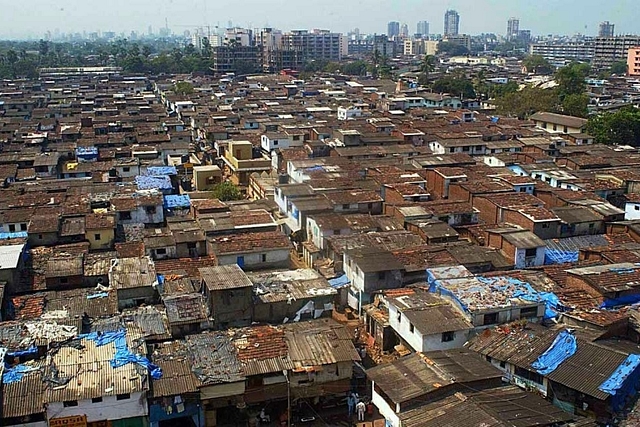

In India, we have seen slums each time we step out of the house, in every commute, run-down tenements occupying areas big and small. According to the 2011 Census -- unfortunately the latest figures that are available -- 65 million people in India live in slums, which is 5.41 per cent of the population.

Some selected high-slum population states are:

And selected low-slum-population states:

These figures were already debatable, with other estimates pegging the slum population at 93 million, rather than 65 million. With growing urbanization, slum populations are expected to have grown manifold after the Census -- and will continue to grow, unless something dramatic happens to prevent them.

Large slum populations are a problem – the “slum” being the operative part, because slums by definition mean small, overcrowded areas, where people don’t own the land and usually pay no taxes. Unfortunately, with governments and local bodies not provisioning for them in urban plans, they have come become symbols of neglect, characterized by squalor, poor sanitation, open sewage, scant water supplies, and consequently, as places that breed anti-social behavior and crime. With this avoidable dimension taken away, slums would cease to be viewed as socio-economic “problems”.

Governments’ policy response over the decades, as is the case across the world, is to provide affordable housing to the poor, and make cities “slum-free”. Yet, these efforts have seen very little progress, and the issue remains unsolved.

The Smart Cities Mission in India, which intends to use ICT to provide solutions to several issues covering efficient energy, waste management, transport, health, safety and so on, in a 100 cities, also has as its thrust the development of “Slum-free cities”, with plans to redevelop slums and provide affordable housing to the poor. Some of such projects in some Lighthouse cities are:

However, a report by AmCham and PWC, titled ‘Snapshot of projects under the Lighthouse Smart Cities’, which sought to track progress of the projects under Smart cities found that though progress was being made on various fronts in these cities, there was no movement on the Slum Rehabilitation projects. This included Pune, which has achieved maximum progress and raised money via bonds with several projects tendered or even completed. A fact check here for tenders in the Pune Smart City portal, also shows no tenders in this area.

If at all any updates have come on this front, it is about protests by slum-dwellers in Smart cities, when they were told to move because a project was to come up where they lived.

Why do slum-dwellers resist resettlement or alternative housing programs, when ostensibly they will be the solution to their substandard and ad-hoc living solutions? This is because slums being seen as eyesores are sought to be removed to remote areas of the city. This results in the dwellers’ spending a large part of their earnings to work. Even in widely-lauded projects such as Sabarmati Waterfront in Ahmedabad, as this paper by a research team of CEPT (Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology) had pointed out, had resulted in “constrained mobility and stressed livelihoods created by displacement and resettlement to sites like Vatwa”. This, the authors had termed as a form of “structural violence inherent in the development paradigm”, which results from material deprivation, inequality and exclusion. This move to a new place had led to several dropping out of the workforce, rather than spend on transport to go to old workplaces; or take up lower-paying jobs. The study also found that peripheral locations also lack social amenities, water and sanitation always reached later, and often the construction quality of the new dwellings was poor. Crime is also usually high in the periphery, leading to fear among women and children.

Slums as a Solution

Indian slums are mostly anti-theses of planning, cleanliness, amenities and regulation – and for all the development in cities, no thought is really given to making the lives of the dwellers better. Eyesores, no doubt.

But, who are the slum-dwellers who live in these eyesores, the slums that we with look upon with disdain? The same people who, when they don’t turn up, our lives get disrupted: the cleaner, the cook, the newspaper vendor, the milkman, the gardener. Dharavi, the famous Mumbai slum, is a hub of enterprise and small businesses as many know. This detailed story, titled ‘Mumbai’s Smart Slum’, goes a step ahead to tell us that “Dharavi residents also recycle much of the city's trash, leaving experts to believe that Mumbai would quickly be buried in its own refuse without its help.” Dharavi is known to be a hub of enterprise, home to many cottage industries, and a symbol of aspiration, dynamism and optimism. The author skillfully argues that Dharavi residents must be engaged in the process of development, rather than top-down development models that begin with bull-dozing their structures.

Despite all these aspects that make slums integral to our lives and sustenance, the attitude towards them and the consequent neglect make them prone to illnesses like dysentery, cholera and danger in times of extreme heat and rain.

Makeover rather than Move Over

Smart Cities could instead provide for upgrade of slums -- what is known as in situ development -- while making residents part of the planning process.

The place to begin would be land rights, and here, Naveen Patnaik, Orissa Chief Minister set a record in June this year by giving slum dwellers land rights and other amenities. Patnaik was quoted as saying, “We had to choose from continuing the practices of evictions and treating slum-dwellers as encroachers or recognizing their immense contribution to the life of the city… We chose the second option”.

This fits in with Deepika Andavrapu’s dissertation findings on “Resilient Slums” at the University of Cincinnati, School of Planning.

The author says that instead of adopting the policy narrative of the “slums as a problem” genre, which felt the solution must be demolition, the narrative must now shift – and even beyond seeing them as a solution. In the “enablement” genre, the policy narrative shifts towards partnership with the poor, which grassroot organizations and NGOs must help out with. She cautions against moving residents to public housing in a hurry, as the disruptions may result in increased distrust and no longer seeing the system as benign; also. Also, substituting the slums with a high-rise building results in a loss of the neighbourhood effect and with street-level interactions no longer a part of daily living, quality of life is affected.

Ultimately, it boils down to believing that the strength of the chain lies in its weakest link. And that applies to smart cities, too. Is there scope to use ICT to make existing slums smart? Can the skills and ideas of slum-dwellers -- many of them painters, constructions workers, plumbers, carpenters -- be utilized for their own interest? Can NGOs who are already familiar with the social construct and requirements of particular slums be involved? PPP models have proved effective world over, rather than government’s own finances. But all this will need to be preceded by the right attitude: the Sun shines equally on all; the governments and local bodies must adopt the same equality of grace towards all their citizens.