A True Renaissance Man of India

A couple of months ago, I was attending a Carnatic music concert. My daughter was sitting next to me. The singer announced that the next melody would be Kurai Onrum Illai which was composed by Rajaji. My daughter looked at me and said “How many things did he do? Was he also a composer?”

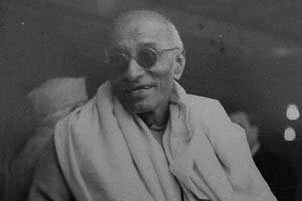

I kept thinking of Rajaji—Chakravarti Rajagopalachari—a Renaissance human being in every sense of the term. He was a lawyer, a politician, a writer, a composer, a translator, a political philosopher, a man who combined a life of action and a life of letters—and who left India and the world a richer place. I kept wondering that even a fraction of these achievements would qualify for greatness.

I was and am not ignorant of his weaknesses. His persistent lack of a genuine popular political base—he depended on Gandhi, Nehru and the proverbial Congress “High” Command to get himself foisted on to the Madras Congress Party; he was accused of “backdoor entry” as he preferred a “nomination” to the Legislative Council to an election to the assembly; his views on Prohibition were derived from Gandhi and smacked of an authoritarian streak in an otherwise libertarian persona; his opposition to the BCG vaccine was a trifle outlandish; his support for Hindi in 1937 and his opposition to Hindi in 1967 may indicate a certain vacillation and lack of lucidity which rarely affected him otherwise; his willingness to sacrifice his government for an obscure (and possibly obscurantist?) and definitely trivial position on school education, betrayed a lack of realism, which again, one could rarely accuse him of. Net-net—he was by no means perfect. He had his weaknesses and a certain streak of ruthless opportunism. But on balance, his insights, his courage, his farsightedness and his patriotism were of such a high order that one is left breathless thinking about them.

Many in the Congress disliked him for opposing the Quit India Movement. But today, revisionist historians concede that his may have been the smartest move of all. To oppose Britain in the midst of a titanic struggle against Fascism, to play into the hands of Japanese militarists, and to concede space to Jinnah’s new-found religion-based politics—all of these were outcomes of the Quit India Movement. Rajaji was extremely intelligent and farsighted in appearing to concede Jinnah’s claims. But the Chanakya in him is now apparent to us. The Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal has noted that the district-by-district referendum on Partition, which replaced the slogan of religion-based nationalism with territory-based decision-making was the only real way to counter Jinnah.

Rajaji was always on the side of moderation and realism. Many are not aware that he pleaded with the Nizam to be realistic and in return was quite supportive of a compromise solution for Hyderabad, rather than a confrontational one. He was also, along with Minoo Masani, one of the least xenophobic and maximalist Indian leaders when it came to Kashmir. He never believed in the need for endless adversarial relations between India and Pakistan. Again, rather unfashionably for the times, he opposed a harsh approach to the Naga issue and referred to the Nagas as a “brave” people.

The only people he was absolutely determined to oppose were the Communists. He referred to them as his “enemy no.1”. He was unhappy about our betrayal of the people of Tibet and was convinced that we as a country should join the western alliance of those days against Communist China. Today, almost three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Rajaji’s views appear so prophetic, so sensible, so timely.

Rajaji’s economic views stemmed first and foremost from a moral perspective. A clientilist state which is in the business of distributing largesse, is bound to become a corrupt one. Hence he coined the expression “Permit-Licence Raj”, a dispensation which was more corrupt and inimical to India’s moral and economic regeneration than the much-maligned British Raj, which it replaced. If only the country had listened to Rajaji, we would today be a richer, more prosperous, less corrupt land. But that was the tragedy of the Swatantra Party—they were right, but before their time. Tragically for us, they turned out to be like Cassandra, who predicted correctly, but was not believed by the Trojans.

