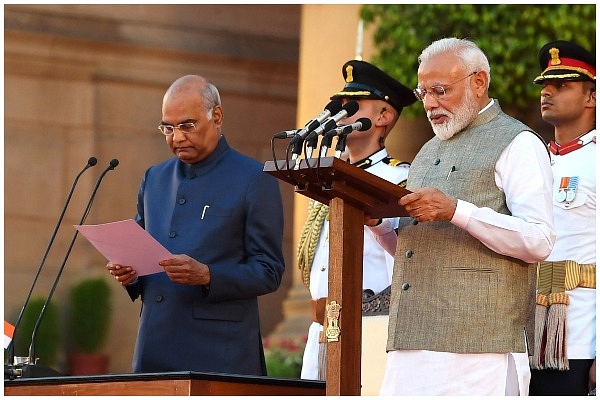

The 2019 Mandate And Its Challenges

Narendra Modi’s big win brings with it the huge challenge of rising voter expectations that need fulfilling.

Here’s what he may need to do.

The massive mandate for the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) in the recent Lok Sabha elections can easily be put down to two key factors: Narendra Modi’s huge popularity, and Amit Shah’s ground support, including his ability to get the party machinery to work to bring in the votes. However, this would be less than half the story. The real factor that propelled the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) past the 300-seat mark, and the NDA past 350 is the electorate’s decision to teach the opposition a lesson it won’t forget.

The mandate is thus both a positive vote for Modi and a negative vote against opportunistic alliances. The latter ensured the defeat of arithmetic- and caste-based mahagathbandhans or alliances in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Jharkhand; their collective caste and community bases were neutered with the NDA garnering more than 50 per cent of the total votes cast in most states.

In roughly half the states, the NDA polled more than 50 per cent of the vote, and in three of them (Gujarat, Himachal and Uttarakhand) it even crossed the 60 per cent mark. You can’t get a bigger mandate than this in ultra-diverse India. This electoral performance suggests that Modi may be the unifier-in-chief rather than the divider-in-chief, as one global magazine headlined its cover story, but the real determination of the voter was manifest in how she showed the opposition the door.

Contrast this with the reality just six months ago, when the Modi government’s economic underperformance was beginning to show (growth slowdown, farm distress, no investment or jobs nirvana), and there was a degree of fatigue with its politics. If, despite this, the average voter completely reversed her judgement of the December assembly polls, where the BJP lost three major Hindi-belt states, one can only speculate that there must have been extreme voter disgust with the opposition that she went the whole hog with Modi.

The anger against the opposition was enough to over-ride the caste-and-communal arithmetic of the Uttar Pradesh partnership of Mayawati and Akhilesh Yadav, the enticing promises of the Congress party’s NYAY (Nyuntam Aay Yojana) that promised the bottom 20 per cent of the population Rs 72,000 per annum as guaranteed income handout, and the extreme hostility of the mainstream English and international media, which saw nothing good in the Modi government.

It was the dissonance between the experienced positive reality of the poor as against the negative propaganda unleashed by anti-Modi politicians and the media that may have been a key trigger for this huge vote for the BJP-led NDA. The smartest thing Modi did in his five-year tenure was to offer all his pro-poor policies on an extraordinary scale: near 100 per cent coverage of bank accounts for households, 12 crore PM Kisan Samman beneficiaries (Rs 6,000 in cash to small and marginal farmers), seven crore Ujjwala cooking gas allocations, nine crore toilets built under Swachh Bharat, and 50 crore potential beneficiaries in Ayushman Bharat, the scheme that offers Rs 5 lakh of medical cover for poor households.

Given this kind of scaling, it is impossible to believe that some benefit has not touched nearly all people somewhere or the other. When you get a benefit, howsoever small, or if you see someone near you get the same, and you have no reason to think you will be excluded, it is hard to believe that you should vote against the man delivering all this without a strong reason to do so. The opposition did not provide it. The dissonance between what voters saw with their own eyes and what they heard the opposition leaders allege would surely have convinced them to place their trust in Modi. Hope usually trumps bile and negativity.

If this explains Modi’s renewed mandate for 2019-24, what should worry the Prime Minister is delivery. If so many people across the length and breadth of the country have reposed extraordinary faith in you, the expectations are bound to be scary. And whatever you have to deliver has to be delivered in an atmosphere where your closest allies will be suspicious of your power and intentions, your enemies, presently in shock, will be looking for the first opportunity to pounce on your every mistake, and the discredited parts of the media will begin to air up old narratives of intolerance and violent Hindutva — something that has already begun.

