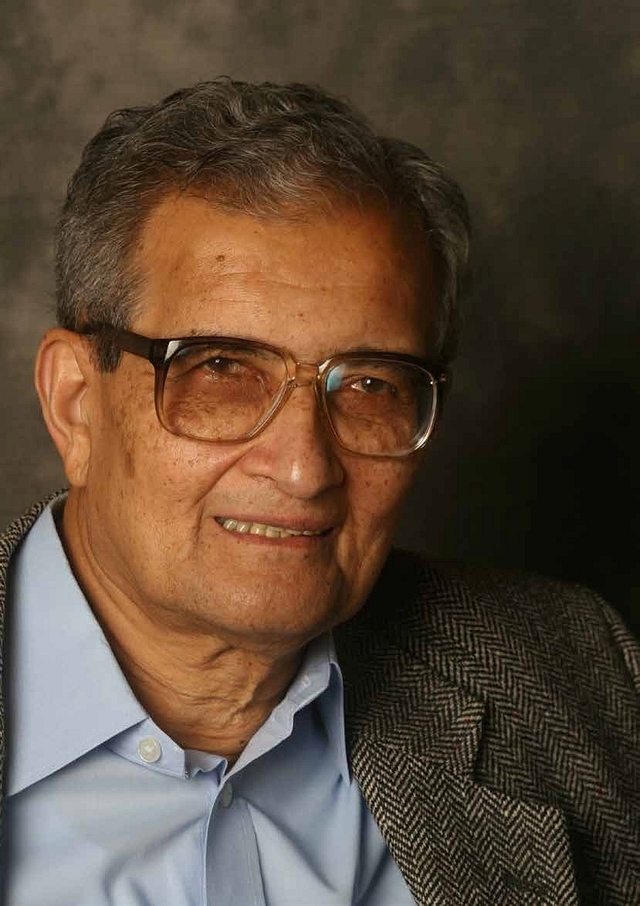

Why Amartya Sen Is Wrong

It is necessary for an intellectual of Sen’s standing to help India, but he can help only if he is willing to illuminate his discussions with his intelligence, not with his prejudices.

Amartya sen is brilliant. About that fact, there is no doubt at all. He is a genius, a scholar and he writes and speaks with superb aplomb. But just because the Swedes have recognized him (after which of course, the Bharat Sarkar duly handed him a Bharat Ratna!), and just because affluent leftists who live in Boston and subscribe to The New York Times admire Sen, it does not follow that he is always right. In fact, sometimes he can be and is dangerously wrong. Dangerous because people end up listening to him and doing foolish things.

He starts off his book on justice (The Idea of Justice, 2009), with a description of a hypothetical situation. There is a violin. And there are three children. One child made the violin; one child plays the violin very well; and one poor child has never had any toys. The ethical quandary: which child should get the violin? How best can the interests of justice and ethics be served?

The doctrine of property rights would suggest that the child who made the violin should get ownership rights. An aesthetically sensitive person would argue that the child who plays the violin best deserves it. The rest of us can get to listen to some great music. The total quantum of joy in the world would be increased, not just for the child, but for hundreds of listeners. Bleeding hearts would argue that the interests of equity and justice demand that the poor, deprived child who has never known the happiness of playing with toys is the obvious candidate for the violin. How can it be otherwise?

The rest of the book is a long meditative essay on this quandary and on related ideas of justice and ethics. It is a fascinating book by any standards.

But of course, the whole quandary is a phony one. Even Sen’s dim-witted undergraduate students should be able to figure out that if you violate property rights and take away the violin from the producer, no new violins will ever get produced. The gifted or the poor child will end up having the last violin on the planet. The producer child and his imitators will get the message clearly and bluntly: there are aesthetes and bleeding hearts out there who will expropriate the proceeds of my labour and my talent (to produce) and give it away to others who they consider more “deserving”. Why should I bother to make any more violins?

If we wish to ensure that there is a continuous supply of violins out there, it is blindingly obvious that the producer child has to be the owner. Incidentally, there is no reason to believe that the producer child will not share it with the others as long as the exchange transaction is seen as fair by all.

The talented child could offer to buy or lease the violin. If the talented child has no money, he or she can enter into a contract assigning part of future concert profits and recording rights to the producer. This is in fact a very likely denouement.

What about the poor child who does not have very bright prospects of earnings from concerts or recordings? This is where the cookie crumbles, according to the idiots of the leftist persuasion. But then, leftists hate the magic of financial markets. If only they knew that financial markets can in fact lend to the poor child against the expected cash flows from future earnings, then they would understand that even the deprived child has some hope, even if limited, of playing with the violin toy.

Our new government, which Sen disapproved of, has in fact started a massive national exercise, not to expropriate and give away violins to the poor child, but to get the poor child and its parents to open bank accounts and begin the process of accessing financial inclusion. In his numerous interviews to newspapers and TV channels, Sen does not even mention this potentially revolutionary move that might over time address the endowment constraints of the poor.

But then Sen has ideological disdain for pragmatic welfare measures that are pushed by admirers of the late Shyama Prasad Mukherjee. Foolish measures backed by the late Comrade Jyoti Basu or a leftist Allahabad Pandit family invariably receive a much more sympathetic consideration from the erudite Sen.

