The Idea Of Hindutva

The war to regain national sovereignty started by Shivaji found a mention in BJP’s battle of 2019. The space for Hindu nationalism reopened in colonial India is being distantly explored in Narendra Modi’s India.

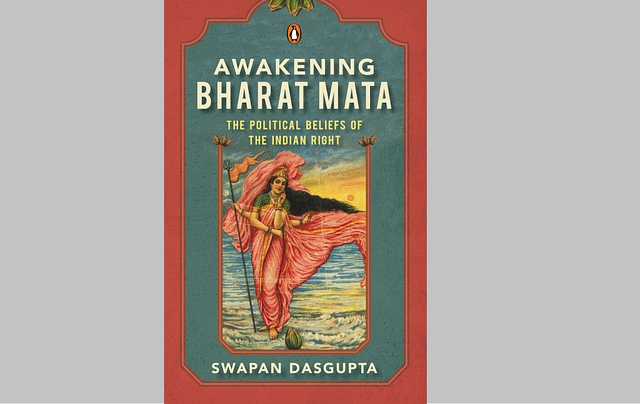

Awakening Bharat Mata: The Political Beliefs of the Indian Right. Swapan Dasgupta. Penguin Viking. 440 pages. Rs 420.

On 11 January 2019, the BJP formally launched its campaign to secure re-election of the Narendra Modi government. Speaking at the National Council convention to party cadres gathered from all parts of India, BJP president Amit Shah said the election of the Modi government in 2014 was a landmark in the history of independent India and it was crucial the gains be defended. The party, he said, had won important battles but there was no room for complacency: ‘2019 will be a decisive contest like the third battle of Panipat. The Marathas had won over 131 battles but lost in Panipat against the forces of Ahmad Shah Abdali. The Maratha defeat led to 200 years of colonial slavery.’

The historical analogy was telling. In the eyes of Hindu nationalists, the war to regain national sovereignty that had been launched with Shivaji’s rebellion against Mughal rule, did not culminate in the achievement of Independence in 1947, though that was an important step. India, they believed, would reach fulfilment and realize its manifest destiny once nationhood was recrafted to reflect its larger Hindu ethos.

This belief dated back to the early nationalists groping to imagine a post-colonial vision of India. In the late nineteenth century, the Bengali writer Bhudeb Mukhopadhyay penned a novel Swapnalabdha Bharater Itihas (A History of India as Revealed in a Dream). He visualized a Maratha victory in the third battle of Panipat against the Afghan invaders. For him, this victory was a decisive might-have-been moment of history and he envisaged a prosperous, united India, ruled by a wise Hindu monarch. The kingdom was the epitome of enlightened Hindu virtues — the rule of dharma that incorporated Western science and technology.

The evolution of a sovereign India that blended material progress with a strong sense of cultural rootedness was at the heart of the conservative Hindu nationalist project from the 1930s, when the end of British rule seemed imminent. Japan, quite predictably, was a major source of inspiration, as were some of the princely states such as Baroda and Mysore. The problem lay in nurturing a political vehicle that would make this transformation possible, a vehicle that was led by enlightened souls and relatively insulated from the distortions of mass politics. At the first Round Table Conference in London in 1930, the Maharaja of Rewa expressed his dismay that ‘in a country whose ways of life are so dominated by custom and tradition, there should be no political party which calls itself Conservative.’ He expressed the hope that as British rule was eased out, ‘a strong party of experienced and responsible politicians will emerge, which will call itself the Conservative Party’.

The hope was to remain unfulfilled for another five decades. The advent of Mahatma Gandhi as the undisputed leader of the freedom movement after 1920 put both Hindu nationalism and conservative politics in the shade. This is not to suggest that the ideas that were prominent in the earlier phases of nationalism were completely eclipsed. Far from it.

When he gave his call to achieve Swaraj in one year by boycotting all government institutions, Gandhi seemed the great deliverer that many Indians hoped would lift India from bondage, humiliation and despondency. His mass appeal was phenomenal, and he was cast in the role of a traditional guru and a saint, attributes that appealed particularly to rural folk whose involvement in the Congress had hitherto been nominal. Gandhi’s celebration of the Indian village and the village community, his partiality for indigenous medicine and his message of Ram Rajya appealed to a large body of traditionalists—particularly in Middle India — who had been less touched by the prevalence of Western ideas and lifestyles in the three presidencies.