At the time of writing, the English language media was drumming up an incident in Gurugram, where a Muslim was allegedly beaten up for wearing a skullcap and forced to chant Jai Shri Ram. Narendra Modi should rest assured that, henceforth, any minority or Dalit Indian slipping on a banana peel in any part of India will be seen as his failure to empathise or even prevent that fall. After all, wasn’t Swachh Bharat supposed to ensure that garbage is placed in the right place, and not the middle of the road for the unwary minority citizen to slip on?

A key element of the 2019 mandate was the failure of the opposition to capitalise on the NDA’s major underperformance on the farm and jobs front; while this did not deter the voter this time, in 2024 it will be the economy and experience of ‘achche din’ that will matter. The economy cannot be ignored forever and buried under the successes of Balakot or nationalism or the delivery of small benefits to the last man staying at the last mile. The one thing all voters forget is what they got before the last election.

At another level, Modi and Shah will also have to deliver something to their core constituency — the conscious Hindu who has been a consistent BJP supporter. Of the BJP’s vote share of around 38 per cent this time, one could say that 15 per cent would be a core BJP vote, who will never think of voting for any other party. It is this constituency that enables Modi to sell his policies to other Hindus, who may be less convinced about the BJP’s cultural and religious stance, in order to make a winning combination.

Apart from Ram Temple, the BJP this time will have to convince its core voter that it has not become a carbon copy of the Congress party in its pursuit of power. This core group was pretty disillusioned by late 2018, but thanks to the negative campaigning by Modi’s political rivals, they had no option but to bat for the BJP. At the end of the day, the core BJP voter knows that the alternative to Modi is a rabid minoritarian group that is Hinduphobic to its vitals. In short, the core BJP voter backed Modi 100 per cent this time because the alternatives were worse. It was about self-preservation.

If one accepts this backdrop of political and economic challenges for Modi in his second term, it follows that the Prime Minister will have to deliver on several fronts — cultural, political and economic — at the same time. Given below are his key challenges, and possible solutions. Let’s begin with his political challenges.

#1: Managing his allies: Strong allies like Shiv Sena and Janata Dal (U), and smaller ones like the Lok Janshakti Party, Akali Dal and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) will be worried about the fact that Modi does not need them to manage the country. While it may not be possible to satisfy everyone with plum cabinet posts, both Modi and Shah need to constantly engage the allies to see if they can be helped in ways where they can maintain their political relevance. The simple law of ally management is this: the less you need them, the more you need to manage the relationship. This failure almost cost the BJP its Shiv Sena alliance before the general elections. No such mistake should be repeated in the next five years. The AIADMK, which won only one Lok Sabha seat, has 13 Rajya Sabha members and hence not exactly a useless member of the NDA. To keep the flock together, it may be useful to give the core group of allies an audience with the PM once a month or even two months.

#2: Managing the opposition: A demoralised, defeated and bruised opposition will be less inclined to cooperate with the government, especially when their numbers are needed to pass important legislation in the Rajya Sabha. The honeymoon period for the government will not last beyond this year, and so it is best to reach out to the opposition quickly so that they can be signed on for backing crucial legislation on land and labour reforms in the first two sessions of the new Lok Sabha. Once the timetable for state assembly polls gets set after September, everyone will be in election mode, and it will be tougher to get opposition support on important bills. Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir are due later this year, and in early 2020 we have the Delhi assembly polls, and after that Bihar. So, it is best to strike deals with the opposition when they are still shell-shocked and unable to oppose the government easily.

#3: Touching base with the core: The BJP’s core constituency is the Sangh and the Hindu voter who identifies himself or herself as Hindu. This constituency got almost nothing for its efforts during 2014-19, despite doing their best to put Modi in power in 2013-14. To be fair to Modi, it was not easy for him to live up to his ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas’ slogan against a fusillade of condemnations and abuse by the intolerance brigade and award wapsi gang, in order to pander to his core Hindu constituency. But it may be equally true that he did not even attempt to direct resources to areas that did not threaten his main objective of positioning the party to the Centre-Left economically so that its base among the poor grows. What, for example, prevented the Modi government from dedicating a few hundred crores to set up, say, an Indic version of JNU, created to develop the necessary intellectual capital to take on the Left? What, again, prevented the government from bringing in a law to negate the Supreme Court’s Sabarimala judgement, which no Keralite party barring the Left could have opposed? The Modi government failed to do these small things that could have helped convince the core of its sincerity in furthering the cause.