And financial inclusion, let me assure you, Dear Reader, is not a theoretical matter. I have personally promoted a finance company which lends every month to several hundred borrowers who do not have the fabled Bureau Ratings from agencies like Cibil. We make the loans using judgmental scores. Guess what, even though it is early days, we have very few non-performing assets and some 90 per cent of these borrowers actually obtain Agency Ratings in less than 12 months, implying that over time, they will access financial markets at lower interest rates.

Financial inclusion may in the next decade become the singlemost important anti-poverty and wealth-enhancing factor in our country. But then left wing UN experts (experts at what, I wonder?) do not have financial inclusion in their Human Development Indicators. In Kerala (Sen’s favourite state), financial inclusion is achieved by having the maximum penetration of gold retailers and gold lenders. Ergo: no kudos from Sen for any party or government that promotes financial inclusion.

The fundamental problem with the entitlements-based redistribution that people like Sen directly or indirectly endorse and which the previous UPA government vociferously supported, is that it is based on a phony foundation similar to that of depriving the producer child of the violin. The previous government told the citizens of India that they need not have any agency, they need do nothing—they just had lots of Rights—Rights to Education, Food, Health and much else. They could sit back. The government would do everything for them.

This might even be a tad credible if India were a wealthy country. But to give people unrealistic hopes that we can have Scandinavian welfare systems while the substructure of our economy resembles Zimbabwe, is nothing short of a cruel joke. The best way to improve the scale and quality of our education is to give School Choice Vouchers to parents. They would have agency. They would choose the school that their children went to. Instead, we have passed an obtuse law called the Right to Education Act which insists that private schools have libraries, laboratories, football fields and a great student-teacher ratio, while exempting government and minority schools from these restrictions.

Most teacher in government schools send their own children to private schools. These unionized teachers, according to the data supplied by Sen’s own NGO, do not turn up to teach and are particularly keen to be absent from schools where poor and Dalit students are present in large numbers. Sen is at best mild in his criticism of these unionized aristocrats, paid much more than private school teachers for not coming in to work. He keeps arguing for increasing the government’s Education Budget.

I wonder if he realizes the comical consequences of doubling the number of unionized government schoolteachers who do not teach. Will the children of India benefit?

On his recent trip to India, Sen was very critical of the fact that the new government has appointed some of its favourites to the defunct Akademies and Councils set up by its predecessors. I wonder what Sen was doing when the venerable Nurul Hassan systematically appointed shady mediocre leftists and communist fellow-travelers to a variety of institutions set up with the sole purpose of providing sinecures to these folks at the expense of the groaning Indian tax-payer. Professor Sen, democratic politics is about patronage. As a resident of Boston, you should know this.

What is the big deal if some quaint Hindutvic types get some quango (quasi-autonomous non-governmental organization) appointments? After all, they supported the winners in the recent elections. The friends of the losers are still around in large numbers at JNU and some might even be around at Nalanda University. Come, come, Professor. Be charitable. What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander—or so it should be!

Besides, I don’t think we need worry. Bodies like the History and Culture Councils of India, all of which have long and absurd names, have been pathetic under the earlier leftist dispensation. It is unlikely that they will do much now or in the future. As for the so-called terrible IIM Bill, I trust you are aware that the present government is putting out what its predecessor had in mind. It is the ultimate revenge of the Indian bureaucracy which wishes to strangle more and more nooks and crannies of unstrangled (is that a correct word?) India. Let us hope we can persuade the new government to put the Bill in cold storage.

Sen has raised concerns on ghar wapasi and church-burnings. Clearly, he subscribes to The New York Times which might as well change its name to Pravda or Izvestia. Professor, how come you have not talked about the assault on Roman Catholic nuns which I believe was vociferously discussed in Massachusetts? Perhaps you did not want to draw attention to the fact that the accused in that case turned out to be a common criminal—a Bangladeshi Muslim, probably in India illegally. While the West Bengal police is not known for its efficiency, you can at least be sure that this is not a sinister Hindutvic NDA plot as that unhappy state is ruled by a robustly secular non-bhadralok lady.

It is necessary for an intellectual of Sen’s standing to help India, given that he is so proud of having retained an Indian passport, apparently unlike some of his churlish critics. But he can help only if he is willing to illuminate his discussions with his enormous intelligence, not with his prejudices. After all, even a nobody like me has been positive about the MNREGA because it is an imaginative way to tap into the energies of our poor; it is not a dole or an entitlement and it might create some useful assets. Of course, like everything else in India, the challenge is in the implementation.

Sen has to embrace sensible initiatives of this government—initiatives like financial inclusion. He has to concede that increasing government spending in education or health is not an answer when the government delivery systems are broke, dysfunctional, wasteful and tyrannical. He needs to engage with options like School Vouchers which bypass the government delivery systems, and give credit to the fact that after decades, Indian citizens, particularly the poor, are being treated as agents, rather than as objects of pity and clientilism by pompous leftists.

And above all, he needs to give us ideas as to how to help the child who made the violin in the first place to make more violins and how to help the other two children rent or buy the violins.

If he engages with us on this basis, of course he may end up upsetting his admirers at JNU. But Professor, I submit that this is a risk worth taking. The dialogue will be more productive and the outcomes more useful.

The author is the former CEO of MphasiS, and was head of Citibank’s Global Technology Division. He is currently the Executive Chairman of Value and Budget Housing Corporation (VBHC), an affordable housing venture. Rao is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Swarajya.

This article was published in the August 2015 issue of Swarajya.