But if Rajaji had never entered politics, he would still be a towering giant of 20th century India. He first published in Tamil, his version of our two great epics: the Ramayana was Chakravarti Tirumagan—The Emperor’s Divine Son; the Mahabharata was Vyasar Virundu—the Feast of Vyasa. Subsequently, with the help of his college friend Navaratna Rama Rao, he translated these classics into English. For Tamil-speakers, Rajaji’s works still constitute one of the high points of the literature of a language which has literary achievements of the highest order going back to antiquity. Between Kamban’s Ramavataaram and Rajaji’s Chakravarti Tirumagan, the Tamil language has the distinction of a brilliant epic poem and a limpid prose masterpiece.

The writer Girish Karnad has written about the influence Rajaji’s English Mahabharata had on him as a teenager. Karnad’s haunting play Yayati would not have been possible if he had not read Rajaji in his younger days. Rajaji’s rendering of the Tirukkural is a slim book that I keep with me and refer to every now and then. Rajaji understood that Valluvar and his work were almost like friendly living companions for all Tamil people. Rajaji sought to extend this family by letting in those who did not know Tamil into the pithy aphoristic courtyard that Tiruvalluvar created for us thousands of years ago. Rajaji chose a role as a translator, a re-teller and interpreter consciously. It is a pity that he did not pursue his own creative writing with equal energy. We would doubtless have had a Bunyan or a Stevenson of our own.

But almost without trying, Rajaji emerged as an extraordinary writer of English prose. His regular columns in Swarajya magazine dealt with contemporary political issues. But the luminous quality of his prose, his absolute commitment to the simple phrase, the comprehensible idiom, his refusal to indulge in bombast—a favourite weapon of polemicists—all of these ensure that even today, far away from the issues of those times, we can still read with delight and enjoy the wise old man’s sober judgments and gentle chastisements. Rajaji has himself mentioned that he was an admirer of Boswell. One can certainly see the influence of the great English prose stylist in Rajaji’s essays.

And then to music. In the southern Indian Carnatic school of music, we have a strong view that the melody of the Raga is incomplete without the sahityas or words of the lyrics. There is no such thing as a pure melody—if a master vaageyakara has not infused the raga with poetic words. And it is a historical accident that the lyrics/words of most of our classical compositions are in Kannada, Telugu or Sanskrit. While there have been noted and illustrious exceptions to this rule, the Tamil writer in Rajaji came out when he decided that he was going to change the landscape through personal intervention. Even the most chauvinistic traditionalist connoisseur would have to grant that listening to a well-rendered version of Kurai Onrum Illai results in Lord Krishna appearing before us as we close our eyes.

And let us not forget that for all our traditional composers, this and this alone was their sole objective. They were least interested in aural aesthetics or technical brilliance as ends in themselves. If the music did not result in Rama or Krishna or Vittala or Bhuvaneshwari coming alive before our inward eye, then that was not the music we should have. For having created this possibility in his beloved native Tamil—for this alone if nothing else, Rajaji will remain an immortal for Tamilians and for those who seek the touch of Krishna.

When he decided to set up the Swatantra Party and oppose the Congress, Rajaji’s Brahmin antecedents were mercilessly attacked by the spokespersons of the Congress. His adversarial exchanges even with the sharp-tongued E.V. Ramaswami Naicker in the 1930s had never had this element of vituperation.

People forget that while he may have been born a traditional Tamil Iyengar Brahmin, he was in the lead in the anti-untouchability movement of his political guru, Mahatma Gandhi. And the acid test of being casteist or not of course, rests in the institution of marriage. Rajaji’s daughter married, with her father’s blessings, far far away from her Iyengar roots. This alone should put to rest the ill-conceived view that Rajaji was just another Brahmin. A sorrowful EVR turned up at Rajaji’s funeral; when Annadurai died, Rajaji made a speech that Annadurai had earned an old man’s love which was “tough”, unlike the love of the young. A better tribute from an older leader to a younger one can rarely be found.

Rajaji would have been unhappy if State patronage had been used to keep his name alive. The so-called socialist cliques which have, sadly, been in control of our country for so many years, have studiedly and consciously ignored the Rajajis and Masanis of our country. It is up to us to ensure that this travesty of our history does not succeed.