#4: Articulating Hindutva: One of the BJP’s long-term goals ought to be the positioning of the party as one that defends Hindu interests, but without contravening the Constitution and its basic features. The BJP has no future if it does not define itself as a Hindu party, just as the Muslim League or the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) do so as Muslim parties or the Kerala Congress as a Christian party, or the Samajwadi Party as a Yadav-based party. If these parties can exist, so can the BJP as a well-defined Hindu party. Instead of allowing the opposition to define it as a party that backs lynch-mobs or abuses Muslims, the BJP must define its Hindu core clearly — without making it anti-minority. A party that does not seek to define what it stands for will get redefined by its enemies. Luckily, while this has indeed happened with the BJP in the past, so far it has helped the party. Many Hindus began to believe that the BJP was their party by default, even though the BJP has actually done little to defend Hindu interests, whether in terms of freeing temples from state control, reworking articles 25-30 to ensure that the majority community does not get excluded from their coverage, or by rejigging laws like the Right to Education Act so that they are made voluntary and incentive-based, and not loaded onto majority institutions as a form of social obligation. The Citizenship Amendment Bill, a last-minute signal to its core case, fell between the cracks as the party failed to explain its logic both to its voter base in the North East, and to the opposition parties which depended on the minority vote. Even the Shiv Sena and the JD(U) refused to back it. Clearly, the BJP cannot get anywhere without defining its core philosophy and working on its allies to get their support — possibly by doing deals on other legislation.

#5: Relationship with minorities: Defining your core is vital to defining a sane and sensible working relationship with India’s minorities, especially Muslims and Christians. The BJP, by not defining its core philosophy, is falling into the same trap as the Congress after Independence, which assumed that it only had to induct a few Muslims in ornamental positions to prove it can represent them as well. Mahatma Gandhi thought that by backing the Khilafat movement, the Muslims of India would become his followers, but that did not happen. The only thing Gandhi managed to produce by his policy of bartering Hindu rights to buy Muslim support was a (Nathuram) Godse. The Congress under Nehru thought that ‘nationalist’ and ‘socialist’ Muslims will be able to sell the party line against Partition to Muslims, but they failed miserably. The BJP too has had its token Muslims, from Sikandar Bakht in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s time to the Mukhtar Abbas Naqvis and Shahnawaz Hussains in recent times. But this is not going to get Modi any kind of worthwhile Muslim support. If he wants it, he must first make it clear that the BJP is largely about Hindus, and then negotiate with parties that truly represent Muslims, or create a block of independent and modern Muslims to negotiate with while formulating national policies. While economic policies do not differentiate between beneficiaries no matter what their religion, in politics you need to be clear who you represent. The BJP should accept that it does not represent Muslims or Christians, who voted in large numbers to defeat it. The only way out is an honest coalition of the BJP with non-Hindu parties — of the kind that exists in Malaysia or even Kerala. A rainbow coalition headed by the BJP. The BJP cannot deliver ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas, sabka vishwas’ if it does not even represent Hindu interests.

#6: The economy: The Indian economy is not firing on all cylinders, and growth is tapering down. Industry is still adjusting to lower leverage and a better tax-compliant status, while the informal sector is feeling the strains of formalising itself. Banks are yet to recover fully from the bad loans crisis, and both agriculture and industry are in some distress. This means the immediate need is to recapitalise banks, and reflate the economy so that growth, consumption and investment get a push. Without a growth uptick, there is not much chance that we will get back to the virtuous cycle of higher savings, higher investment, and higher incomes and growth. For this, both fiscal and monetary policy need to be in expansionist mode, and not in inflation-restraining mood. A small slippage in the fiscal deficit (0.3-0.5 per cent) should be acceptable in 2019-20, and interest rates need to be eased by at least 0.5-0.75 per cent quickly by the Monetary Policy Committee. This revival will give space for longer term reforms and legislation.

