Jain Monk And The Media: Why The Incorrect Framing Of Debates Is Problematic

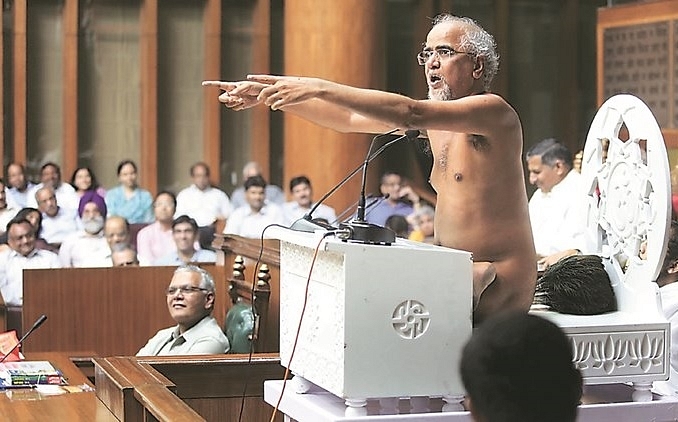

TV debates over the issue of a Jain monk addressing the Haryana Assembly in the nude were framed incorrectly from the beginning.

This is standard practice in media debates, which often feature incorrect premises, rambling and shifting goalposts.

Indian TV debates have a surreal character about them. They are about discussing or evading issues based on the anchor’s predilections rather than an open-ended search for differing viewpoints that can help people decide for themselves which argument makes the most sense to them. More often than not, the anchor frames the subject in order to maximise eyeballs, which results in the generation of more heat than light. If any light is actually shed in any debate, it is often an accident or an unexpected side-effect.

A debate framed wrongly obviously goes nowhere, or to the wrong places. So, whenever new insights come to light during the course of a debate, the anchor brings the focus back to the original frame. In fact, whenever anchors discover that their frame may have been wrong altogether, they shift their focus to avoid embarrassment to themselves.

This is what happened in yesterday’s (29 August) debate on the Jain monk who addressed the Haryana Assembly in the nude. For Digambar Jain monks, not wearing clothes is central to their faith. That the monk’s views on women were outdated was beside the point, but this came in only when they discovered that their main question was heading nowhere.

Most anchors framed the question along these lines: should a secular country call religious leaders to address legislatures? Missing in action was Arnab Goswami, who went off chasing Mandir Politics in Uttar Pradesh, obviously because his employers (The Times Group) are Jains.

The first and obvious point to make about how the debate was framed is simple: how does asking someone to address a legislature become antithetical to secularism? Does secularism mean not listening to persons of religion? States, legislatures and governments are free to listen to whoever they want to, and the mere fact that they asked a religious head to give them a talk does not mean secularism was abandoned. It does not even mean they have to listen to the advice given to them by a religious leader. The US Congress regularly asks priests from various faiths to offer prayers, and this does not make the US a non-secular nation.

The second point should have been even more obvious: Indian secularism does not necessitate a separation of the temple, church or mosque and the state. In fact, the Indian idea of secularism does not fit the European or American definition of the term, which is about separating church from state. It is about either being equidistant from all faiths, or showing equal respect to all of them, or granting equal favours. It is about panth nirpekshata – being neutral to any faith or denomination.

In practice, the “secular” Indian state is intensely involved in religious issues and activities, from subsidising the Haj to even running temples through state legislation. Some judges quote from the Qur’an to make justice available to Muslims under the Indian Constitution, and others question aspects of Hindu faith to deny them their religious right to worship a celibate deity by keeping some categories of women out.

Belief in secularism should not require a minister in the Government of India (read Sushma Swaraj) to attend a purely Catholic religious event – the canonisation of Mother Teresa – in the Vatican. But she still plans to do so. Indian laws are frequently tweaked to cater to minority religious whims, as the exclusion of minority schools from the ambit of the Right to Education Act proves.

So anyone who thinks that Indian secularism is about separating the religious from the temporal is dead wrong. You can argue that this is where we need to go, but that is not what Indian secularism is about in the present.

When the framing of the Jain monk issue failed to cut much ice, the anchors came armed to question the content of his message: his views on women were misogynistic.

The answer is, yes, his views on women were outdated and archaic, as is the case with all religions.

We tend to forget that almost all extant religions were created by men – and men only – and against the backdrop of patriarchy. The result is that most religious teachings are patriarchal in character. The rise of the Abrahamic religions made religion even more patriarchal, as they demolished pagan and animistic religions in their growth surge. While Christianity managed to find some space for mother worship, as it had to compete with mother cults, Islam simply does not have space for even such symbolic concessions. Religious hierarchies in almost any religion (barring probably the Brahmakumaris) are dominated by men, including the Catholic and Protestant Churches, not to speak of the ulema and the priests in Islam and Hinduism.

So a degree of anti-women sentiment exists in all religions, and the Jain monk’s views are no surprise. The only debate worth having on misogyny is whether some religions are less misogynistic than others.

Wrong premises, the incorrect framing of debates and shifting goalposts are the norm in Indian TV media debates. What a pity.