However, just as Gandhi won mass adulation, he was viewed with some suspicion by many of those who had played a role in nurturing national consciousness in the earlier part of the century. Even those who accepted his leadership on account of his connect with ordinary people, Gandhi’s ideas were treated with considerable scepticism.

The doubts were broadly on account of three factors.

First, there was his steadfast refusal to accept technology — an aspect of modernity that enamoured Indians in search of national resurgence. Gandhi’s rejection of modern medicine, in particular, struck even his devoted followers as eccentric. Subhas Bose, who gave up a career in the Indian Civil Service to join his political mentor Chittaranjan Das in the movement for Swaraj in a year, could, for example, never quite understand why Gandhi elevated the medieval absurdity of the charkha into a modern panacea.

Secondly, his fanatical disavowal of violence directed against the enemy seemed bizarre to those inspired by the Italian Risorgimento and the daring deeds of the Fenians in Ireland, not to mention an underlying justification of violence for a just cause, particularly the restoration of dharma, in the Bhagavadgita. Whereas Gandhi viewed non-violence as evidence of great moral strength, his political detractors saw it as cowardice. The followers of Lokmanya Tilak, in particular, pitted themselves against Gandhi and their estrangement from the Congress was to become permanent.

One of Gandhi’s great political experiments in 1921 was to link the Congress’s movement for Swaraj with the Muslim agitation for the restoration of the Caliphate in Turkey. In tactical terms, this was a master stroke. For the first time since the uprising of 1857, British rule was confronted with significant opposition from both Hindus and Muslims. This combination made the movement particularly potent in towns and cities and neutralized to some extent Gandhi’s image as a Hindu leader. With his experiences in South Africa to guide him, Gandhi probably realized that the overwhelmingly Hindu ethos of the earlier swadeshi movement had left India’s largest religious minority cold. He sought to overcome this by calling for a multifaith patriotism, which left each religious community free to do their own thing. Addressing the question of Hindu-Muslim unity in 1920, Gandhi wrote:

I hold it to be utterly impossible for Hindus and Mahomedans to inter-marry and yet retain intact each other’s religion. And the true beauty of Hindu-Mahomedan Unity lies in each remaining true to his own religion and yet being true to each other… What then does the Hindu-Mahomedan Unity consist in and how can it be best promoted? The answer is simple. It consists in our having a common purpose, a common goal and common sorrows.

Confronted with the question of inter-dining, Gandhi suggested that stressing its importance was ‘a superstition borrowed from the West. Eating is a process just as vital as the other sanitary necessities of life. And if mankind had not, much to its harm, made of eating a fetish and indulgence we would have performed the operation of eating in private even as one performs the other necessary functions of life in private…’

Critics of Congress’s alliance with the Khilafat movement felt that Gandhi went a step too far in trying to accommodate the Muslim community. Historian R.C. Majumdar concluded that ‘there seems to be no doubt whatsoever that when he launched the Non-Cooperation movement on 1 August 1920, the Khilafat wrongs were the single issue which determined his action; the Punjab atrocities and the winning of swaraj were subordinate issues which were gradually tacked on to the main issue of Khilafat, at a later date and as an after-thought’.

Unfortunately for Gandhi, his gesture was never fully reciprocated by the Khilafat leadership. The Ali brothers saw the understanding with Gandhi as purely tactical — even on the question of the Mahatma’s pet theme of non-violence — and they were unconcerned with the idea of a common nationalism. In a speech in Broach, Gujarat, the Khilafat leader Mohammed Ali said that while at present they would keep the sword in its sheath, ‘we must reserve the right to take up arms against the enemies of Islam’. On another occasion, he made the astonishing assertion that if the Emir of Afghanistan chose to invade India, it was the duty of Indian Muslims to support him. In 1925, much after the Congress–Khilafat alliance broke down and Hindu–Muslim relations nosedived, Ali couldn’t conceal his distaste for Hindus. ‘However pure Gandhi’s character may be,’ he said, ‘he must appear to me from the point of view of religion inferior to any Mussalman, even though he be without character.’ He repeated this assertion of Muslim superiority later by saying that ‘according to my religion and creed, I hold an adulterous and a fallen Mussalman to be better than Mr Gandhi’.

The Non-Cooperation–Khilafat movement was the last time that a serious attempt was made to overcome sectarian divisions and forge a common nationality on the unity-in-action principle. As communal relations between Hindus and Muslims deteriorated and rioting became a recurrent feature of public life in many parts of India, the space for Hindu nationalism reopened.