#7: Factor market reforms: Ever since India liberalised its economy in 1991, capital constraints have been eased, but the land and labour markets continue to cry out for reforms. If capital is easier to source than labour or land, then entrepreneurs will use more capital than labour. This is key to understandings why despite 6-7 per cent gross domestic product (GDP) growth, the job market has not rebounded over the last five years — in fact, over the last 15 years. While demonetisation and the goods and services tax have acted as further speed-breakers to growth, homoeopathic doses of labour reforms — changes in the Apprentices Act and allowing all sectors to offer fixed-term labour contracts — have not created any huge additional demand for labour. The job market is skewed towards very high skills, or very low-skill, low-quality jobs. The middle sector of good-quality jobs, of the kind the telecom, banking and IT sectors provided until recently, is being hollowed out by capital and technology infusions. We need reforms in labour and land laws to ensure that jobs grow at least half as fast as GDP.

#8: Agriculture: India’s most unreformed sector is agriculture, which is waiting to shed jobs, but the kind of unfree markets it operates in makes it impossible for it to become a vibrant sector of the economy. Agriculture needs investment, and the resources cannot be found unless it sheds labour, and invests in greater productivity and develops long-term export markets. The recent slowdown in rural consumption and low-income growth is largely the result of over-production in some crops, which has depressed prices in the absence of a truly national or international market for output. Agriculture needs state support in infrastructure, irrigation, cold chains and other support structures, but more than anything else it needs to be free to build its own markets. Loan waivers and minimum support prices cannot do the trick of making farmers prosper. To double farm incomes and make agriculture most market-savvy, state-level Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs) need to be dismantled, and farmers allowed to sell their produce anywhere. The middlemen who control APMCs need to be divested of their purchase monopsonies. Once prices are freed, the only small segment that may need subsidising will be the urban poor, who can be given cash subsidies to buy their foodstuffs from the open market. A Shramik Samman to complement PM Kisan Samman?

#9: A robust privatisation policy: A strong economy needs a robust banking and financial sector, and India’s public sector banks — which account for 70 per cent of the total — are nowhere near good health. They have been a drain on public resources, and need frequent dollops recapitalisation. Narendra Modi needs to shed his innate reluctance to privatise by selling at least some of the public sector banks after deciding which ones to keep and consolidate in the public sector. Four or five big public sector banks should be enough for a country of India’s size. But privatisation needs to focus not only on the financial sector, but aviation, telecoms, and others too. Air India’s privatisation should be fast-forwarded, and so too the listing and later privatisation of Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited.

#10: The goods and services tax (GST): The GST, as it now stands, is simply too unwieldy and complicated. We have a multiplicity of rates, and a cess above that, and within some rate bands, we have sectors that get input tax credit and those that don’t (restaurants, real estate). And outside the formal rate structure, we have lakhs of small companies that opt for a ‘composition scheme’ under which they pay a lumpsum tax on turnover and not on final sales. Petroleum products continue to stay out of the GST net, complicating the regime even further. These exceptions repeatedly break the GST value chain that is the key to higher revenues. If there is one single priority for 2019, it should be making GST less complicated, with rates being cut and reduced to just three. To help those small companies who find compliance difficult, the GST Council should, if necessary, offer them free or low-cost return filers for the next three years. This way, those whose only problem with GST was compliance, and not the rates, will grab the opportunity to get into the net.

#11: Statistics and data: It is clear that our statistics system is broken, and the data produced is either too late or too riddled with contradictions to be useful in policy-making. It is worthwhile for the Modi government to invest a few hundred crores to set up an independent statistics commission and create new data bases that are both credible and frequent. The National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) needs to be revamped and empowered, if needed through partnerships with private data gatherers. You can’t solve the jobs problem if you don’t know whether jobs are growing or shrinking; you can’t decide what kind of subsidy interventions you need on the farm or the urban sector if you don’t know the actual levels of incomes earned, or the constraints to higher consumption. We need monthly jobs, prices and production data, and quarterly series on GDP that are believable, among other things. We also need to be able to use big data sources — like the data pouring into the GST Network — to gather real-time economic intelligence ahead of the NSSO’s formal data generation.

In terms of broader goal-setting, the Modi government would be better served if it focuses on jobs as its central goal over the next five years. It does not matter if the GDP stats look weak or the IIP flounders in any quarter. As long as jobs are growing robustly, one can be sure that the economy is going in the right direction.